Original Ice House

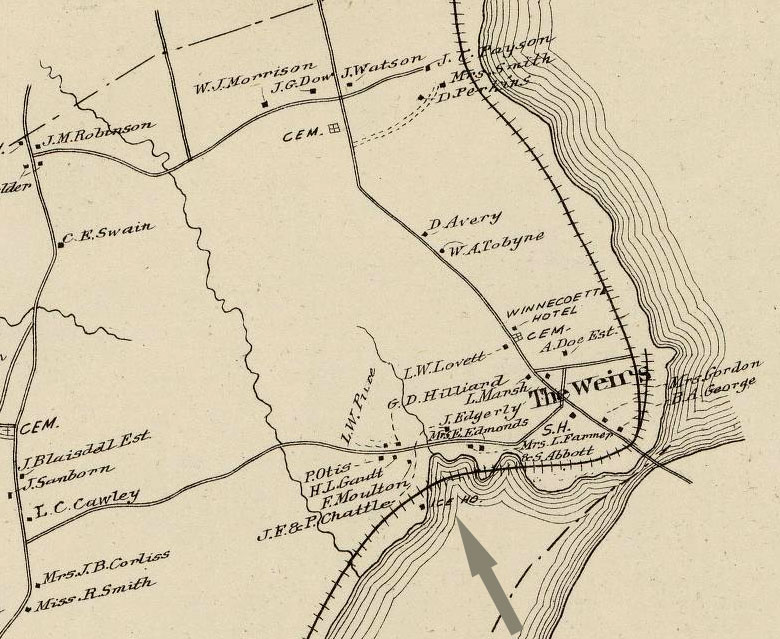

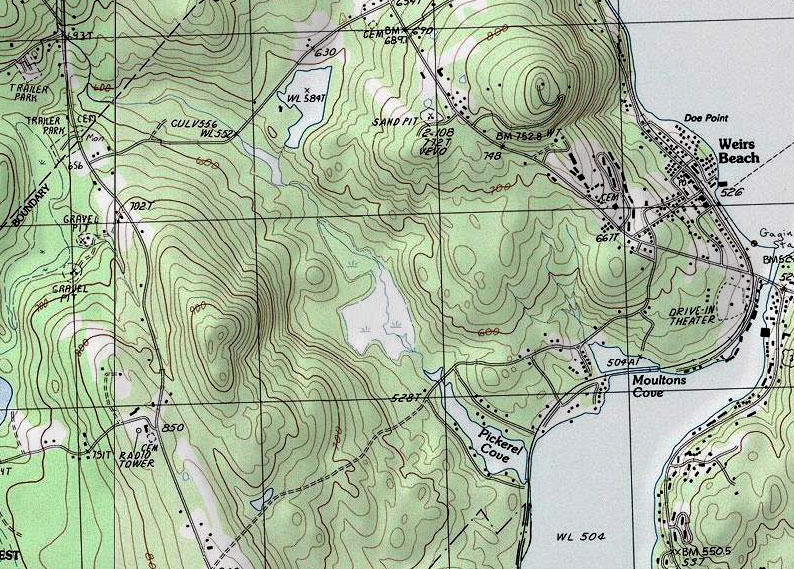

Before the advent of modern refrigeration, one of the main economic activities in Weirs Beach was harvesting ice from frozen Lake Winnipesaukee, and storing the ice for later use. As can be seen in the 1892 map below, the location of the original ice house in Weirs Beach was at the southern edge of Pickerel Cove, on Paugus Bay. The ice house’s location adjacent to the railroad tracks made perfect sense, as the ice could be easily loaded onto freight trains and shipped elsewhere. According to a January 24, 1909 Laconia Democrat article, “….the Morrill-Atwood Ice Co. of Wakefield, MA, who supply many of the large hotels in Boston, were filling their ice houses, near the Weirs on Lake Paugus.”

In 1909, this was a very competitive industry, and there were many companies involved, as the raw product was free, and little capital was required to enter the business. In March of that year, the Laconia Democrat noted that the ice companies had “finished cutting for the season. The total amount cut by the Independent being 125,000 tons, and 35,000 tons by the Lawrence Ice. Co. A party from Boston, who has excellent courage, commence this week, cutting 100 car loads at Gardner’s Grove.”

