Miller’s Dams on the Weirs Channel

“In 1718 the provincial legislature of NH had authorized owners to erect their dams and to improve ponds to their best advantage without molestation. This principle had not been modified when the Mill Act of 1868 authorized any person or company to erect dams and regulate the flow of water. Only in 1921 was the erection of a dam made subject to a finding by the Public Service commission that it would be of public use and benefit.” (From Fifty Years of Service – The History of PSNH, by Dr. Everett B. Sackett, 1976.) This is what allowed the numerous dams and mills to be constructed all along the Winnipesaukee River, from the Weirs down to Franklin. The first Laconia dam was built in 1766, the first Lakeport dam in 1781, and the first Weirs dam circa 1798. Read on for the story of these dams.

“First to appear in the 1760s and 1770s were saw mills and grist mills where dams with water-power wheels could be built. In the early 1800s, these were joined by processing mills for “carding” (combing) flax and wool, for “fulling”(cleaning, tightening, and pressing) wool, and for pressing linen. These processing mills served home spinners and weavers of woolen cloth and linen, who would sew the processed materials into shirts, tablecloths, napkins, and other goods. After around 1815, new mill factories made finished products – various items of clothing, blankets, and carpets.” (From “Stories in the History of New Hampshire’s Lakes Region”, by Daniel Heyduk, 2017.)

