Natives

When did Native Americans inhabit Weirs Beach?

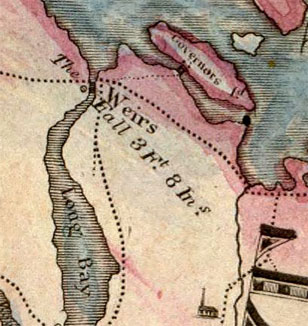

Before the 1829 Lakeport dam raised the Lake level, the Weirs Channel was actually a short river – there was a 3 foot, 8 inch drop from the Lake to Paugus Bay! Detail from an 1816 map. The Indian fish weirs were built just upstream of the falls, where the channel was quite shallow, from two to five feet in depth.

The Village

Weirs Beach has been habitated for thousands of years. A 1976-1977 archeological excavation at the beach, led by Charles Bolian, a Professor of Anthropology at the University of New Hampshire, found that Native Americans used the area as a summer camp for hunting and fishing as long ago as 8000 B.C! In 1931, the first scientific look at the area, the Merrimack Archaeological Survey by Warren Moorehead, had estimated the campsite population at over 400 people. The Aquedoctan archeological site at the beach was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.

The campsite extended in a long arc. It started at Doe Point in the Methodist campground, ran along the lake shoreline to the Weirs Channel, then along the western shoreline of Paugus Bay as far as Moultons Cove. There was considerable fairly level space all along the shore for the summer wigwams. Before the original Lakeport dam was built in 1781, the level of the Lake was roughly 5′-12′ lower than it is today, so much of the original campsite is now under water!

Around 1000 B.C. the inhabitants began living there in a year-round village rather than just camping there during the summer. The location provided a source of year-round water, as the Channel does not freeze in the winter, and it was well buffered from winter winds by the mass of Brickyard Mountain. The largest level area was in the vicinity of what is now the Weirs Beach Drive-In. This was the center of the village, where the longhouse would have been located, protected by a palisade (a high wall of upright logs) for defense against hostile tribes, especially the aggressive Ossipees to the north, or the Penacooks to the south.

The cornfields, essential to year-round habitation, were spread up the hill towards Meredith. The large tracts of land were cleared by burning in the late fall, during the dryest conditions. To support a village of 400 people, about 80-100 acres of corn would need to be planted in the springtime, in order to produce the eight or so bushels of corn that were needed for each person in the village every year. Permanent habitation for a village of 400 would require 330-580 acres of cropland in order to allow for enough land to be continuously cultivated, while other cropland would lie fallow and resting, so the soil could replenish itself and become fertile again. This latter rejuvenation process could take as long as 25-50 years. (see A Time Before New Hampshire: The Story of a Land and Native Peoples by Michael J. Caduto, pgs 179-180, 191.)

Much later, the cornfields would become the farms of the early white settlers, who found them still devoid of the largest trees. In the 1800s, the Blaisdell Farm property spread over 400 acres from the top of Tower Hill to Brickyard Mountain, so there was certainly enough room at the Weirs for the Indians’ cornfields. A mortar for grinding corn was preserved at the Weirs Beach waterfront until 1991 when it was inadvertently destroyed.

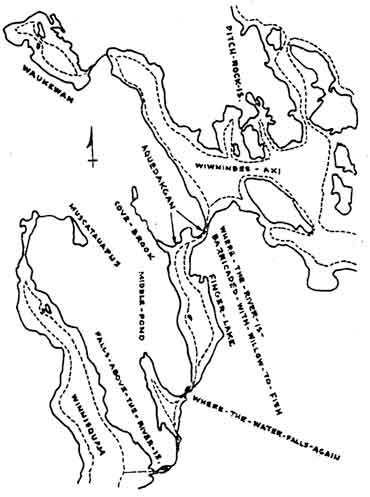

The native tribe of Winnepiseogees shared their name with the Lake, belonged to the Pennacook confederacy, and were ethnically Western Abenakis, who were part of the Algonquian peoples. They called their village Agua-dak-‘gan (Aquedoctan), meaning “a landing for portage” (agua-dak, a landing, and ‘gan, short for wnigan, portage). (The older, probably incorrect interpretation of the name was that Aquedoctan meant “a place of good fishing”. A newer interpretation of the name spells it as Adelahigan and the meaning as “barring-the-way-thing”.) However, according to Frederick Matthew Wiseman, a Native American and author of “The Voice of the Dawn: An Auto-history of the Abenaki Nation”, the village was actually named Nonegonnikon Wiwinebesaki, meaning “a village at the lake in the vicinity of which there are other lakes and ponds”, from wiwini, (around, in the vicinity), nebes (lakes or ponds), and aki (region or territory) – literally, Lakes Region Village. For more about the meaning of the name of the Lake, click here.

Bolian discovered a hearth at the very bottom of his dig that was carbon dated as “9,615 +/-225 years B.P.” (before present). Bolian has been criticized for never publishing the final results of his excavations. Bolian only published a preliminary report and a brief follow-up analysis. This early date is considered by archeologists as “Late Paleo-Indian” bordering on the “Early Archaic” period of cultural development, when the native culture was one of small family groups engaged in a semi-nomadic lifestyle – hunting, fishing, and gathering at one place, then moving on when the fish runs were over, and the wild game, edible plant life, and firewood in the area were depleted. This was the summer use of Weirs Beach during the 8000 B.C. – 1000 B.C. time period.

The “Woodland” period began in 1000 B.C. with the arrival of ceramics in the form of plainly-made pottery vessels. Decorative markings were not added until later. Horticulture, storage pits, and village life were the other main distinguishing features of the Woodland culture. Growing of corn crops began around 800 A.D. – 1000 A.D. Then, the introduction of deep storage pits lined with bark allowed food to keep for winter, making year-round village life possible. The Woodland period continued until the “Contact” period began in 1600 A.D.

In May, 2023, archeologist Nathaniel R. Kitchel led a dig at the beach consisting of 4 L-shaped pits. On April 6, 2024, Kitchel’s student assistant, Karlee Feinen, presented a report at the New Hampshire Archeological Society called Dirty Stratigraphy: The Stratigraphy of Weirs Beach. Five different layers, or strata, were found in the dig; the fourth layer, a black layer from 50-70 centimeters down, was where artifacts from both the “pre-historic” (before 1600) and historic (post-1600) periods were found. The artifacts were all mixed up, indicating that previous “earth-moving”, during dredging of the channel and construction of the parking lot, had permanently altered the site’s utility for archeological purposes.

Noticing the dramatic difference only a few feet can make in the appearance of the shoreline, one can only wonder what the Lake looked like before the Lakeport dam, when it was 5-12 feet lower! The map below, from the book “Algonquian New Hampshire”, gives an indication. Click here to see the Lake when it was very low in 2001.

The Weirs

For fishing, the villagers built a special type of fish trap, called a WEIR, (also known as an Ahquedakenash, click for more info) to capture the abundant migratory species – both fish (American shad) and eels (American eels). In the spring, both species migrated upriver on their 128 mile journey from the sea — first up the Merrimack River, then up the Winnipesaukee River, and finally through the Weirs Channel to Lake Winnipesaukee. In the fall, the migration route was reversed. In the spring, it was the fat, adult shad that were caught and kept. The spring eels would be in their immature, 2″ – 6″, elver stage, and let go. In the fall, it was the young, 3″ – 4″ shad that were let go, while the mature, silver eels, averaging about 1.5′ – 2′ long, were caught and consumed.

The WEIRS went into the channel to block the species from passing through, effectively trapping them. The original fishing WEIRS had been made of wooden fencing in the form of a “W”and stretched across the entire width of the channel. The lower two points of the “W” pointed downstream towards Paugus Bay and were utilized during the fall down-river migration. This diverted the species from the middle of the channel towards the riverbanks, allowing the natives to more easily scoop the fish from either side of the Weirs Channel. Historian Erastus P. Jewell, donator of a large collection of Indian relics to Laconia’s Gale library, wrote that the points of the “W” were “…left open a few feet for the water and fish to pass through. A short distance above the opening another fence was built in a half-circle, and into the spaces was placed wicker-work, made of small saplings, through which the water could easily flow, but fine enough to entrap fish of any considerable size.” During the spring, during the up-river migration, the upper point of the “W”, which pointed upstream towards the lake from the middle of the Weirs Channel, was used. The natives would paddle their canoes to the middle of the channel, load them up with fish, and deliver them to the squaws waiting on the riverbanks to split and smoke them.

Historian Solon B. Colby explained how the wooden fencing was made. “The Indians built temporary weirs of stakes and interwoven brush. Where the river bottom was too hard to drive a stake, the Indians would place two good sized rocks where needed, with an upright placed between them. When enough uprights or stakes had been properly placed, brush was interwoven with the uprights to make a fence which permitted the water to pass through but guided the fish to openings in the weirs and into the nets of the Indians. The brush remained in the Weirs Channel until the ice went out in the spring, taking the lightly-constructed fish weirs with it. New weirs were built during the last two weeks of May in preparation for the shad run which began about June 1st.”

Jewell adds, “When the white settlers came, the ‘Weirs’ were in a good state of preservation and were made use of by them. Fish wardens were appointed annually, whose duty it was to go two days each week to see that the fish were fairly distributed among the people assembled to wait for them. With the exception of the two days a week when the wardens were present, anyone could take fish from the traps. Frequently the early settlers would find the basket-like traps well filled with fine fish, and all our fathers had to do was to take out the helpless captives.”

Colby contradicts Jewell’s statement that the weirs were preserved. “When the early settlers came to Aquadoctan in 1765, seventy years after the Indians had left, the uprights and brush had long been gone, but many of the rocks which once braced the uprights could still be seen scattered along the channel bottom.” However, the early settlers soon built their own weirs. Colby notes that, “The banks of the Winnipesaukee River were occupied by early settlers in preference to the other localities because of the fishing facilities which that river afforded. The eels and shad for which the Winnipesaukee was once famous, were essential to the settlers as a means of subsistence until their crops came into bearing.”

“In the early days these fish were thought of sufficient importance that acts were passed by localities to preserve the fish. One of the preservation methods was to ban construction of weirs that were built from opposite sides of the river so as to span the whole stream, which would be damaging to those who built their weirs farther downstream. Wardens were employed to “…see that ye river is not encumbered by wares; and that one half the river be kept clear…on penalty of twenty shillings upon every man who shall build a ware more than half across.”

Between 1764 and 1820, the NH state legislature passed fourteen acts concerning fishing. There were limits on the days fish could be caught, limits on the size of seines (fishing nets), and regulations against obstructing the seasonal fish runs. But the fishing laws were routinely circumvented. Fish wardens were ignored, avoided, or bribed. The result was overfishing to some extent, but this hardly mattered compared to the dams that were soon built all along the riverways.

Warren Morehead, in his 1931 Merrimack Archaeological Survey, noted that the Weirs “…take its name from the very extensive fish traps maintained by the Indians at the outlet. Governor Endicott and his people heard of the importance of this center and visited the Indians. There are not wanting descriptions in our earliest records of fish taking at this spot, and doubtless many tons of dried fish were prepared by the Red Men for winter consumption. Some of the stones, which held in place the wooden weirs, may be observed even at the present time. It is sad to record that most of them were removed from their ancient resting place in order that a deeper channel might be utilized by speed boats. As there are more than forty miles of waterways available northwest of The Weirs bridge, and not much more than a mile below the bridge, it is not merely unfortunate but inexcusable that such vandalism should have occurred. Those ancient weirs deserved a better fate.”

A popular misconception was that the Indian Weirs were made of sturdy stone walls, and that their remains were still in evidence until the dredging of the Weirs Channel in the early 1950’s. Colby stated that the visible stones were remnants of an earlier wing dam built in the channel. The wing dam had been built like a stone wall, with stones gathered from the channel bottom. According to Colby, when the channel was dredged in 1833, the stones were “…erroneously described by journalists as the remains of an ancient Indian fish-weir.”