Cutting of ice was a major winter industry from the late 1800s through WW II and even into the late 1940s. A February, 1948, Laconia Citizen article noted that the ice harvest was underway on Lake Paugus by the Rudzinski family of the Laconia-Lakeport Ice Co. That particular company continues on into the present day, as the Laconia Ice company, although nowadays of course all ice is manufactured. The webmaster of this site was a childhood friend of Tommy Rudzinski, the current owner of the company.

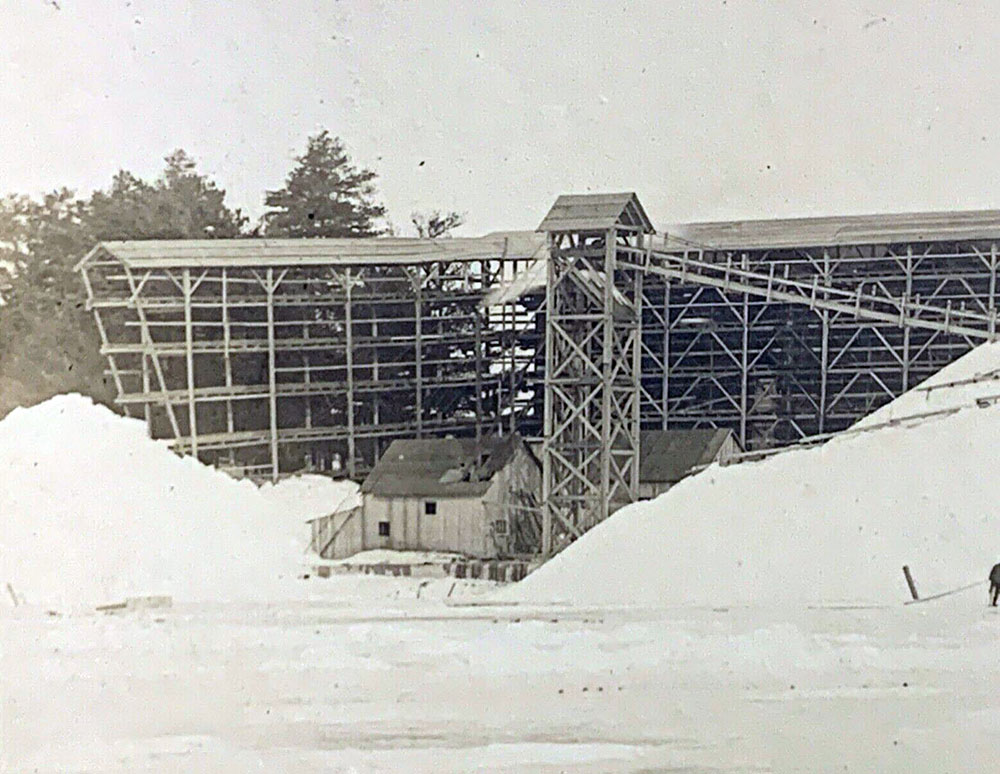

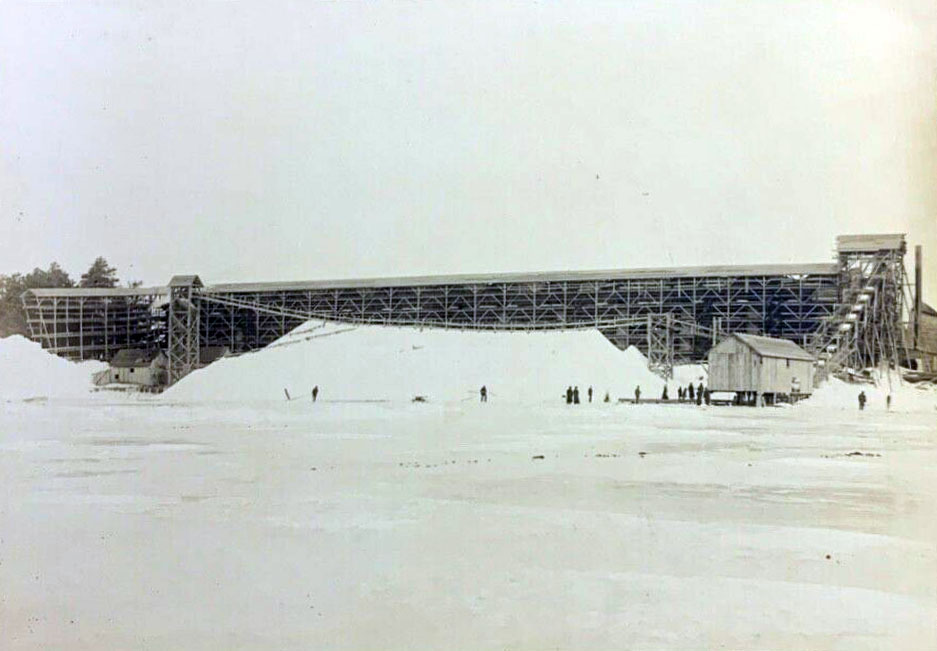

While no photo of the Weirs Beach ice house is available, below are severals pictures of an enormous ice house located in Lakeport, by far the largest ice house in the area. On January 17, 1909, according to the Laconia Democrat, the Independent Ice Company was filling their ice house in Lakeport, the ice “being from twelve to fifteen inches thick.” Ice needed to be at least 8″-12″ thick to be economical for harvesting, so the 1909 harvest was unquestionably a good one.

Below is a 1915 picture of men harvesting ice at the Independent ice house. Many of the men are holding ice picks, used to pull the ice blocks along. We are looking at the ice house from the lake (Paugus Bay). Union Avenue and the Lakeshore Railroad (1890-1935) both ran parallel to the house directly in the rear, so the ice could easily be transported to customers. Clearly visible in the photo is the conveyor belt which dragged the big blocks of ice up and into the storage facility. There, the blocks of ice would be stacked to the ceiling and then covered with sawdust and straw to insulate them from the coming spring and summer heat. The building in front of the conveyor belt contained a saw mill that would prepare the raw blocks by cutting them down into a smooth, uniform size.