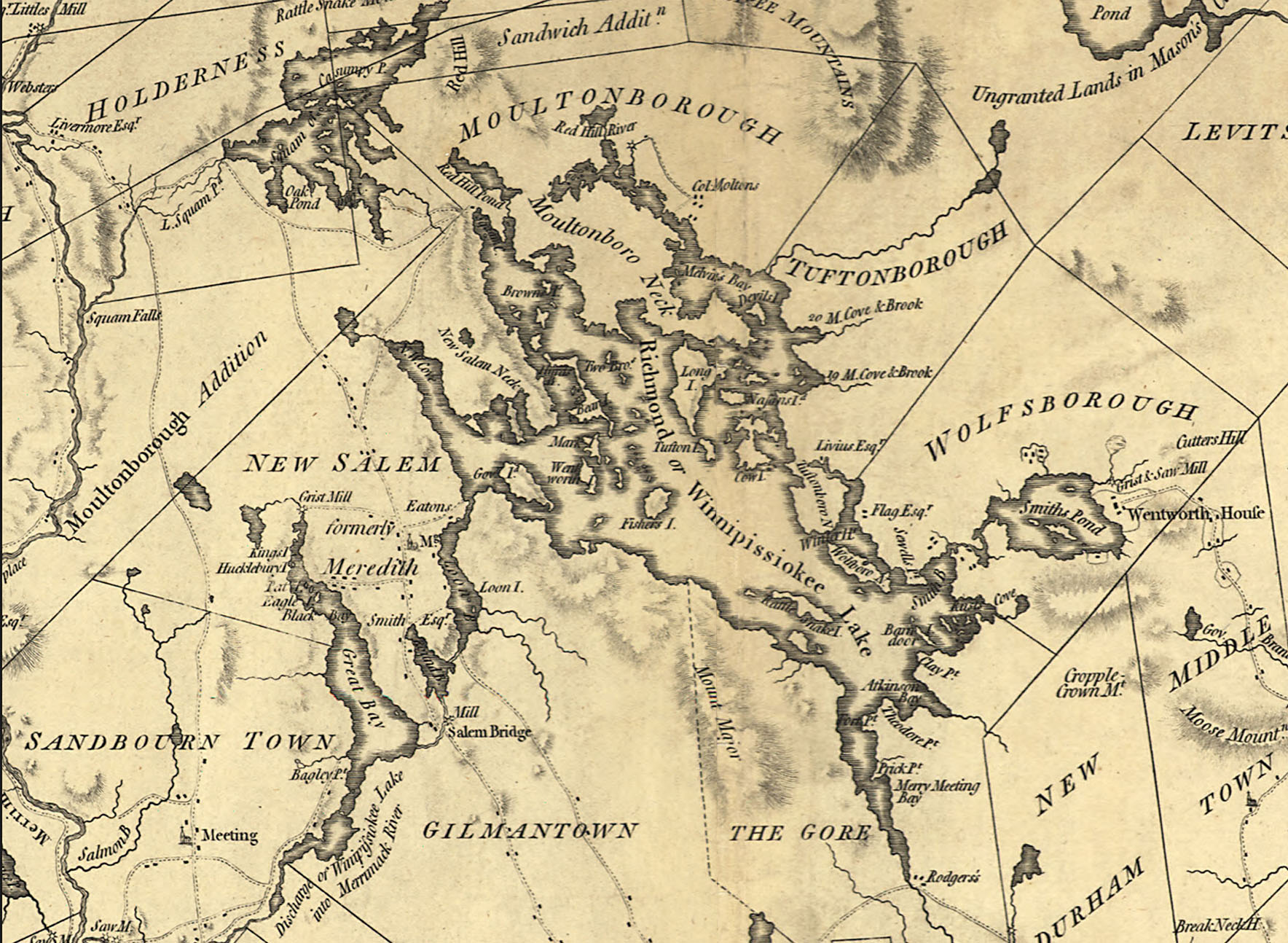

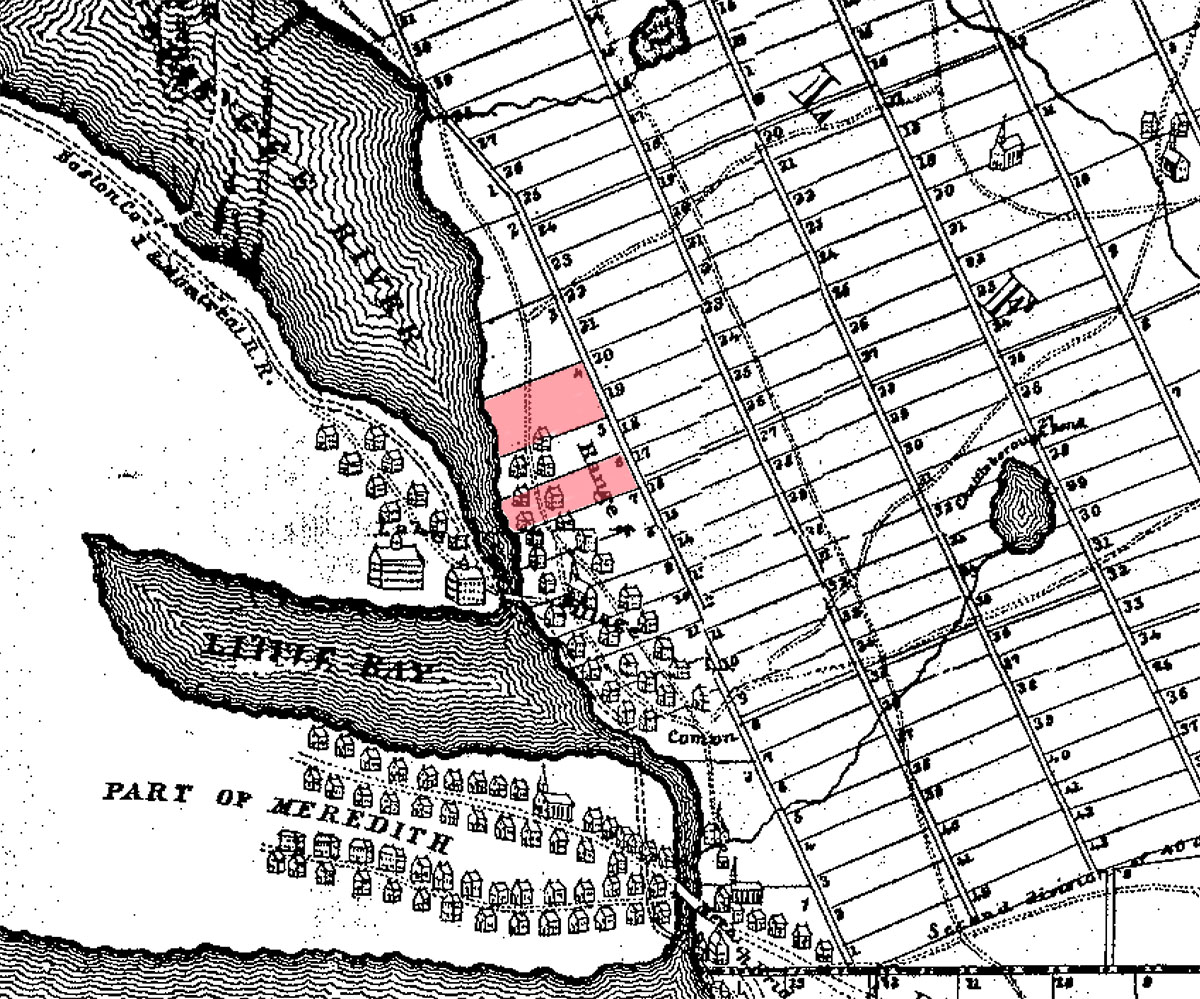

Detail from a 1784 map of Provincial New Hampshire by Samuel Holland. This is the earliest known detailed map of the Lake Winnipesaukee area. The map was actually surveyed in 1774, 10 years earlier than its publication. The only Winnipesaukee River mill marked on the map was the one at “Salem Bridge” (Laconia).