Colby’s reference to a wing dam is the starting point for an exploration of the several miller’s dams that were built in the Weirs Channel from circa 1798 until 1829. Click on the link for extensive info about the Weirs Channel miller’s dams and other early dams that were built downstream on the Winnipesaukee River in Lakeport and Laconia.

Artistic depiction of the stone Weirs.

The photo below shows remains of the Weirs. On the back of the photo, an unknown author wrote, “The low water shows some of these walls that look like small pens, which can be seen from the bridge today. Many different tribes of Indians went to the Weirs for their supply of fish. They had made a trap of stones in the channel to catch the fish in the form of the letter W. The lower points of the letter extended below the bridge, and the upper walls touched the shore some distance above towards the lake. The trap was built so high that the water did not often cover the stones. At the lower points there was an opening left, so the fish could easily run thru. Below these points, a half circle was made of small saplings thru which the water would run, but after the fish swam into these, they could not turn back. If there were not many fish in the traps, the Indians went out with long poles and branches of trees, beat the water in the lake, and drove the fish into the traps. The Indians dipped them out with their “Wiccopee” baskets, made out a tough bark that grew nearby. They then dried them for future use.” Click on the link for more info about the bark and an illustration of Ancient Aquedoctan.

Map of Abenaki tribes of New Hampshire. From “Indians of New Hampshire”, a booklet first published in 1965. Author and historian Eva Augusta Speare (1875-1972) was known as Plymouth’s “First Lady”. According to Speare, “English settlers estimated that New England was inhabited by 50,000 Indians, but New Hampshire probably did not have over 5000 Red-men…”

The Shad Run

The adult shad migration from the sea to the lake peaked during the first two weeks of June; while the young shad migration from the lake to the sea peaked during the late summer. Colby wrote,

“Our forefathers told marvelous stories about the abundance of fish in the Merrimack River and its two main branches, the Pemigewasset and the Winnipesaukee. The fish were fat, huge, and luscious, moving upstream in such numbers in spring or spawning time as to blacken the river with their backs. While the shad and salmon swam together up the Merrimack river, they parted company at the junction of the Pemigewasset and Winnipesaukee rivers in Franklin. The salmon, delighting in cold, swift water, swam up the Pemigewasset. The shad, much larger fish that sought large lakes for spawning where the water was warm and abundant, swam up the Winnipesaukee.”

“The shad as a rule reached Pawtucket Falls at Lowell about the first week in May; by May fifteenth they were at Amoskeag, and by the last week in May they could be found in the Winnipesaukee River. At this time the water would be literally crowded with shad weighing from three to five pounds. In some sections of the Winnipesaukee River, natural obstructions made it unnecessary to set up weirs. Certain pools were so full of shad that one Indian with a dipnet or spear could take several hundred pounds in one day.”

“The old shad returned to the sea in August in an emaciated condition due to their having fasted during their spawning activities. If any were found in eel-pots they were always liberated with the reasonable assurance that they would be in better condition when they returned the following year. The young shad started their migration to the ocean in September at which time they were only three or four inches in length.” (Unlike salmon, who die right after spawning, American Shad have several reproductive cycles during their lifetime. Both young and old shad were let go in the fall as they would return fattened up the following spring.)

It is unknown exactly when the shad ended migrating to and from the lake, however, it is clear that the many dams on the Merrimack and Winnipesaukee rivers, as well as a multitude of canals and locks on the Merrimack, all built in the late 18th and 19th centuries, caused the migration to collapse. In 1789, an estimated 830,000 shad were caught in the Merrimack; but by 1888, the Merrimack catch was zero.

There were early attempts to solve the problem. In 1864, NH passed a bill requesting Massachusetts and other states to restore free passage of fish up the state’s rivers. This was followed by a NH bill in 1865 requiring fishways along the state’s major rivers, including the Merrimack, Pemigewasett, and Winnipesaukee. By 1867, all the New England states save RI had formed fish commissions to supervise the restoration of migrating fish to the region’s waterways. By 1868, on the Winnipesaukee River, the Franklin Falls Company, which owned the first four dams, and the Lake Company, which owned or controlled the remaining dams, had all complied with the 1865 NH act and built fish passageways at their dams. By 1868, fishways were also in place on the Merrimack at Lowell, Lawrence, and Manchester. The Merrimack fishways were rebuilt and improved in the 1870s. Along with restocking efforts, this resulted in a noticeable improvement in the salmon migration by 1878, with salmon returning to the upper reaches of the Merrimack and Pemigewasett for the first time in decades. It did not help the shad. Salmon are noted for their remarkable jumping ability, with some able to jump over waterfalls and rapids as high as eleven feet. While some progress had been made, it did not last. When the Sewall’s Falls dam in Concord was built in 1892-1895, it once again ended the salmon run.

The Lake Company

The Lowell and Lawrence mills in Massachusetts, recognizing that control of the Merrimack’s sources in New Hampshire was crucial to the water delivery system which powered their mills, joined forces in 1845 to buy rights to the waters of Lake Winnipesaukee, Newfound Lake, and Squam Lake. Their quiet and stealthy acquistion of water rights between 1845-1856 set off what was known as the Winnipesaukee Water War, which came to a head with an attack on the Lakeport Dam on September 28, 1859. The issue was the overall level of the lake, which even today can be a topic of disagreement. Either the water level was too high, flooding shoreline farmland, or it was too low, impeding navigation and log drives, and lowering water power to local mills.

Abbot Lawrence, for whom the city of Lawrence was named, started off by purchasing the Winnipisiogee Lake Cotton and Woolen Manufacturing Company in 1845. The company had been incorporated by Nathan Batchelder and Stephen C. Lyford in 1831 to run their two textile mills in Lakeport. The purchase gave Lawrence control of 250 acres of land, factory buildings, and water rights to the Lakeport dam. The company was quickly transformed from a limited local venture into a vastly larger enterprise focused on taking command of the entirety of the Lakes Region’s water resources. In 1846, the name of the company was changed to the innocuous-sounding Lake Company, and its capitalization was multiplied tenfold.

The company expanded its control of Lake Winnipesaukee and its 45,000 acres of water by signing numerous agreements with downstream users. The owners of the water rights at the Avery Dam sold them to the Lake Company in 1852 for $11,000. The company gained control of of Lake Winnisquam and its 4,200 acres when it signed agreements regarding the Pearson Dam (now the Lochmere Dam) in 1852 and 1853. This gave the company effective control of the Winnipesaukee River, one of the two main rivers combining to form the Merrimack.

The company next set its sights on the other main river, the Pemigewasett, which was fed by the Squam Lakes and Newfound Lake. It gained control of Squam Lake (6,700 acres) and Little Squam Lake (400 acres) by dredging the channel between the two lakes, and building a 150-foot dam at their combined outlet to the Squam River in 1848-1849, a dam that raised the level of the two lakes by several feet. It gained control of Newfound Lake (4,100 acres) by building a dam in Bristol in 1852. Rebuilt in 1858-1859, the Bristol dam was 8 feet high and raised Newfound Lake by the same amount, while the channel beneath the dam was lowered three feet.

Finally, the Company gained control of Lake Wentworth (3,000 acres), a feeder lake to Lake Winnipesaukee, in 1854, and built a dam at its outlet pond in 1856. In total, by 1856, the Company controlled 63,400 acres of surface water, about 100 square miles.

(Lake Wentworth flows into Crescent Lake, which flows into the Smith River, which flows into Mill Pond, which flows into Back Bay, which flows into Lake Winnipesaukee. The Lake Company dam was built at the outlet of Crescent Lake. There is a second dam between Mill Pond and Back Bay. The Cotton Valley Rail Trail crosses this second dam. Wolfeboro Falls is the section of Wolfeboro between the two dams.)

The Company’s swift and stunning total control of the Lakes Region’s water resources led to much antipathy and resentment towards the Company from many locals. Noted Weirs historian Edgar H. Wilcomb, on pages 15-18 of his 1923 booklet, “The Lakeport Cleft“, wrote a chapter titled “Beautiful But Damned”, where he condemns the Lake Company in no uncertain terms. Writes Wilcomb, “One of the most shameful public acts ever to be perpetrated in the State of New Hampshire was the conveyance of the rights of the people of the state to a foreign-owned corporation, whereby the waters of Lake Winnipesaukee are entirely controlled for the benefit of another state…Are we to be forever beholden to a flim-flam arrangement that was worked upon our unsophisticated ancestors by a gang of Massachusetts sharps?”

The Lake Company faced some minor setbacks when it lost at trial in three separate cases in 1872, 1873, and 1874. In the first case, the Company had to pay the town of Gilford for flooding town land above the Lakeport dam. In the second case, the Company had to pay Benjamin Holden, owner of a mill below the Lakeport dam, for failing to provide adequate water in the summer to his business. Finally, the Company lost to Lakeport magnate Benjamin J. Cole, for partially obstructing a short canal that led to Cole’s iron foundry and machine shop. However, the damages the Company paid were insignificant. Another setback occurred on May 20, 1877, when another attack on the Lakeport dam occurred, this time to enable a log run. Rather than fight it out in court with the loggers, the Company installed a log sluiceway at the dam.

On February 20, 1878, in reponse to a petition with 1,170 signatures, a state commission was formed to investigate the Company in order to find “…whether the Company had conducted its management and affairs as to greatly injure the business and prosperity of the residents of this State.” While the commission investigated, in order to forestall further attacks and lawsuits against the Company, the Lowell and Lawrence owners decided to invite the Amoskeag Company of Manchester, NH to purchase a third share of the venture. By including the Amoskeag Company as a one-third partner, the Company would no longer be perceived as exclusively a Massachusetts operation. In December, 1878, the Amoskeag Company agreed to join the Company, and its lawyers were directed to prepare the restructuring paperwork. Now, to fight the Company would be against NH manufacturing interests, as well as the ones in Mass.

In March, 1878, Charles Storrow, the long-time chief engineer for the Lawrence Mills, appeared before the commission. He testified, “All the improvements of the Lake Company upon all the tributaries of the Merrimack are available at every fall upon the 60 miles of that River from Franklin to the Southern boundary of the State. Upon those sixty miles are situated the largest and most important manufacturing establishments of New Hampshire, to whom these improvements are of least as great advantage as they are or can be to any beyond the limits of the State. The Company does not draw water out of the State, but draws it to run through the State.” Storrow portrayed the Company as public-minded in making the water flow more uniform. Its interest in managing the water was “identical with the whole manufacturing industry of the State of New Hampshire.”

In the spring of 1879, the commission published its final report. It found decidely in favor of the Company, saying that the Company had contributed substantially to the wealth and importance of the inhabitants of the state. It found that the manufacturing interests in the state had greatly benefited from “the holding of waters in these reservoirs for the dry season.” And, as far as navigation was concerned, the Company’s excavations at the Weirs Channel had improved it, by allowing steamships to pass from Paugus Bay into the Lake and back.

The “Water War” ended only a decade later. In the late 1800s, as manufacturing mills all along the Merrimack shifted rapidly from undependable water power, to reliable, coal-fed steam power, water power became less and less important. In 1889, the Lake Company sold their water rights to the Winnepiseogee Paper Company, owners of many of the mills in Franklin.

As textile and paper production moved to the South in the 1920s and 1930s, mills all along the Winnipesaukee River and the Merrimack failed, including the giant Amoskeag Mill in Manchester, once the largest textile manufacturer in the world, which closed in 1935. The remaining dams had all been converted from water power to the generation of electricity. The Federal Power Act of 1920, revised in 1935, imposed many regulations on dams, and made the combination of manufacturing operations and electrical power production particularly difficult. In 1943, NH’s largest electric utility, PSNH, took ownership of the Lakeport Dam. On March 31, 1958, the New Hampshire state government finally took control of the Lakes Region water flow, when ownership of the dam passed to the New Hampshire Water Resources Board. The board’s name was discontinued when it was merged into the NH-DES (Department of Environmental Services) in 1987.