The optimal construction and specification for ice houses was detailed by Walter G. Berg in his 1893 book, Buildings and Structures of American Railroads. According to Berg, most ice houses were of wood frame construction, due to the economic cost and because wood is not a good conductor of heat. The features critical to a good ice house design were non-heat conducting walls, the prevention of air penetrating the house from the sides and bottom, ample ventilation on top of the ice, and good drainage. The walls were typically filled with sawdust, shavings, ashes or another nonheat-conducting material. Holes under the eaves allowed any moisture in the building to evaporate. The ice house was painted a light color and doors and ventilator openings were located on the north side of the building. Ideally, the doors would be arranged at different levels to facilitate the handling of ice into and out of the house. Small board windows half-way down the walls allowed for the circulation of air. Larger ice houses were divided into compartments so that the ice is only exposed in one compartment at a time when the doors are opened.

Here are more pictures of the Independent Ice Company ice house. The center picture shows the whole ice house, while the left and right pictures show blown-up details of each side. The ice house was huge, nearly the same size as a football field. (Football fields are 300′ x 160′.) The ice house was 300 feet wide, 144 feet deep, and 44 feet high. In 1936, it burned down in a mid-winter gale. The property was then sold, where it first became the Oxbow Cottages, then Barton’s Motel, and now the Lakeside at Paugus Bay condominiums.