The First Laconia Dam

Before the City of Laconia split off from Meredith, taking the area of Weirs Beach with it, the western side of the Weirs channel belonged to New Salem (an early name for Meredith*), while the eastern side belonged to Gilmanton. The current voting ward map of Laconia still maintains this dichotomy, with voters who live on the western side of the channel voting in Ward 1, and voters on the eastern side voting in Ward 6.

The first mill in New Salem was not built in the Weirs channel. Rather, it was built in what is now downtown Laconia. The following information comes from Rudy Van Veghten’s 2024 book, “Ebenezer Smith, Meredith’s Prime Mover”.

On September 20, 1762, the proprietors of New Salem appointed Ebenezer Smith to a committee to “…cut a good passable road either from Gilmanton or Canterbury to the Center Square* in New Salem…”. At the same time, the town proprietors authorized construction of a sawmill. On January 3, 1763, the proprietors further instructed the committee to “…clear a good a cart road from Gilmanton Road to the Saw Mill grant in New Salem.” Between the road and the mill projects, the road directive was logically the top priority, and it appears a rough horse path was completed by the summer of 1763. However, the new road only reached the Winnipesaukee River, it did not yet cross it. On January 2, 1764, the proprietors voted that “…there be a bridge built over Winnipesaukee River at the Saw Mill grant, within twenty month from this date.” The bridge was completed during the summer of 1765. After the town’s incorporation a few years later, the bridge became known as Meredith Bridge. On the above map, it is labeled the Salem bridge. This first bridge stood for about 45 years and was replaced around 1810.

Once the road and bridge were in place, the next step was to build the sawmill. On October 7, 1765, the proprietors voted that the committee “…shall employ a sufficient number of men to build said mill in a fortnight…they will go the 22nd day of this instant October.” The mill was soon completed, and in January, 1766, the proprietors voted that Ebenezer Smith and William Mead “…shall have the care and charge of the saw mill in New Salem for three years to come.” On the above map, next to the bridge, the Mill is labeled. This first mill was built on the western, Meredith Bridge side of the river. (Also on the map, at the top of Great Bay, a Grist Mill is labeled. A grist mill is a mill designed to grind grain into flour.)

For their efforts in “keeping said mill in proper repair”, Smith and Mead received one quarter of the milled lumber. The proprietors kept another quarter, so the area’s settlers only got back half of the raw logs that they delivered to the mill. On June 14, 1768, the proprietors added Jonathan Smith and Abram Folsom Jr. to the mill’s operators while extending the lease another 7 years. (This explains the “10 years” referred to in Source #2 below – the three years of the inital lease plus the seven years of the extension.) According to Hurd*, the original sawmill “did not pay”. The poorly maintained mill was carried away by a freshet (a river flood caused by heavy rain or snowmelt) in the spring of 1779.