In reality, the control of the lakes was never as advantageous to the Lowell and Lawrence mills as planned, nor did it disadvantage the local mills to the extent that was perceived by the local NH citizenry. Because the NH lakes were far away from the mills in Lowell and Lawrence (about 100 miles), it took several days for the water to arrive downstream. Meanwhile, the water from the mill ponds behind the two cities’ dams was always available immediately. The main improvement in water flow for the Lowell and Lawrence mills was in the dry season, between July and October. While it was not the intention of the Lake Company to improve the water power available in NH, its excavations and careful management of the water made the natural water flow more continuous and reliable. So while the Massachusetts mills benefited, so did the ones in New Hampshire. With higher average lake levels, navigation on the NH lakes was also improved. The only real losers were the farmers who found their lakeside farms partly submerged without compensation. But during the late 19th century, farming was a dying industry in NH anyways. The real estate bonanza of owning and developing lakeside property was not to come until nearly a century later.

Much of the above is drawn from chapters 4 and 8 of Nature Incorporated: Industrialization and the Waters of New England by Theodore Steinberg, published 1991, Cambridge University Press.

Modern Restoration Efforts

Even today, the Merrimack still supplies power to cities and industry, via five hydroelectric dams on the river, and almost 100 small power projects. The Anadromous Fish Conservation Act of 1965 led to a joint, multi-state and federal effort to restore migratory Merrimack fish such as shad. The Merrimack River Anadromous Fish Committee is comprised of the Massachusets Division of Marine Fisheries; the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife; the New Hampshire Department of Fish and Game; the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Marine Fisheries Service, and the US Forest Service.

The first two obstructions on the river are the Essex Dam in Lawrence, and the Pawtucket Dam in Lowell. While these two dams have had fish passages since the middle of the 19th century, they simply did not work. When the restoration effort began, in 1969, shad were brought by truck from below Lawrence and released above Lowell to continue their journey. The completion of modern fish lifts in 1982 (Essex) and 1986 (Pawtucket) has allowed shad to move naturally upstream as far as Manchester after more than a century’s absence. In 1989, the Amoskeag Dam in Manchester completed its modern fishways. To make their way past Manchester, upstream to the junction of the Winnipesaukee River and Pemigewasett River in Franklin, now seems possible.

On the Merrimack, the only remaining obstacles are the Hooksett Dam and the Garvin Falls Dam in Bow. (The Sewalls Falls Dam in Concord, now a public park, was breached on April 7, 1984, and is no longer an obstacle.) Downstream fish passageways were built at the Hookset and Garvin Falls dams in 1988. On May 18, 2007, PSNH received a new 40-year license from the FERC (the Federal Energy Regulatory Commision) for its 3 dams on the Merrimack. PSNH was required to build an upstream fish passageway at Hooksett after 9,500 shad passed Amoskeag Station, and an upstream passageway at Garvin Falls after 9,800 shad passed Hooksett. (Since 2018, the three dams have been owned by Central Rivers Power, also known as Patriot Hydro.) A fish count, dated 7/13/2011, showed that only 1,198 shad had made it past Pawtucket.

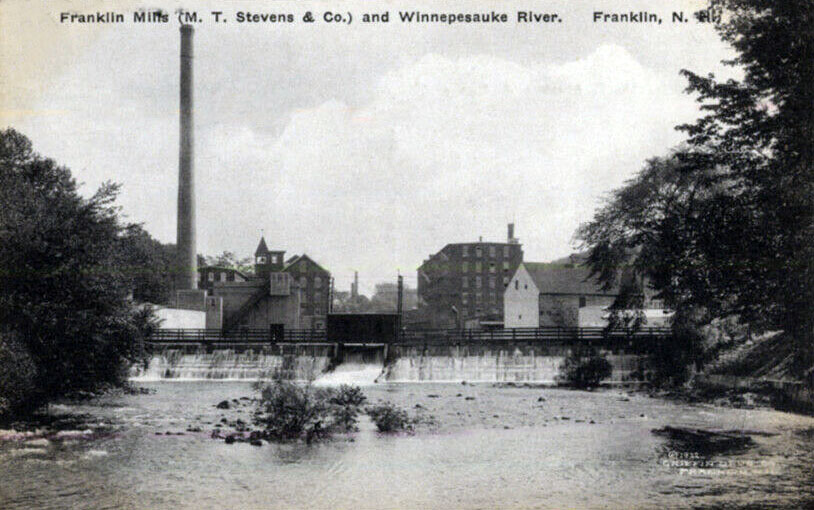

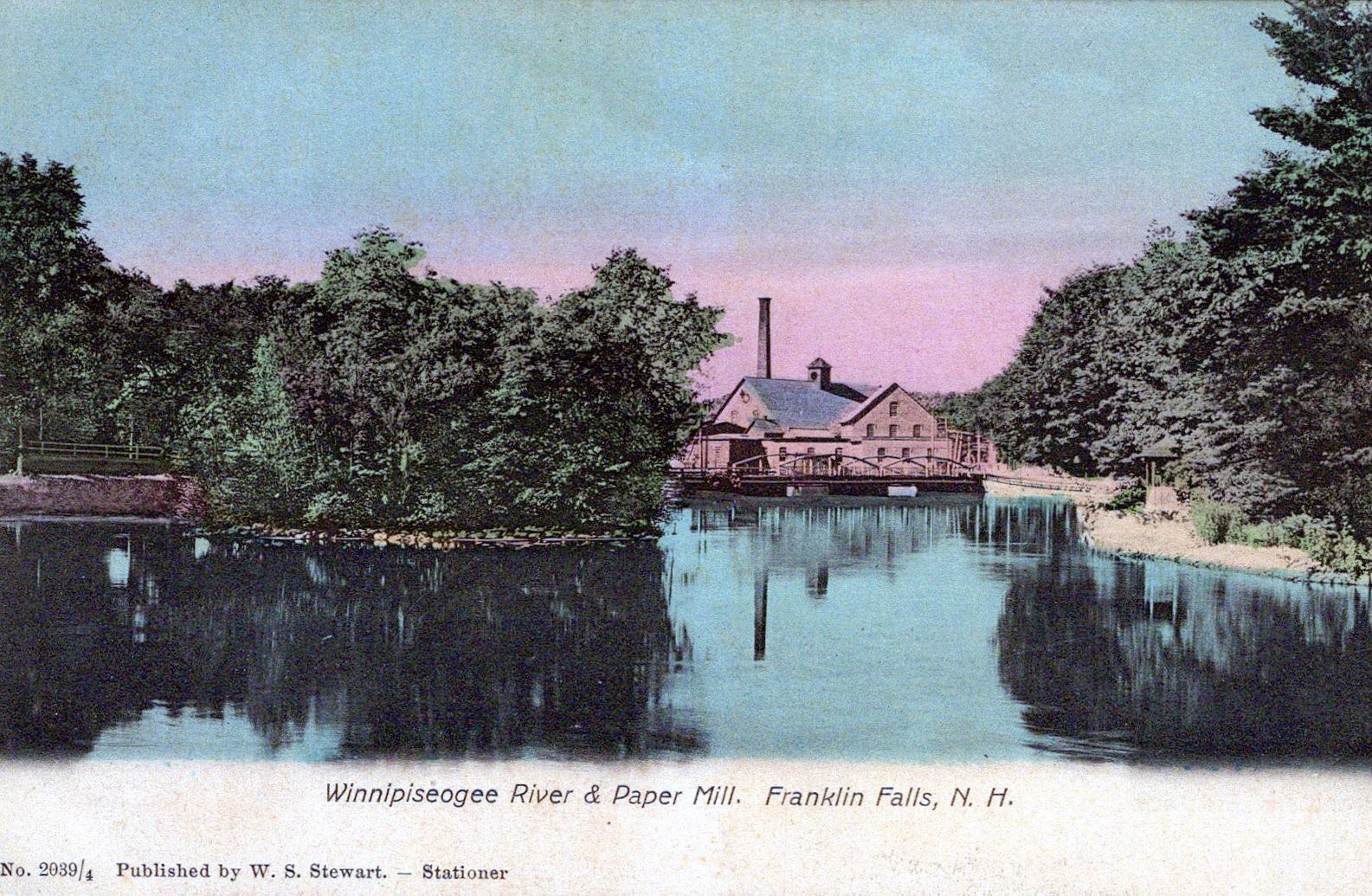

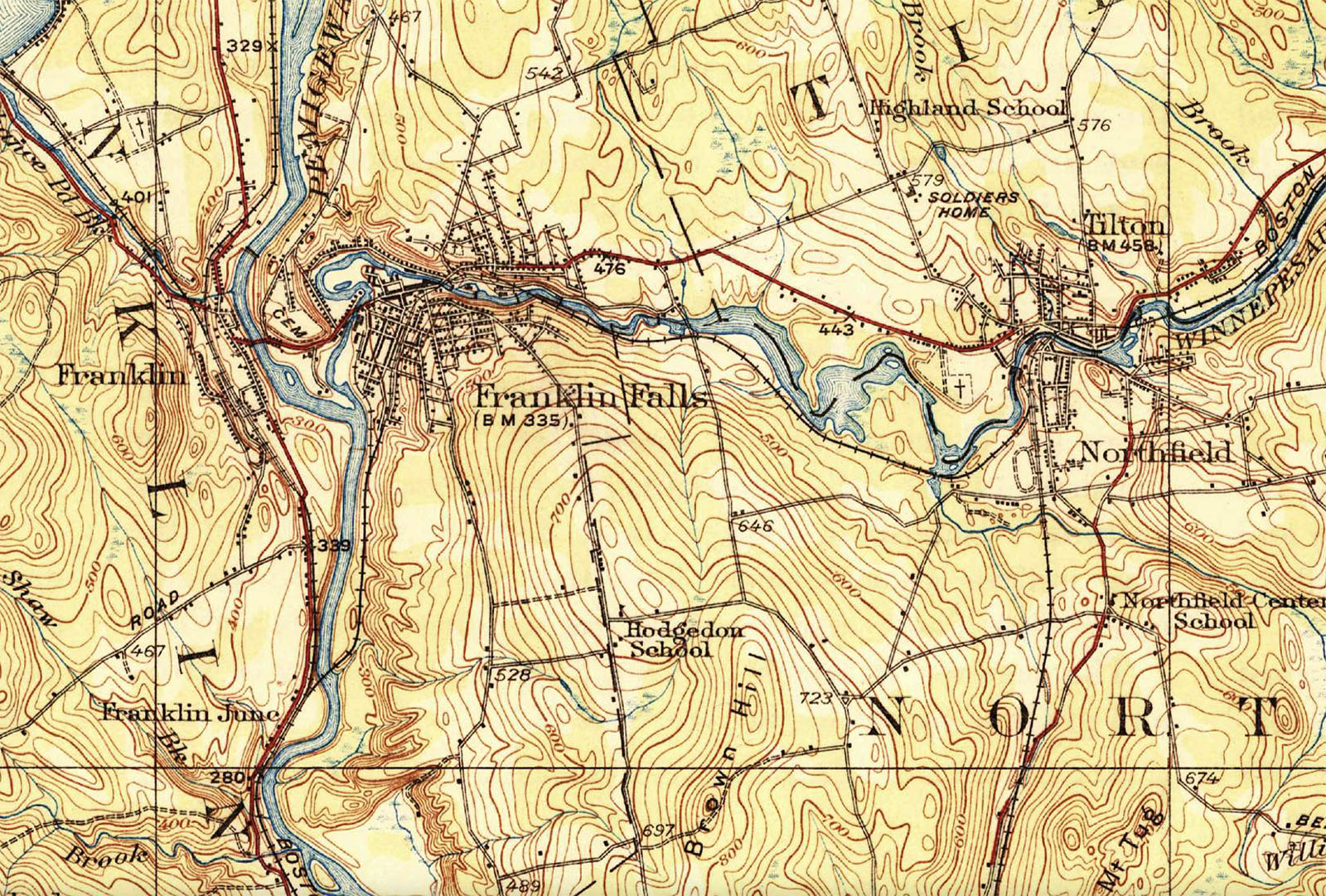

If the shad ever do make it to the head of the Merrimack, at the confluence of the Pemigewasett and Winnipesaukee rivers, there are six dams on the Winnipesaukee River that remain formidable obstacles to the shad making it all the way back to Lake Winnipesaukee. Going upstream from the confluence, the first dam is the River Bend power station in Franklin, part of the Stevens Mill Dam complex in Franklin. The second dam is the Bow Street power station in Franklin, also known as the Franklin Mills Dam* (see photo below). The remaining four upstream dams are the Clement Dam in Tilton, the Lochmere Dam in Belmont, the Avery Dam in Laconia, and the Lakeport Dam.