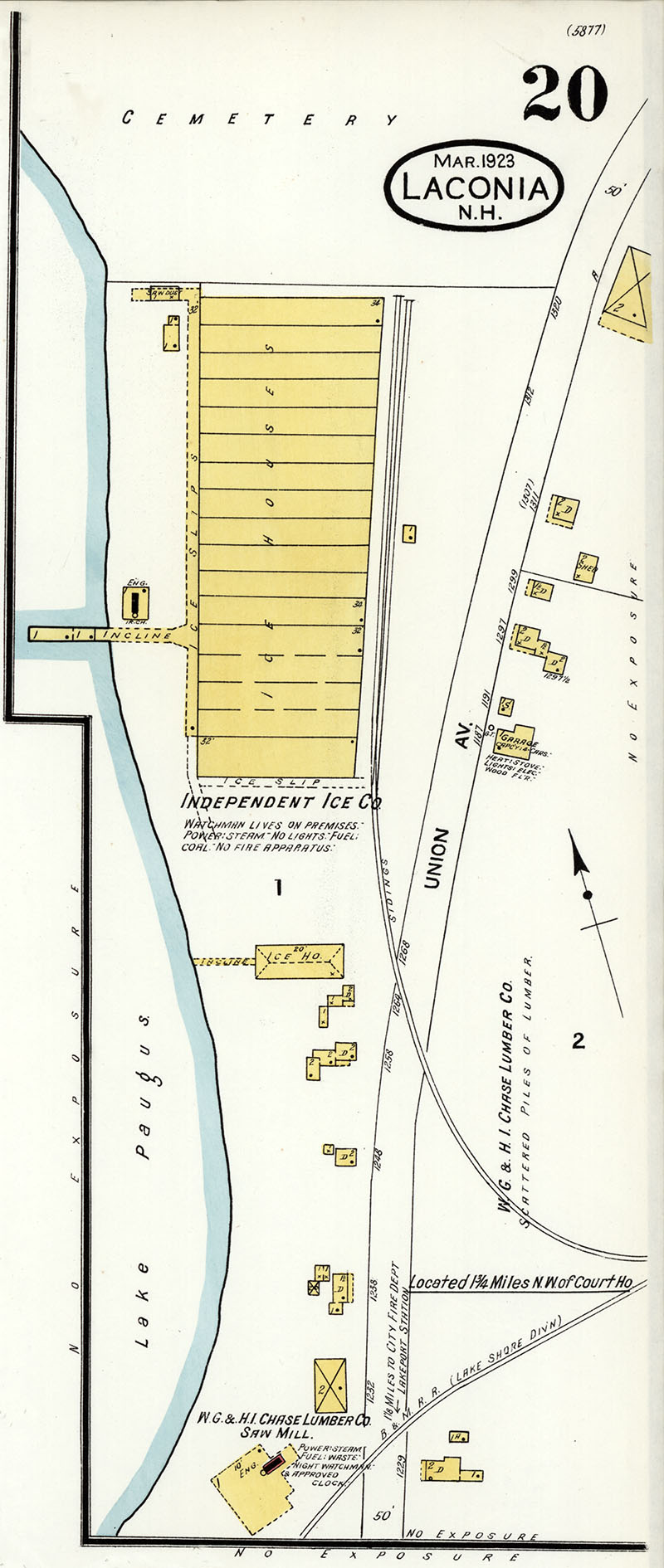

A detail from the 1923 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Laconia shows that the Independent Ice House had their own railroad siding branching off of the B&M Lakeshore Railroad. As also can be seen on the map, the property abutted the Bayside Cemetery.

