Travel by Train

What is the funnest way to get to Weirs Beach?

The FUNNEST way to travel to Weirs Beach is by train. From Lakeport or from Meredith, take a scenic ride along the lake on the Winnipesaukee Scenic Railroad to Weirs Beach.

History of the Route 3 Railroad Bridge

Above, an October, 2019 photo of the Route 3 railroad bridge at the entrance to Weirs Beach.

In 1848, when the Boston, Concord and Montreal railroad reached Weirs Beach, a grade-separated crossing was needed where the railroad intersected with the main horse and carriage thoroughfare. A split granite abutment was built, with the train passing underneath the roadway just before its arrival at Weirs Steamboat Landing.

In the early 20th century, the overpass carried increasing numbers of automobiles. After the first state-aid highway law was passed in 1905, US 3 was improved as the middle road of three north-south trunk lines. In 1907, it was named the Merrimack Valley Road. It was the most traveled road in the state when it was renamed in 1921 for famed lawyer and statesman Daniel Webster. Finally, in 1926, it was numbered US Route 3.

During the Great Depression, a new bridge was funded in 1933 by the federal Reconstruction Finance Corporation. The old stone abutments were incorporated into a single-span concrete slab bridge, with cast concrete rails, lamp posts and a sidewalk offering pedestrians a scenic view of the lake.

In 2020, shortly after the above photo was taken, the overpass was rebuilt while retaining the 1848 granite abutments. Now, a summer day sees more than 13,000 vehicles cross over the railroad tracks on US 3.

The Semaphore Tower

Below is an October, 2019 photo of the semaphore signal tower, just before the railroad bridge. Its use was to direct train movements and prevent train collisions. The 31′-high tower featured two pivoting arms, colored lenses, and lamps to illuminate the lenses. The angle of the arms and color of the lenses would signal to trains to stop, proceed with caution, or the all-clear. The tower, manufactured by the Union Switch and Signal Co., of Swissvale, PA, was installed in 1910, and retired in 1961. The spectacles, which held the colored lenses and blades, were removed when retired, along with the lamps.

Seen just past the tower is a round structure half-buried in the ground. This was the battery well for the semaphore. Made of concrete with a steel cover, the well contained a bank of 16 batteries, which powered the arm motors and lamps.