*The Franklin Mills dam should not be confused with the Franklin Falls dam on the Pemigewasett. The Eastman Falls dam in Franklin is also on the Pemi.

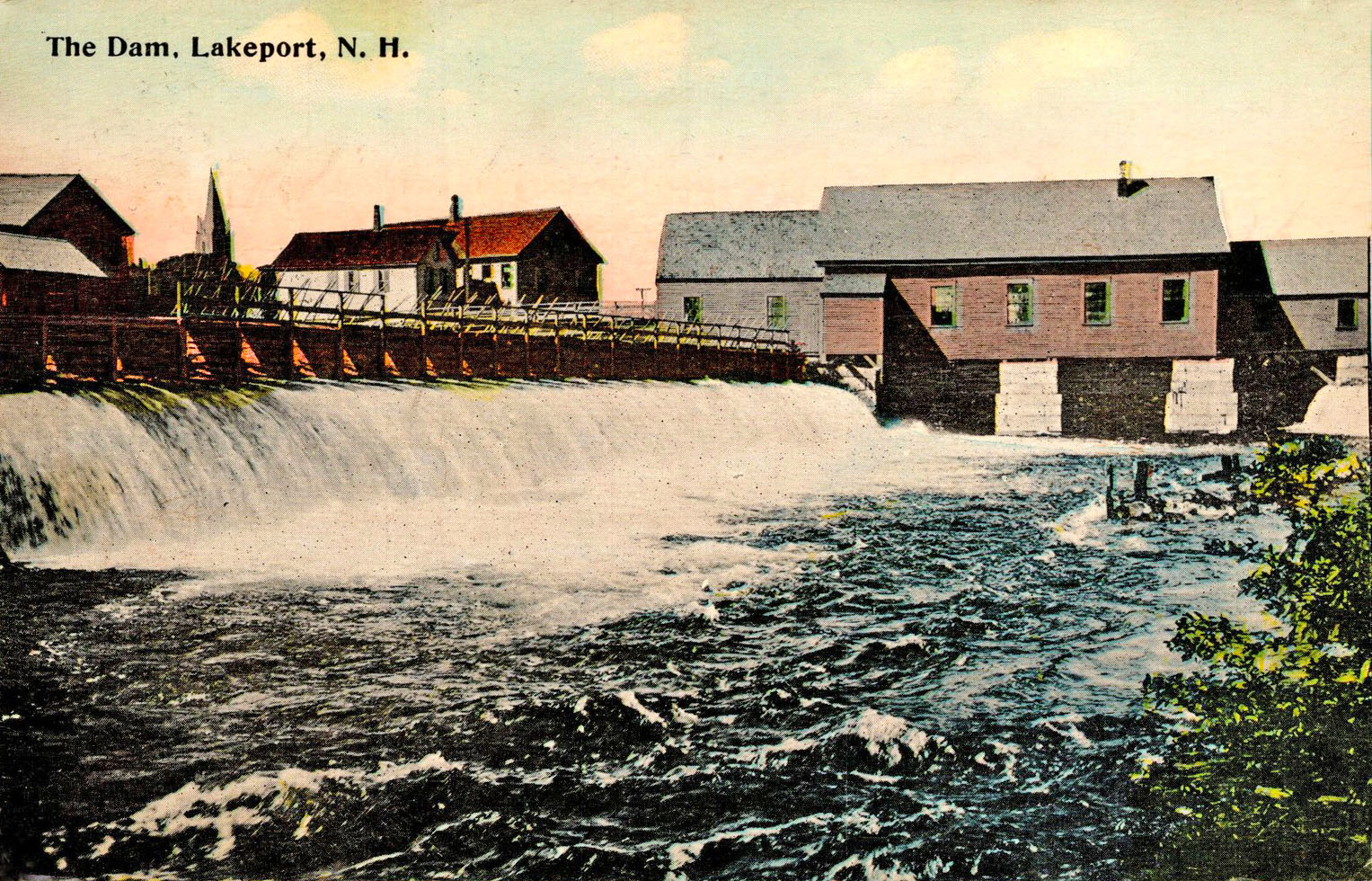

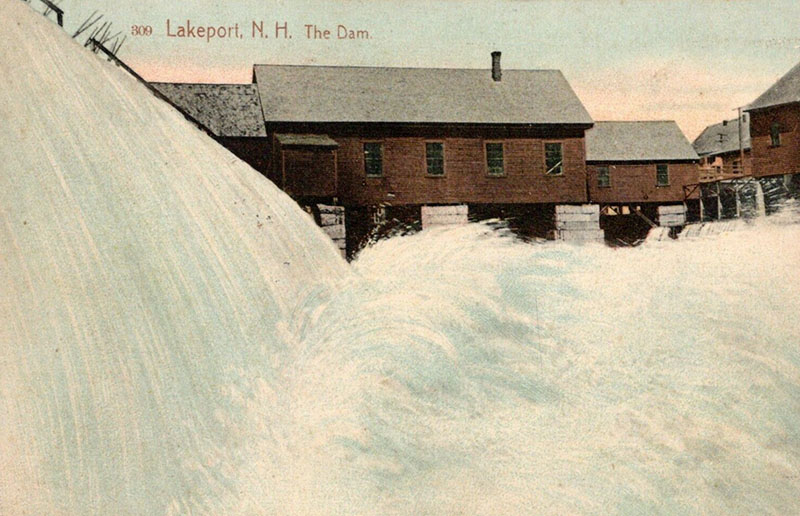

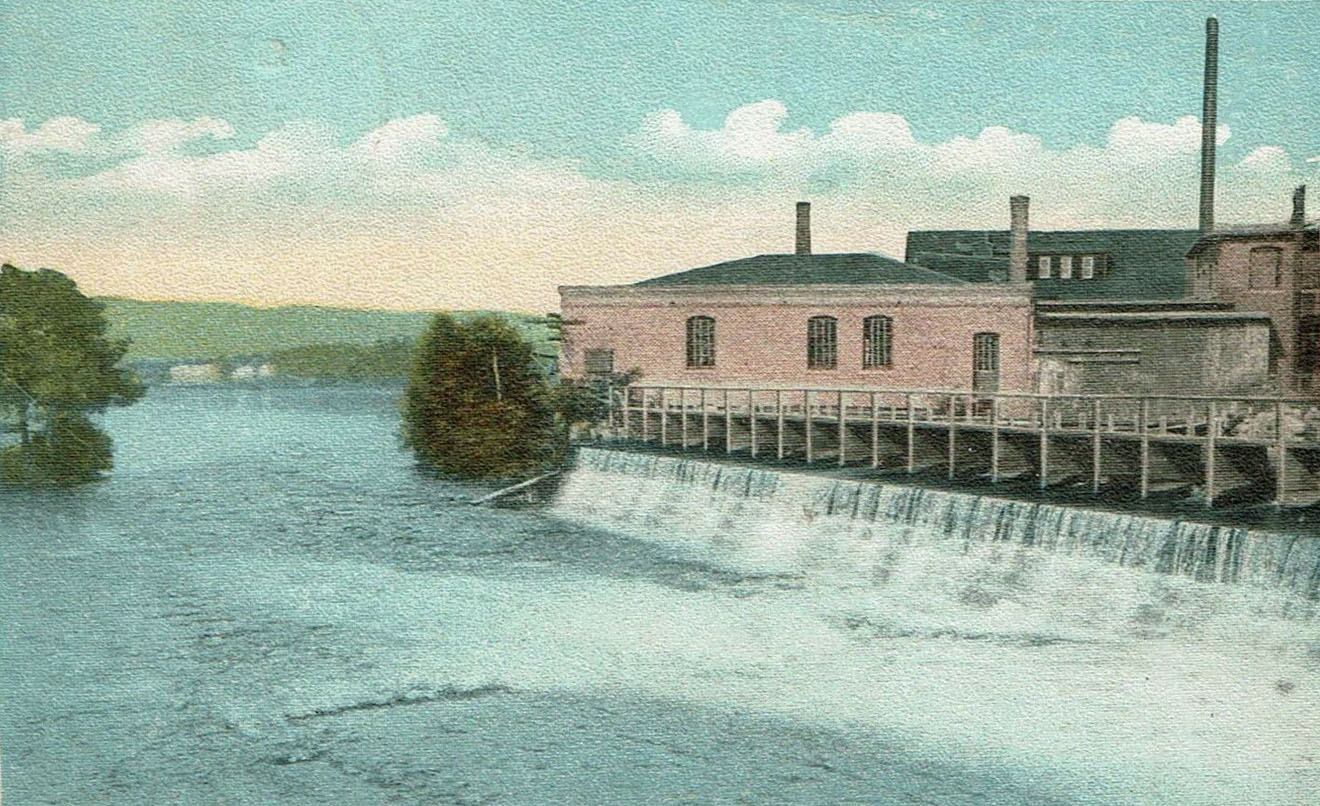

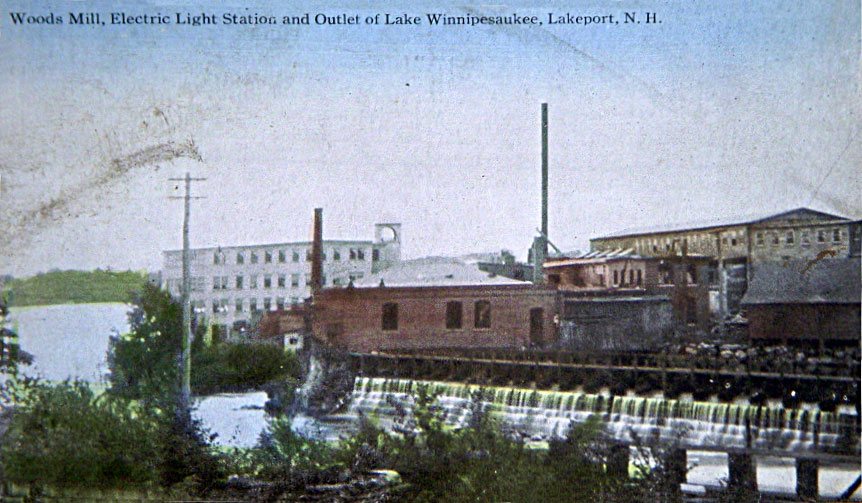

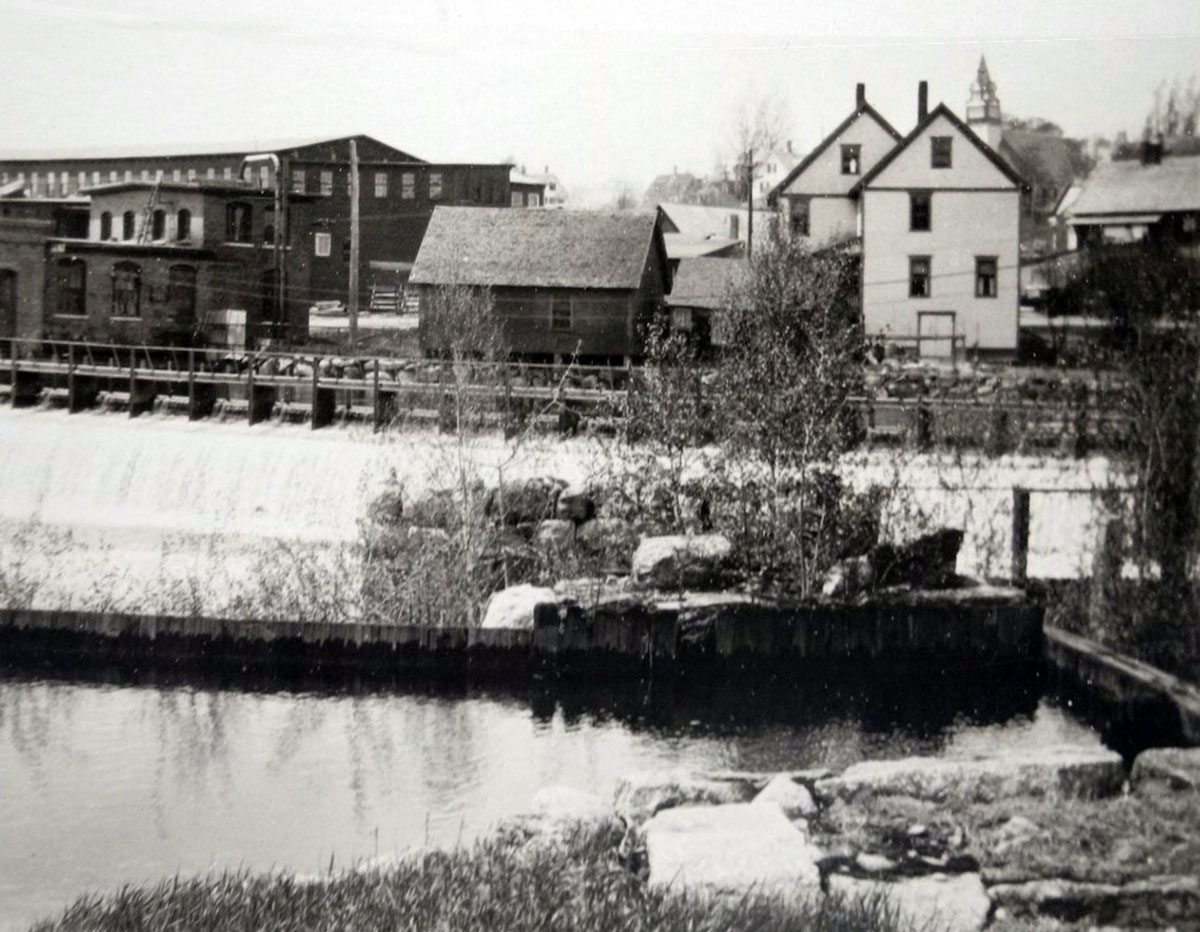

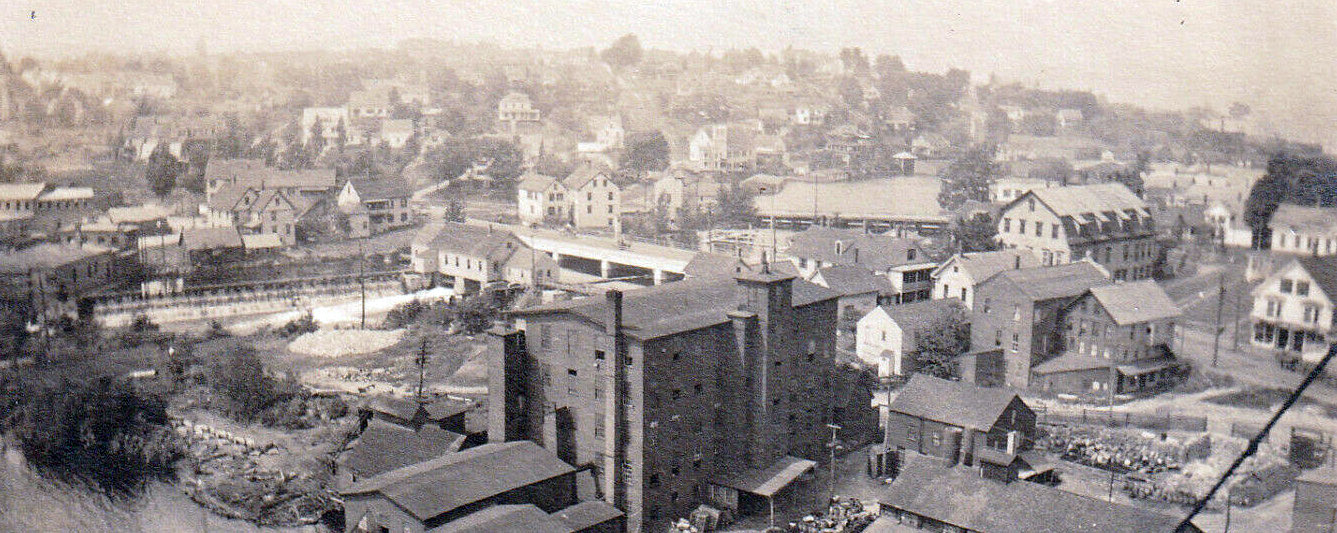

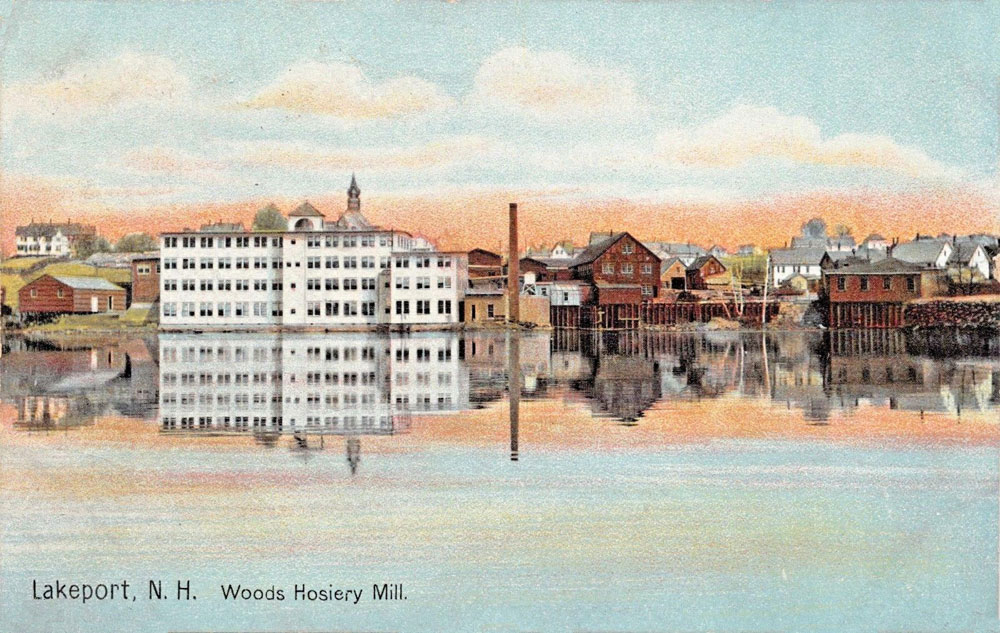

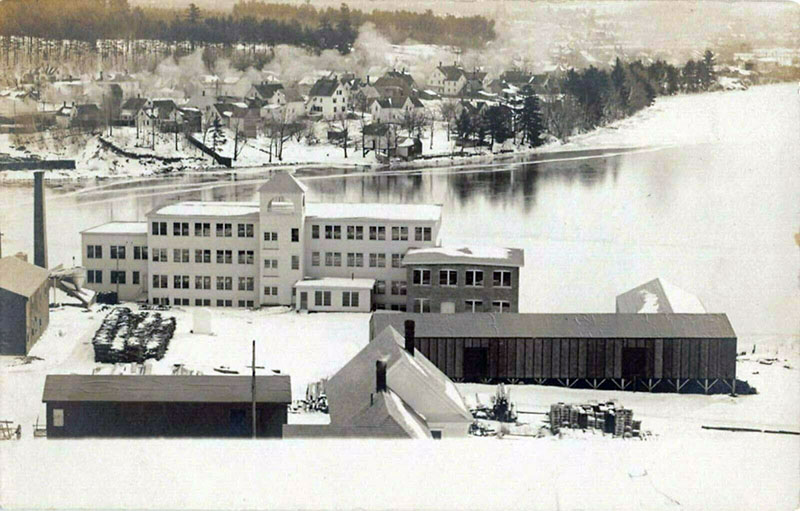

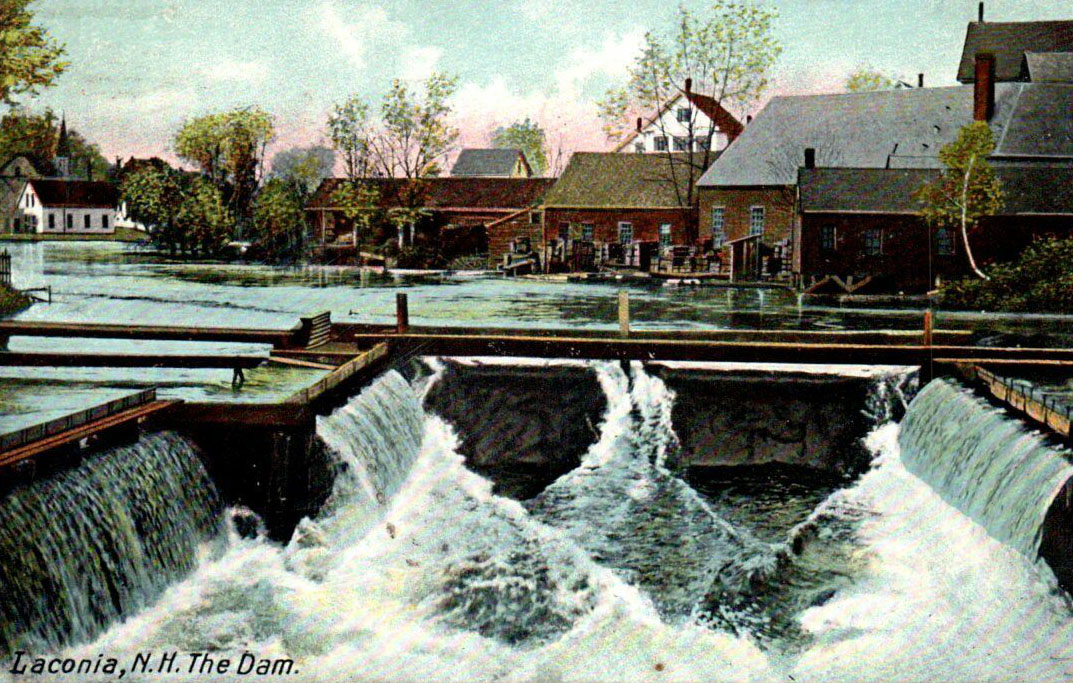

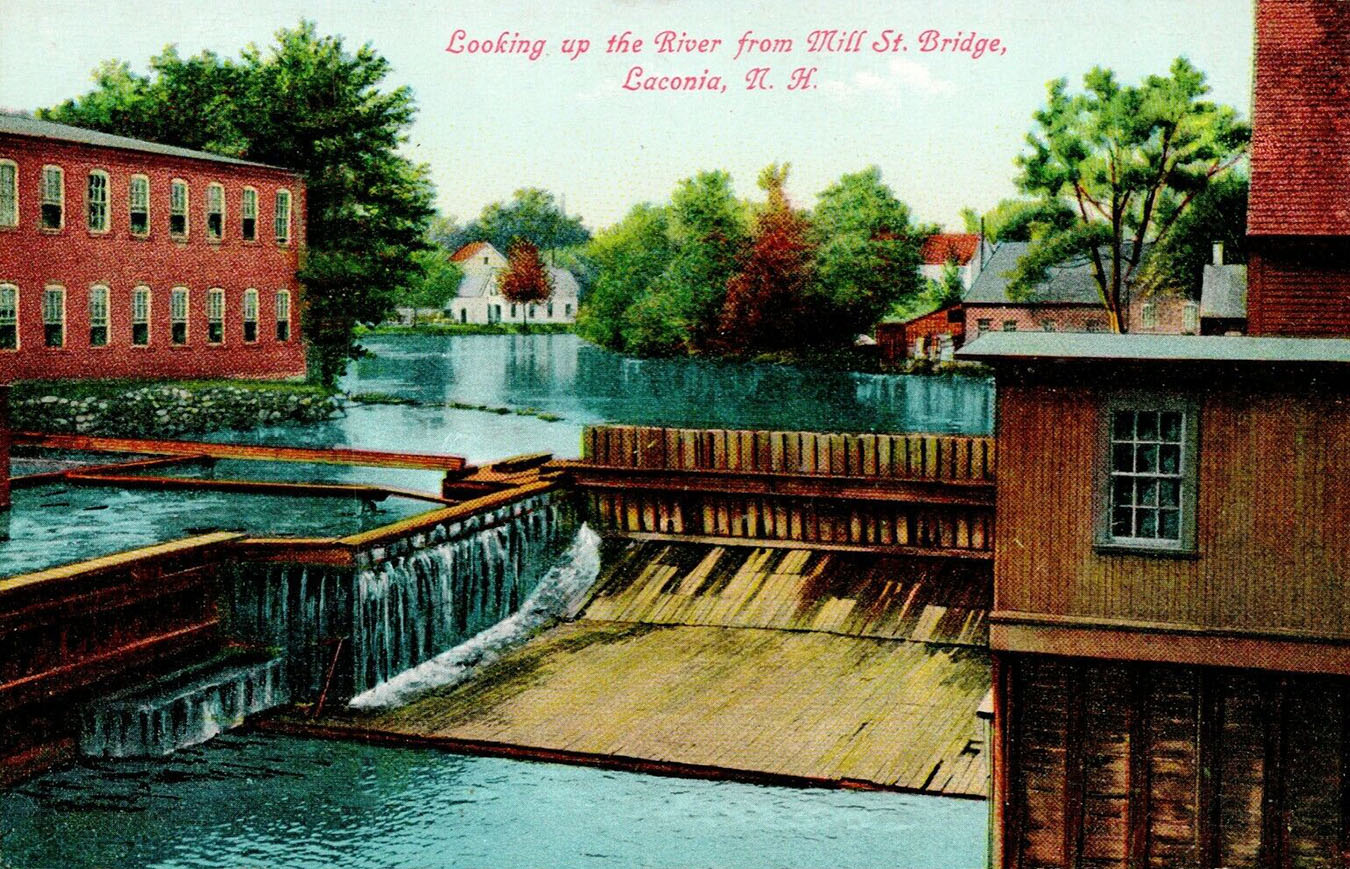

The Lakeport Wing Dam

The first Lakeport dam was built in 1781, the second in 1829. The third dam, built in 1851, was built to last out of stone, and it is still there today. In 1861, the wing dam, to the left in the postcards below, was built. The wing dam was downstream, on the Lake Opechee side of the main dam. The 1851 main dam flows between the concrete pilings under the dam house at the center of the photos. Another flow of the dam is visible from the sawmill to the far right. In 1943, the dam was sold to PSNH. Around 1957, the wing dam was filled in. On March 31, 1958, the dam became state property. For contemporary photos and more info about the Lakeport dam, click here.

The church steeple in the upper left belonged to the Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church, which was located at 25 Belvedere Street. The church was dedicated on February 16, 1892, and was destroyed in the Great Lakeport Fire, on May 26, 1903. Its congregation merged with the Weirs Methodist Church in 1963.