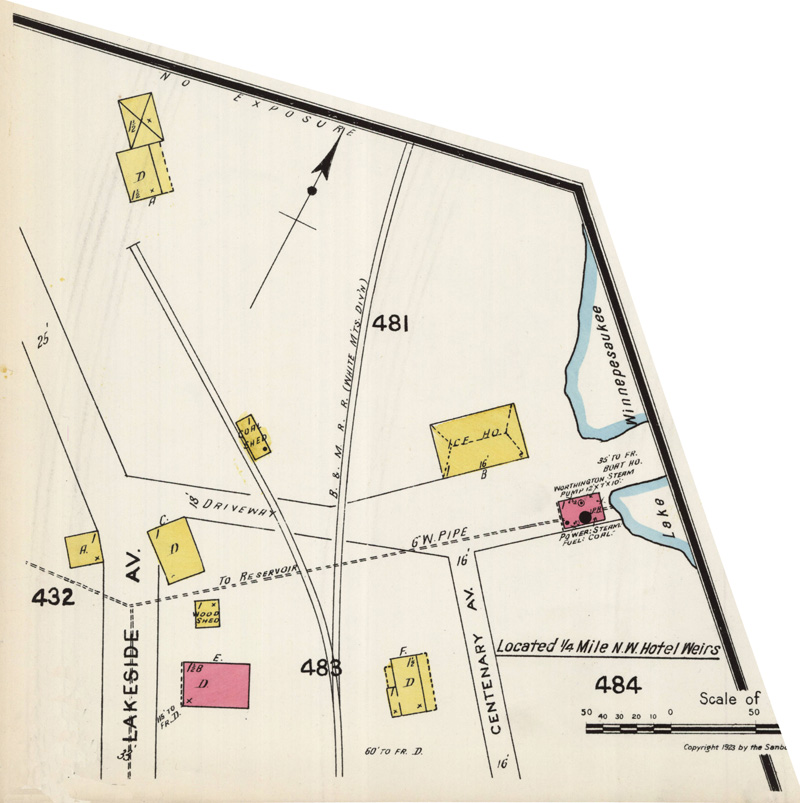

There was also an ice house on the Lake Winnipesaukee side of Weirs Beach, where today there is a marina at the northern end of Centenary Avenue. The detail below from the 1923 Sanborn Fire Insurance map shows the location of that ice house. A February, 1919 Laconia Democrat article noted that “The Metropolitan Ice Co. at the Weirs had its ice houses about full…”

Interestingly, even though water freezes at 32 degrees, the Lake cannot freeze over until all of its water cools to 39 degrees in temperature. Here is an explanation as to why by Winnipesaukee.com member This’nThat: “Water is most dense at 39 degrees, so water at that temperature sinks, and warmer lake water rises to the surface — which also must be cooled to 39 degrees — which sinks, is replaced by warmer water, and so on until everything is at 39 degrees. When that temperature is reached, there is no more warm water to rise to the surface. Therefore, the surface water can now begin to freeze and ice begins to form and stay on the lake. This “water density at 39 degrees” also explains why shallow lakes freeze quicker than deep lakes like Winni. Deep lakes have much more water that needs to be cooled to 39 degrees.”

Ice-Out is declared when the cruise ship MS Mount Washington can visit all of its main ports of Weirs Beach, Wolfeboro, Alton Bay, Center Harbor, and Meredith. This usually occurs around April 20, give or take a week. The earliest Ice-Out was on March 29, 1921, the latest on May 12, 1888. In 2008, Ice-Out occured on April 23.

According to a Laconia Citizen article dated January 10, 2009, melting occurs at an accelerated rate once the average air temperature hits 34 degrees. Why this is so needs a good explanation.

Below, men using ice saws are cutting ice in front of downtown Wolfeboro in the1880’s. Back then, ice harvesting was performed with a combination of manual labor and horse power. If the ice was thick enough for ice harvesting, it was also thick enough to support the weight of horses. The process using horses would go something like this. First, the ice would be cleared of any snow. Then, horses would drag a cutting plow to make initial cuts 3″ deep, scoring the ice into squares of 22″ x 44″. Another pass of the horses would cut the ice to about 2/3 deep of whatever thickness the ice happened to be that year. The final cut would be done manually. Men would then pull out the blocks with ice picks and load them onto wagons to be pulled by the horses off of the ice. This man and horse process continued until around 1915, when the first mechanized ice cutters were introduced. The NH Historical Society Museum in Concord has a mechanized ice cutter on display.

One of the last ice harvests in the USA continues nearby on Squam Lake, where the Rockywold-Deephaven camps have been harvesting ice since 1897. Once the ice reaches the required thickness of at least 13″, two hundred tons of ice, comprising about 3,600 blocks, are harvested over several days. The 16″x19″ blocks, weighing up to 120 lbs each, are then stored in two sheds until summer, when they are wheelbarrowed to the antique iceboxes of camp guests.

Modern guests should not feel any queasiness from consuming this natural product. In 1890, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health studied the quality of melt water from clear lake ice, and discovered that it was safe to drink even if the lake itself was polluted. This is because the directional freezing that occurs on the surface of a lake pushes not only the cloud of dissolved air, but also everything else in the lake water downward, reducing the bacteria count by up to 99%.

This principal of freezing from the top down has been utilized to create kits to make clear ice in the freezer compartment of your modern frig. In a regular ice cube tray, the ice freezes from all sides toward the center of the cube, trapping a cloud of dissolved air and other impurities in the center. The ClearlyFrozen ice cube tray, however, works just like a lake in the wintertime, by freezing from the top down. The “directional freezing” process pushes the air to the bottom of the ice cube and through a hole at the bottom of the tray, leaving you with clear ice.

Blocks of ice, stacked high on two sleds pulled by a 2-horse team, are seen in front of the Clinton S. Masseck store in this circa-1919, real photo postcard. Masseck also owned a gift shop in Weirs Beach from 1906-1924.