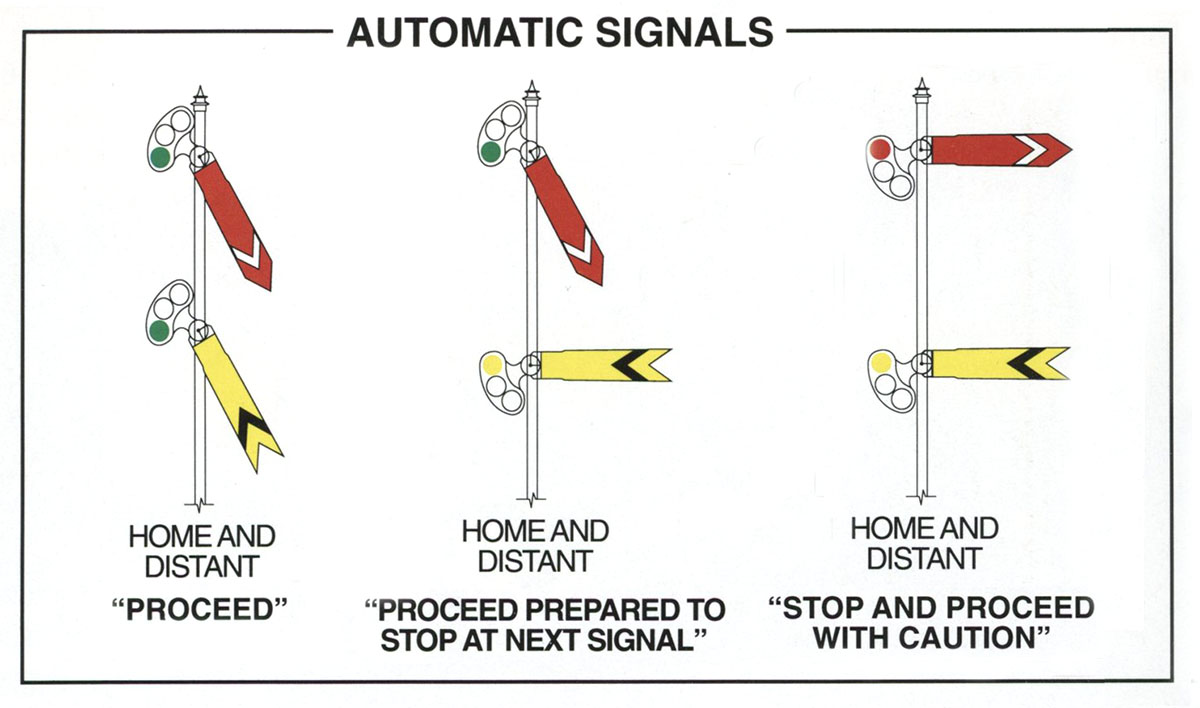

This particular semaphore tower was known as a “Style B”. Over 2500 of the towers were installed throughout the B&M railroad system between 1895 and 1925. Most were of the two-arm, “stop-clear”, “home and distant” variety. The stop indication had the blade positioned horizontally, while the clear indication had the blade swung down 60 degrees. The phrase “home and distant” refers to the functions of the two blades. The top blade looked at the track immediately in front of the signal (at ‘home’), while the lower, ‘distant’ blade repeated the position of the next home signal ahead.

As a train accepted and passed a signal, one arm would go to its “Stop and proceed” indication. In single track territory, there was an overlap of blocks, so the home arm wouldn’t clear until the train was much further beyond the next signal. The distant arm would clear as soon as the next home signal down the line cleared, giving a “Proceed” indication.

The arm blades were made of ash. Home “permissive” arms were red with a pointed end and white stripe. (A “permissive” signal could be passed after a complete stop.) Distant arms were yellow, with a forked, fishtail end and black stripe.

The position of the arms was only of use during the day. The arm positions could not be reliably discerned at night, so the colored spectacles would come into play. Home spectacles showed red when horizontal and green when cleared. Distant spectacles showed yellow when horizontal and green when cleared.

Similarly, the color of the spectacles could not be reliably seen on a sunny day. It was the combination of the arms and spectacles that allowed safe train operations around the clock and in any weather.

See the illustration below for an explanation of the configuration of the arms and the color of the spectacles.

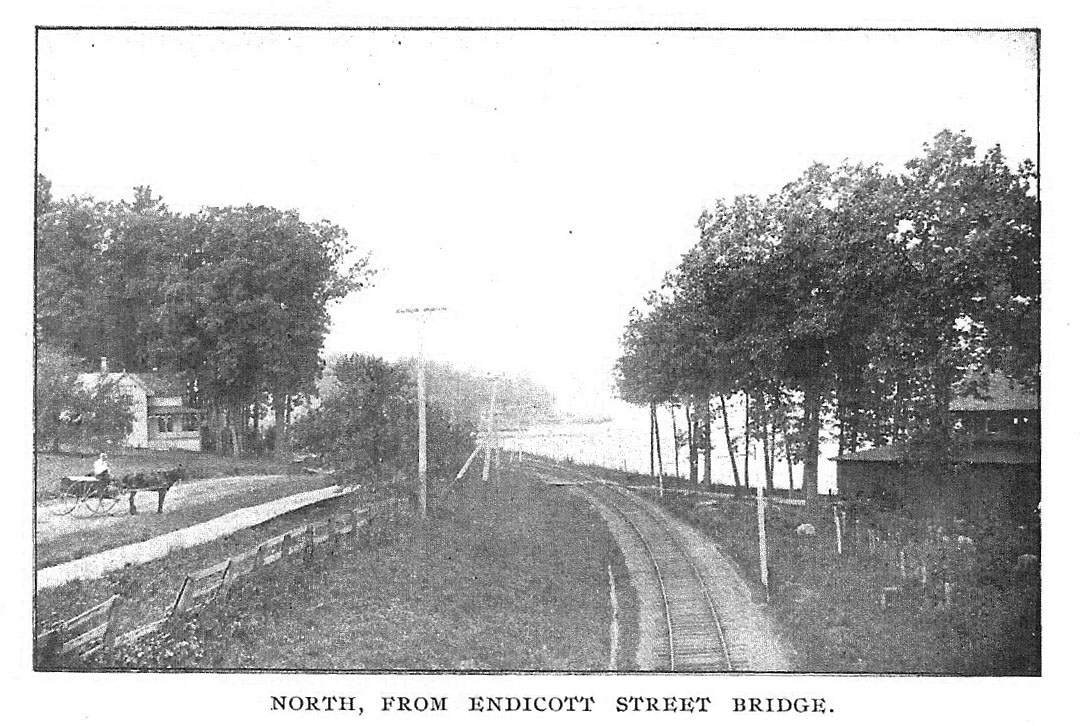

A view from the railroad bridge in the 1890s. A part of the Original Music Hall building can be seen on the right.