The brick building on the left was the powerhouse of the Laconia Electric Lighting Company, built in 1904 after the 1903 Great Lakeport Fire burned down the earlier powerhouse. The powerhouse ended operations in 1932; it was gone by the time the wing dam was removed in 1957.

On the left behind the brick powerhouse was the Woods Hosiery Mill, while behind it on the right was the Boulia-Gorrell Lumber Company. The lumber company buildings burned down on August 30, 1918.

The Woods Hosiery Mill

The wing dam provided waterpower to the Woods Hosiery Mill (below), which was located on the shore of Lake Opechee just north of the dam. The mill was rebuilt in 1904 following the Great Lakeport Fire of May 26, 1903, and was called Sweaterville when it was destroyed by fire for a final time on Christmas Day, December 25, 1968.

The Avery Dam

The original Avery Dam in Laconia was built in 1797. Made of wood, the dam provided power for Laconia’s mills and other industries for over a hundred and fifty years, until it was replaced in 1949, by the current concrete structure. An interesting walking tour, taking in the dam and other historical structures along the Winnipesaukee River, is described here.

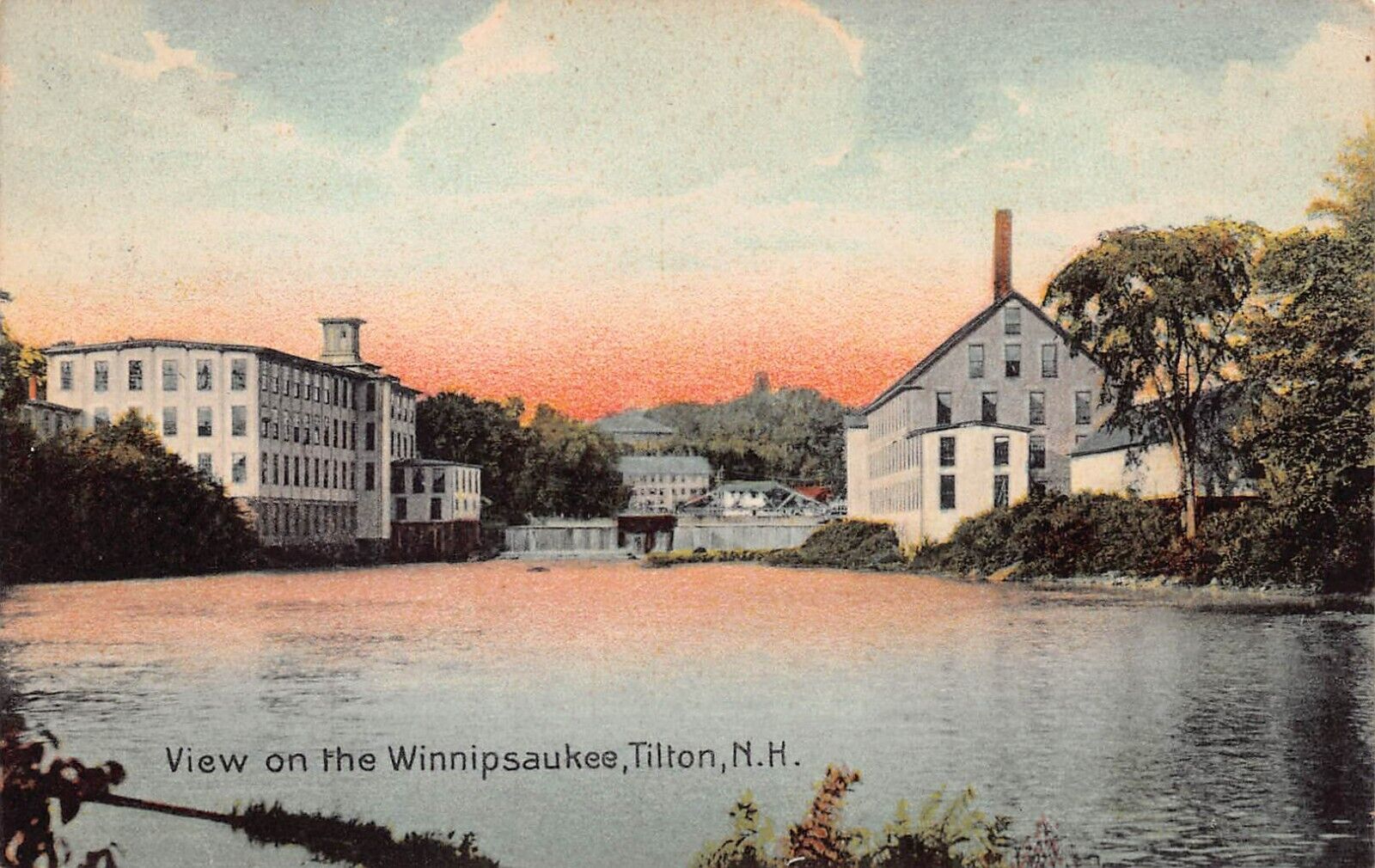

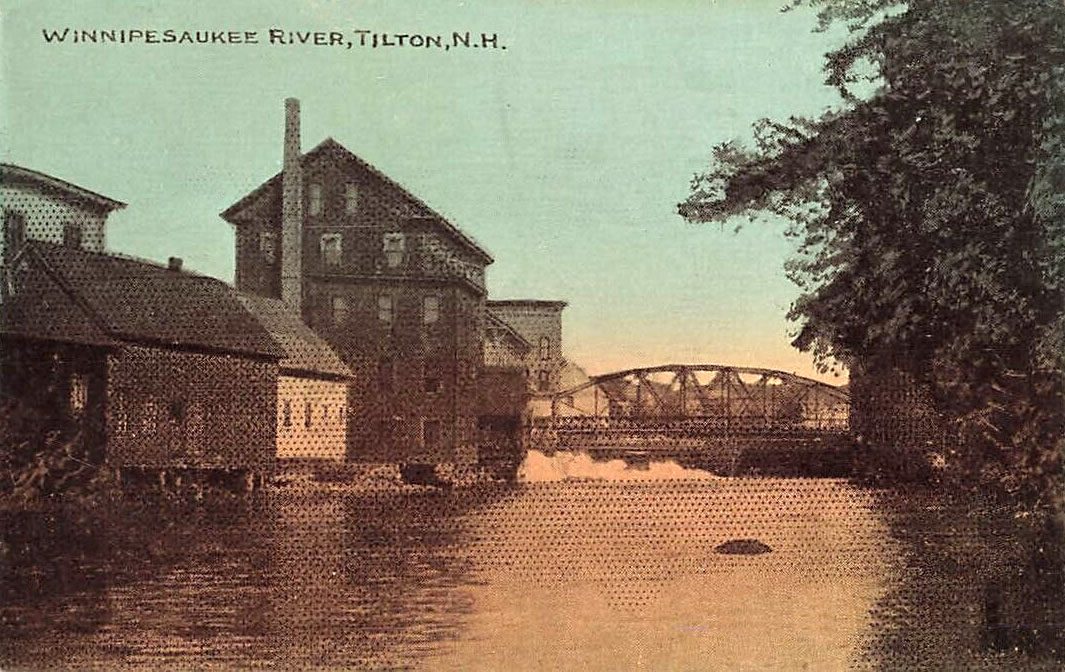

The Tilton Dams