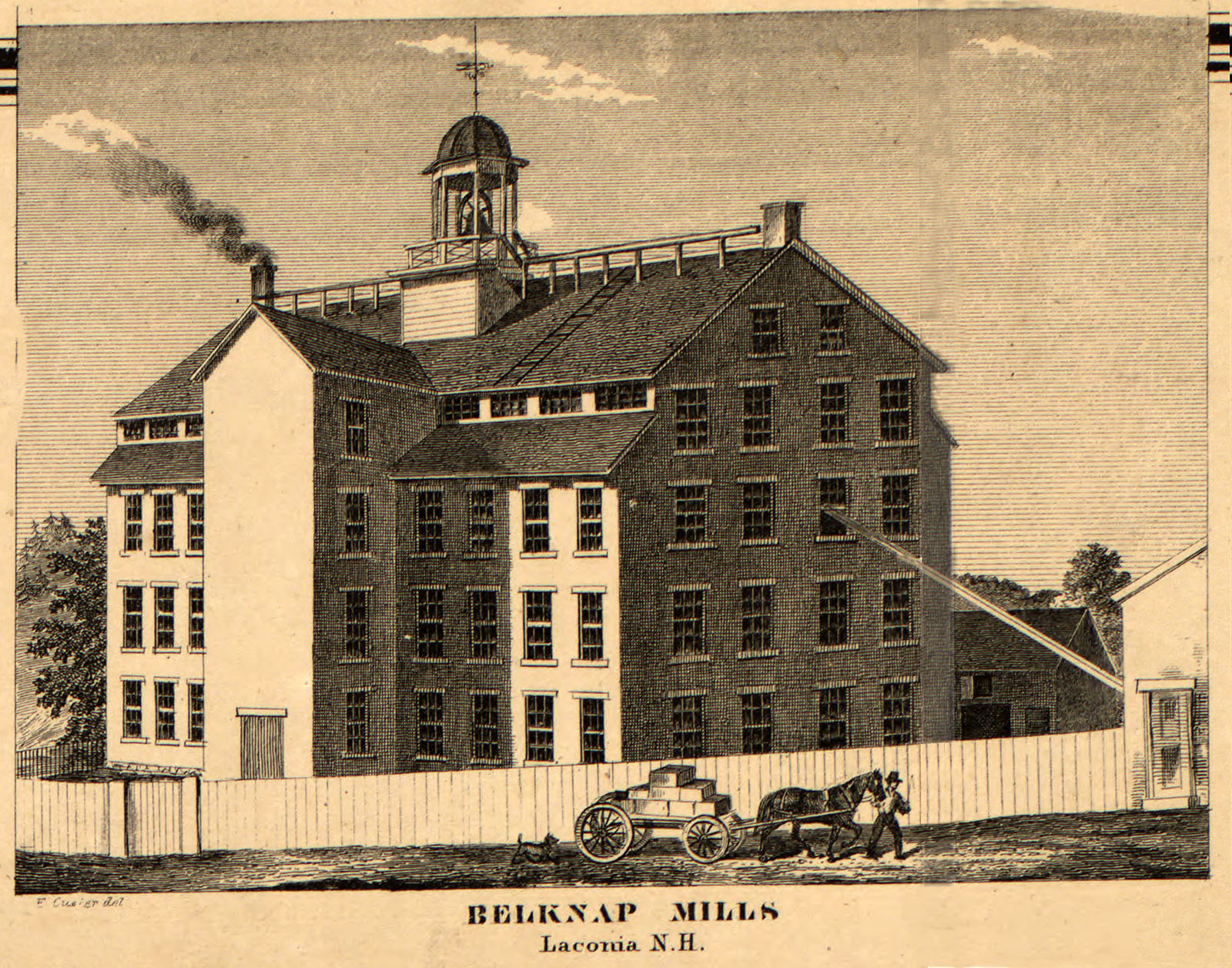

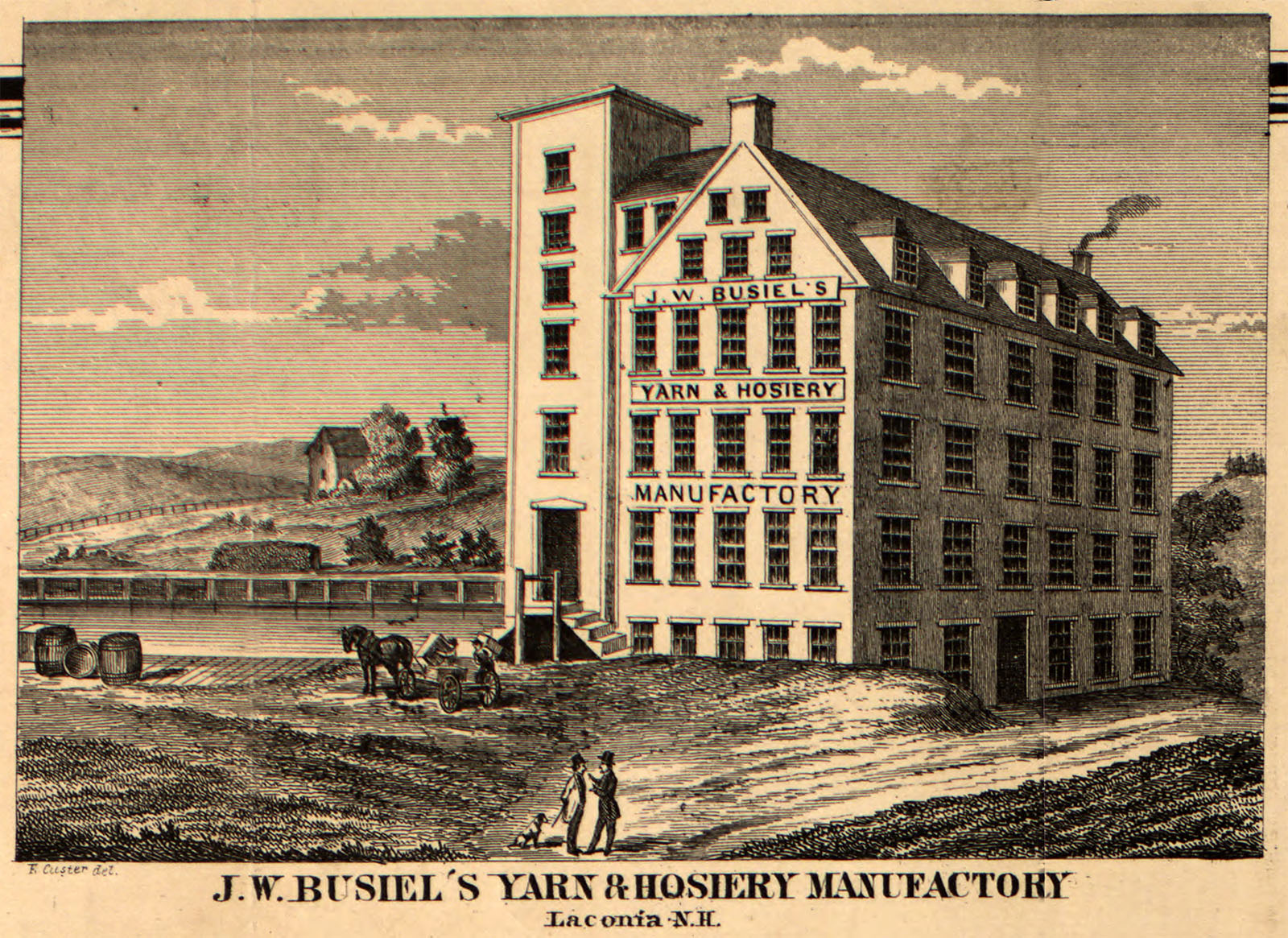

The location was still a great one for a mill operation. In 1880, Colonel Samuel Ladd bought the mill privilege and soon constructed the second mill, although this time on the eastern, Gilmanton side of the river. Many more mills followed on both sides of the river over the years.The Belknap Mill was built in 1823, the Busiel-Seeburg Mill was built in 1853 and enlarged in 1878, and the Pitman Hosiery mill was built in 1922. All three mills have been preserved.

*When the town was granted by the Masonian Proprietors on December 31, 1748, the name of Samuel Palmer was at top of the list of the original 60 grantees, hence the name of Palmer’s Town on a 1753 survey. However, in 1750, the town was formally named ‘Salem’ by the township proprietors, and this was formally changed to ‘New Salem’ by 1753, as another NH town had already taken the Salem name. On December 30, 1768, the colonial Governor of New Hampshire, John Wentworth, changed the name of the town to Meredith when it was officially incorporated, naming it after his acquaintance and political ally in Britain, Sir William Meredith. In 1778, the town asked the newly-convened New Hampshire state legislature for the name to be changed back, which is why the map maker labeled the town as “New Salem formerly Meredith”. However, the request failed to pass the legislature, and the town retained the name of Meredith.

*According to Van Veghten, the proposed “Center Square” would have been located near the intersection of today’s Parade Road and Pickerel Pond Road. Although the land on the 1/2 mile of Parade Road between Pickerel Pond Rd and Hilliard Rd is fairly flat, it is a small area at the very top of a hill that slopes off in all directions. See the map below for a drawing of the square. The settlers of Meredith found it lacking the requirements for a town center, so the square was never built, and instead the center of town arose gradually at the end of Meredith Bay. This is why Meredith lacks the town square common to most small New England towns.

*Duane Hamilton Hurd, in his History of Essex County, Massachusetts, published by J.W. Lewis and Co in Philadelphia in 1885.