The second Tilton Dam. Postcard postmarked in 1911. View is looking upstream. The lenticular bridge can be seen in the distance.

A detail from an 1884 map of Tilton shows that there were FOUR miller’s dams on the Tilton section of the Winnipesaukee River at the time. At each dam, there were often two mills, one on each side of the river. Going downstream, the mills were numbered on the map as follows. At the first dam, #21 was the A.G. Cook Saw Mill, and #15 was the Ballantyne & Fletcher Granite Mills. At the second dam, there were three mills: #20 was the Chas W. Blood Grist Mills, #18 was the R.N. Colvin Hosiery & Underwear Mill, and #16 was the Richard Firth Elm Mills. At the third dam, #22 was the N.H. Manufacturing Co’s Mills and #17 was the G.E. Buell Tilton Hosiery Co. At the fourth dam, there was only one mill, the #14 Tilton & Peabody Tilton Mills.

The first three dams were removed over the years. The Winnipesaukee River flows freely now where the first dam at Granite Street once stood. The second dam in the 1884 map, depicted with an iron lenticular truss bridge crossing, is the dam seen in the two old postcards above. The truss bridge was replaced long ago, and is now the steel and concrete School St bridge, with a free-flowing river underneath it. If it were still around, the third dam would stretch between today’s Riverfront Park and the railroad tracks on the opposite side of the river, but it is long gone. Only the fourth dam, now known as the Clement Dam, remains.

The Franklin Dams

The Franklin Mills Dam, 1930s. There once were several mills on the Winnipesaukee River in Franklin. The last two mills shut down in 1971 and 1984.

The Riversports Park

In Franklin, the Winnipesaukee River drops about 100′ from the Cross Mill bridge (where Cross Mill Road crosses the river from Franklin to Northfield) down to the Sanborn bridge (where Route 3 crosses the river just south of Sanborn St). Just past the Sanborn bridge is the site of the Mill City Whitewater Riversports Park. The park officially opened on June 17, 2022. The first park feature was a stationary wave that allows kayakers to hone their skills while remaining in one spot, and an amphitheater for spectators to watch the river activities. Two more whitewater features are planned. When completed, the park will consist of 13 acres with 21 acres of adjacent preserved land. The park will include both sides of the river, and a pedestrian bridge to cross over the churning water below.

In the photo below, the Franklin Mills dam can be seen just downstream. Not seen are a line of buoys that now separate the dam from the Riversports park.

The Franklin Mills

An 1884 map of Franklin shows FIVE miller’s dams on the Franklin section of the Winnipesaukee River at the time, when Franklin was known as the “Paper City”. Going downstream, the mills were numbered on the map as follows. At the first dam, #28 was the Franklin Falls Pulp Co. The second dam was #26 Pulp Mill No. 2. The third dam was #24 Pulp Mill No. 1 and #23 Paper Mill No. 1. The fourth dam was #29 Aiken’s Hosiery Mills* and #31 The Franklin Mills. The fifth dam was #24 Paper Mill No. 2 and #32 Sulloway’s Hosiery Mills. With the exception of the hosiery mills, all of these mills belonged to the Winnepiseogee Paper Company.

By the 1930s, many of these mills had closed. The International Paper Company had bought the Winnepiseogee Paper Company in 1898 and gradually moved paper production elsewhere. A series of floods in the 1930s breached the first three dams, which were not rebuilt. The fourth dam at the Franklin Mills remains, as does the fifth dam, now known as the River Bend power station.

*As a young man, Walter Aiken (1831-1893) invented and patented a circular knitting machine with moving needles. Key to this operation was the “latch-needle”, in which the eye of the needle opened after the start of a stitch and automatically closed to finish it. The resulting fabric tubes could then be cut to length and the heel and toe pieces stitched on by hand to make a complete sock. Aiken continued to improve his machines and needles, garnering over 40 patents for his inventions and improvements. His large mill was built in 1864 on East Bow Street, and his Franklin Needle Company became the world’s largest latch needle manufacturer. No trace of the mill remains today.

The Franklin & Tilton Railroad

The 1884 map detail above does not show any railroad tracks. That is because the Franklin and Tilton Railroad, built expressly to service the various mills in Franklin, was not completed until 1892, 8 years after the map was published. The railroad branched off the B&M White Mountain line near downtown Tilton. Upon reaching downtown Franklin, there were a number of sidings that serviced the mills on both sides of the river. The railroad continued through Franklin until it crossed the Merrimack river to join the B&M Northern line at Franklin Junction. In March, 1936, the Merrimack crossing bridge was destroyed by floods, and in December, 1941, the B&M abandoned the section from downtown Franklin to the Junction. The remaining portion of the railroad was used sporadically until it too was finally abandoned in 1972. The remaining portion was converted to the Winnipesaukee River Trail in the 2000s.

The 1927 map detail below shows the exact route of the Franklin and Tilton railroad. The railroad crossed the Winnipesaukee River on the Sulphite Bridge about 1/4 mile before downtown Franklin, then crossed back just before the Sanborn bridge. From there it ran south between what are now Franklin St and Woodridge Road until reaching the east bank of the Merrimack. At that point, a siding ran north to the Sulloway Hosiery Mills. That siding still exists. The main railroad continued down the east bank for a ways before crossing over to Franklin Junction. This detail is from the 1927 USGS (United States Geological Survey) Penacook and Gilmanton NH Quadrangle.

The River Junction

Aerial view of the river junction in Franklin. The confluence of the Pemigewasset (larger river on the left) and the Winnipesaukee (narrow river on the right) is just off the photo in the bottom left corner.

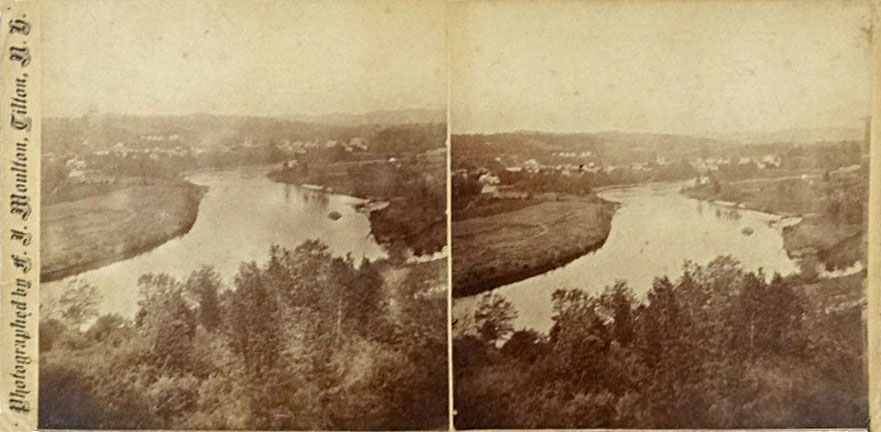

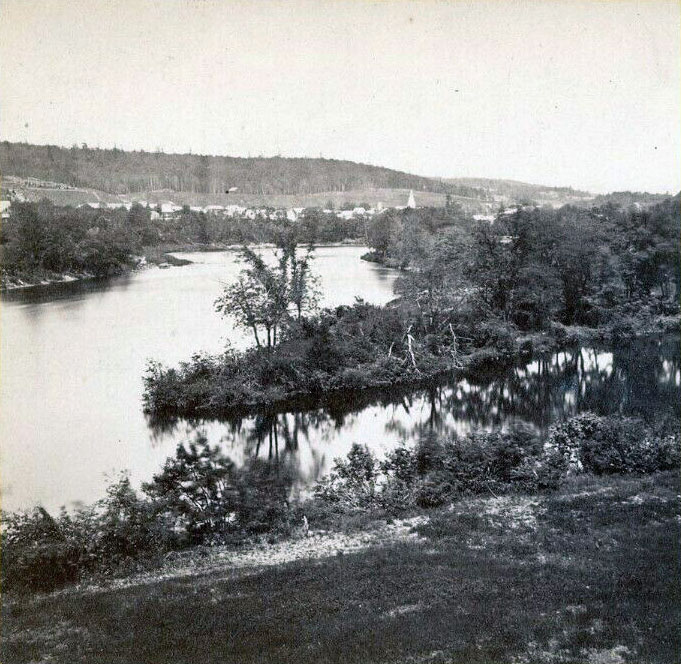

Stereoview of the junction of the two rivers.