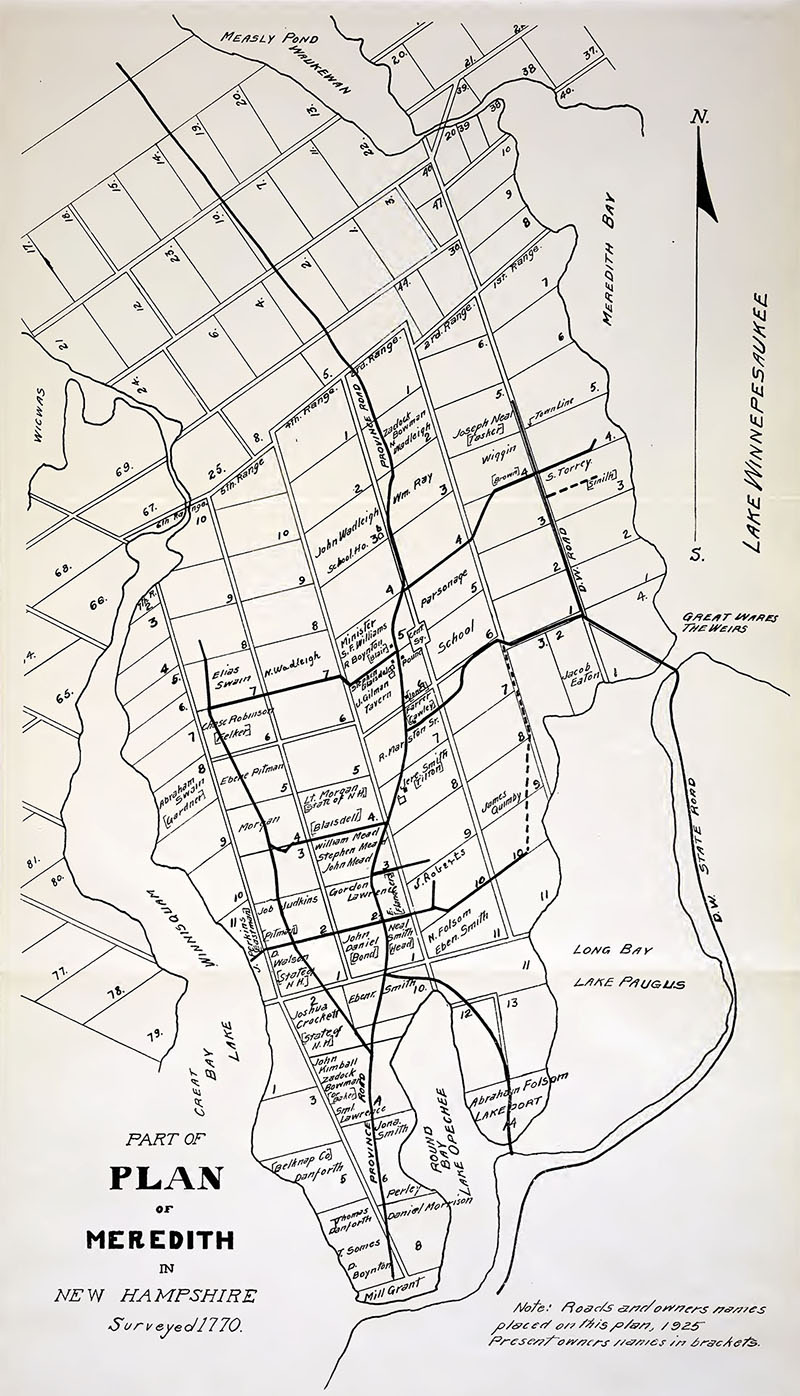

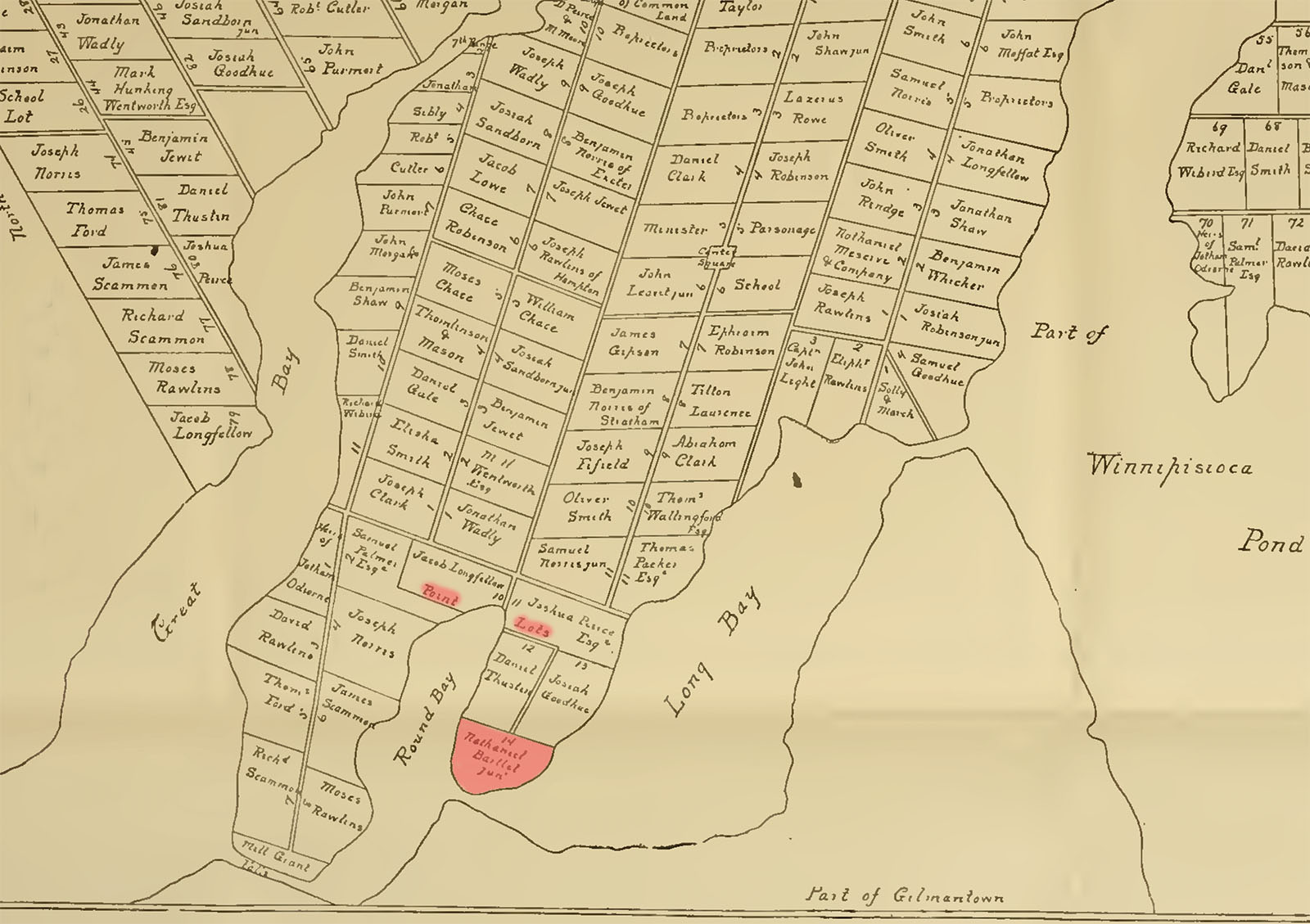

Reprint in 1925 of the 1770 surveyor’s map shows the planned Center Square, with extant 1925 roads drawn in.