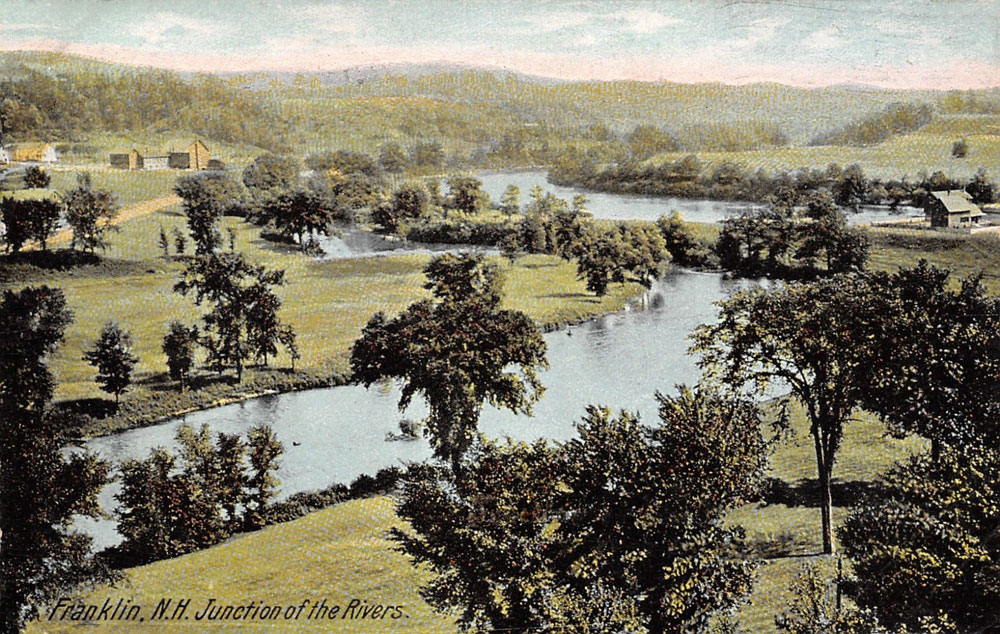

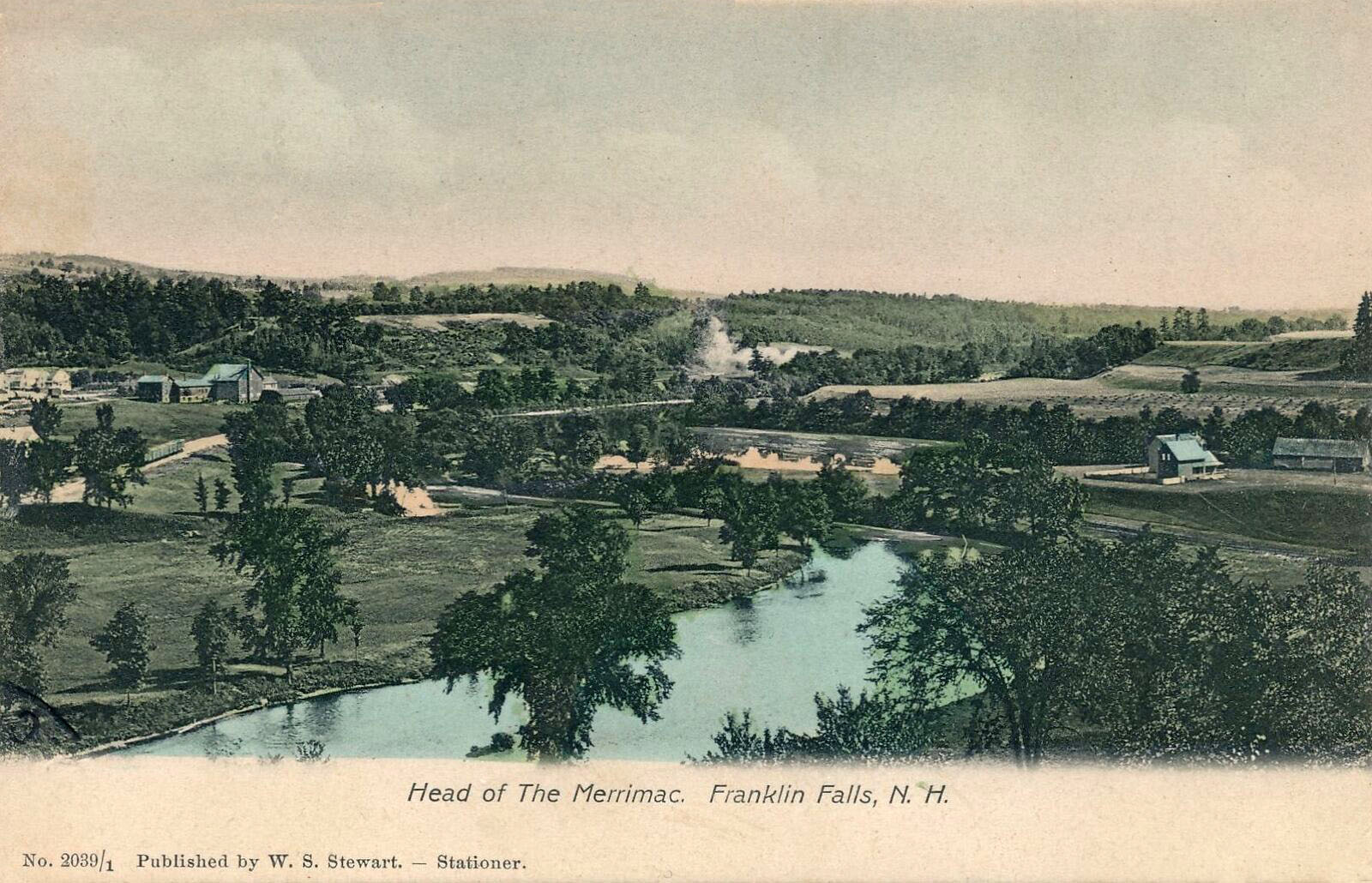

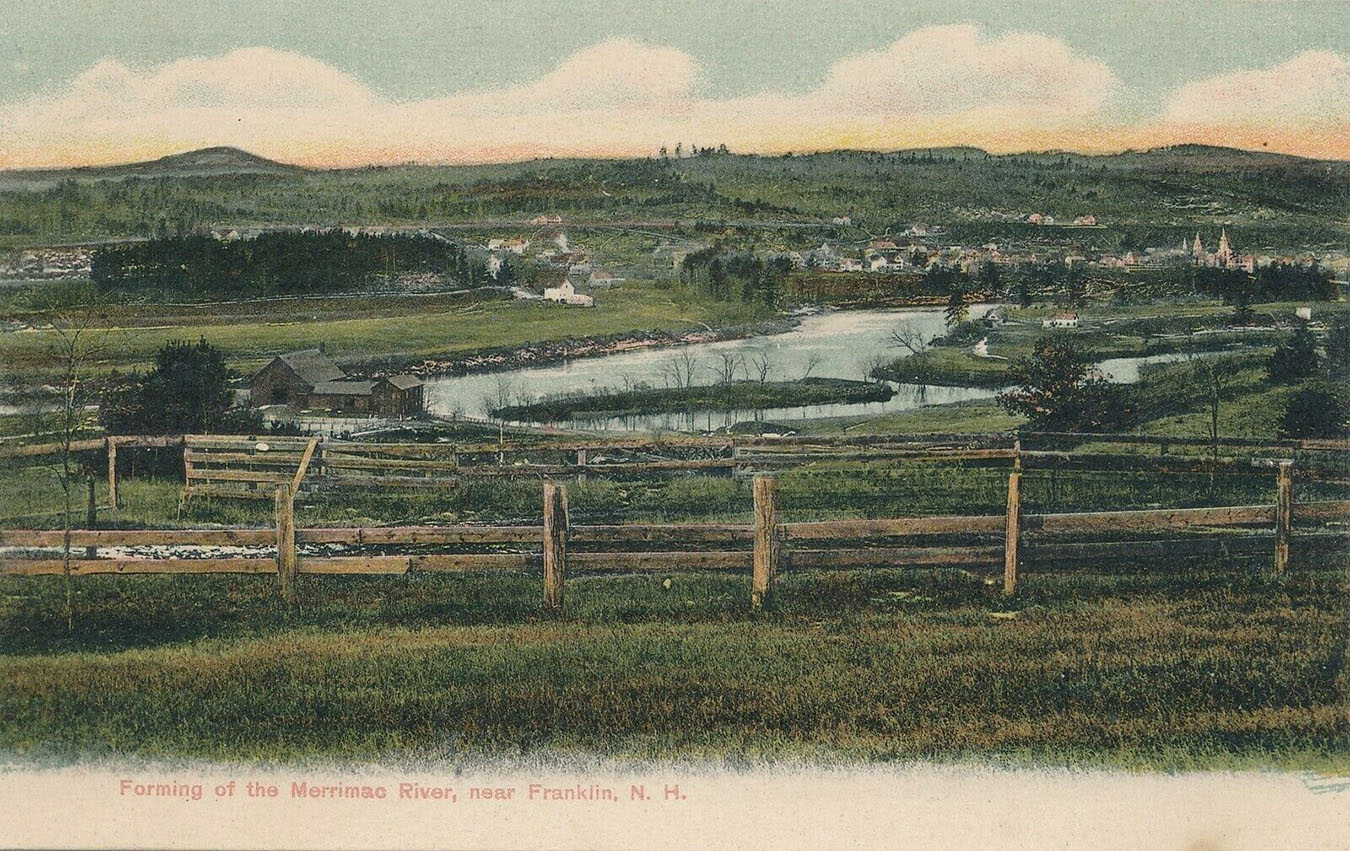

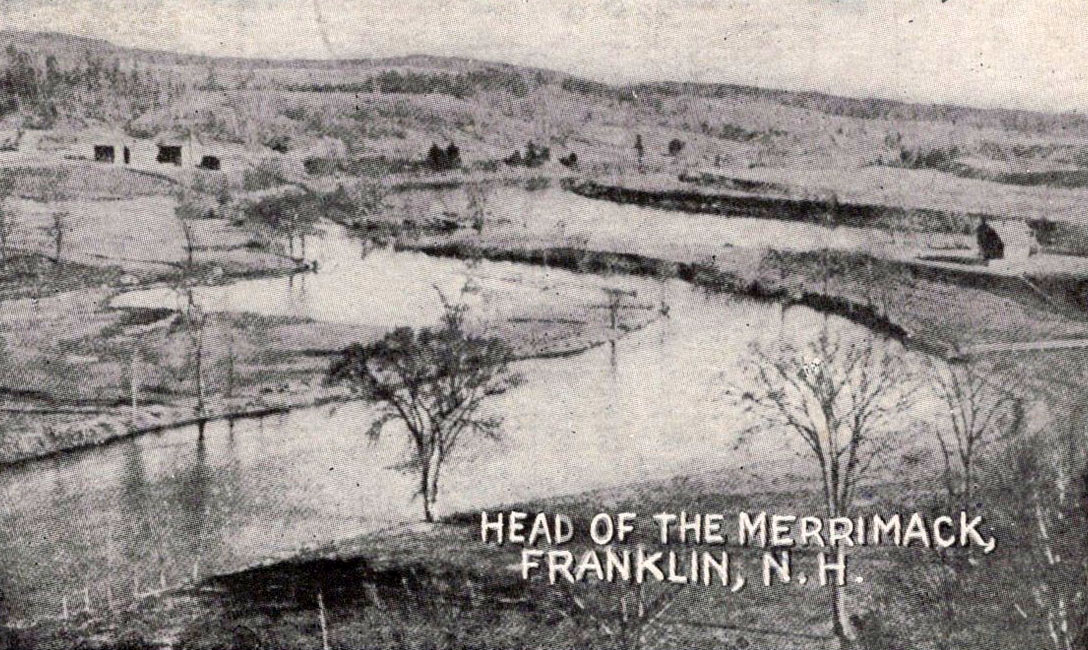

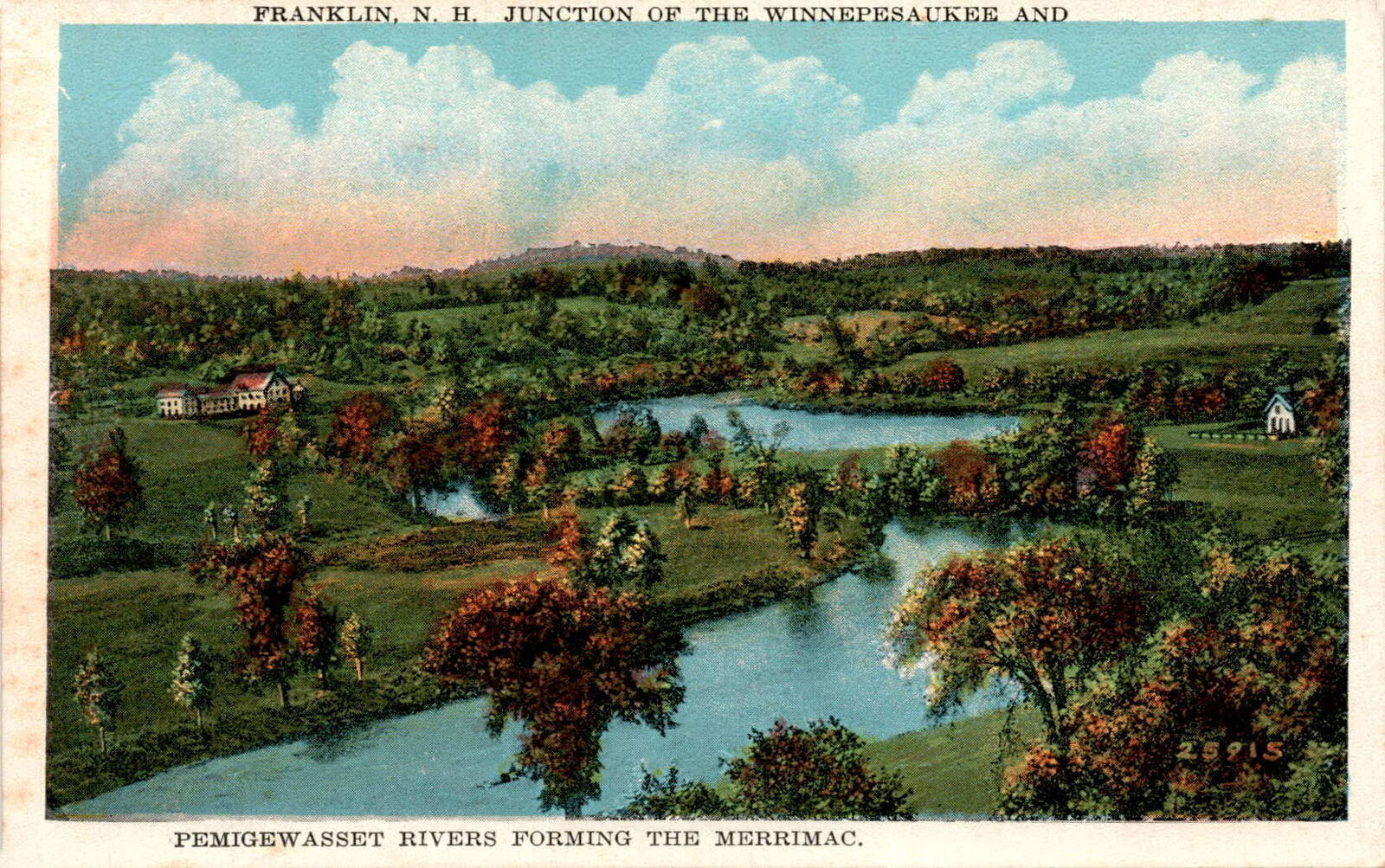

Old postcards of the river junction.

“Junction of the Winnipesaukee and Pemigewasset Rivers Forming the Merrimac, Franklin, N.H.” On the left, the Pemigewasset enters from the North; on the right, the Winnipesaukee enters from the East, forming the Merrimac, which continues South to enter the Atlantic ocean at Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Great Bay, Round Bay, Long Bay

In 1871, Martin A. Haynes, publisher of the Lake Village [Lakeport] News, proposed the new name Paugus for Long Bay, “in honor of the old Indian chieftain who once ranged this region and the country to the North of it.” Hayne’s friend and associate, Professor J. Warren Thyng, proposed the name Opechee for Round Bay, as robins “used to be numerous in the vicinity”, and “Opechee meant robin in the Indian language”. The two names stuck. The Professor had come across the word Opechee in Henry Wadsorth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha. One of Longfellow’s most recognizable works, The Song of Hiawatha is based on an accumulation of Native American stories and legends. However, Opechee is a word taken from the Sioux language, not the native Abenaki’s.