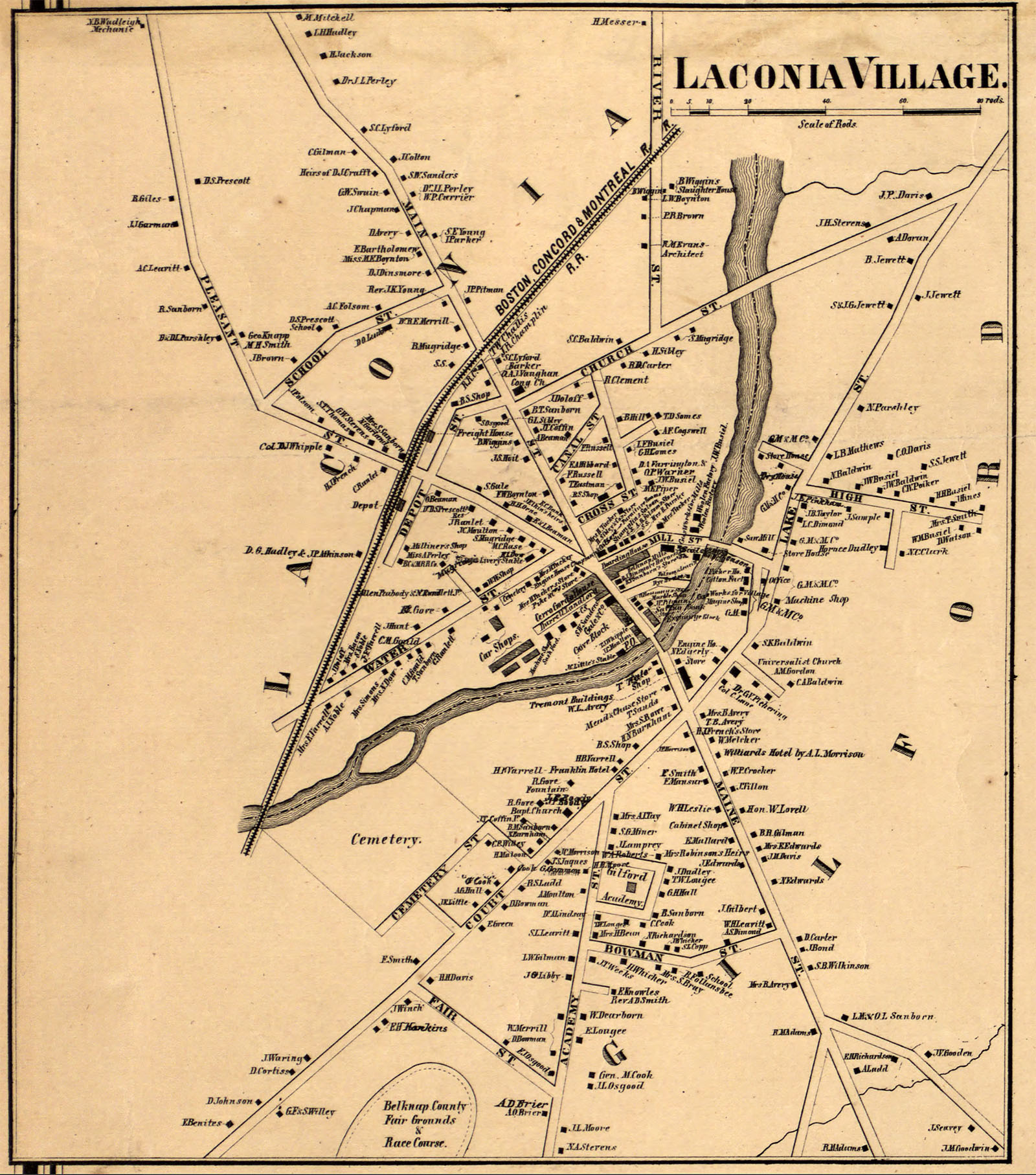

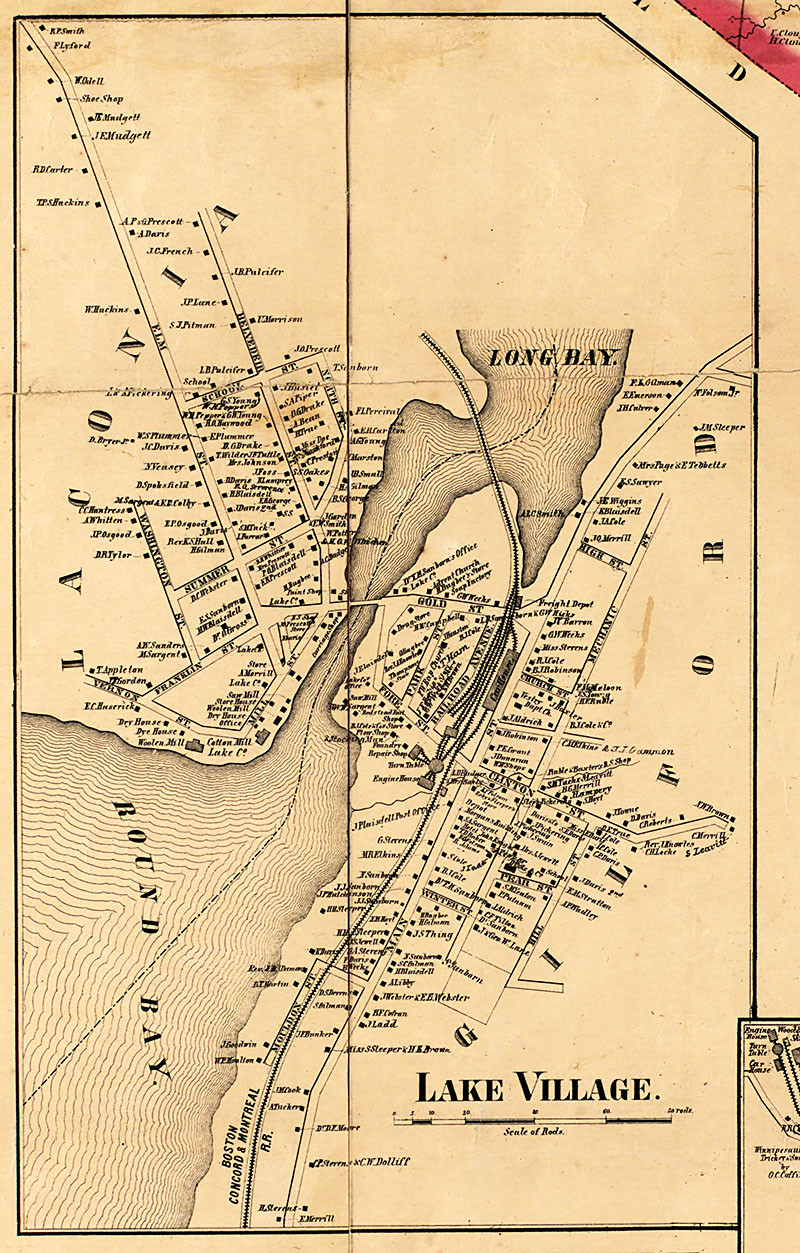

A map of Laconia Village, from an inset in an 1860 map of Belknap County, is probably the earliest detailed map of downtown Laconia available.

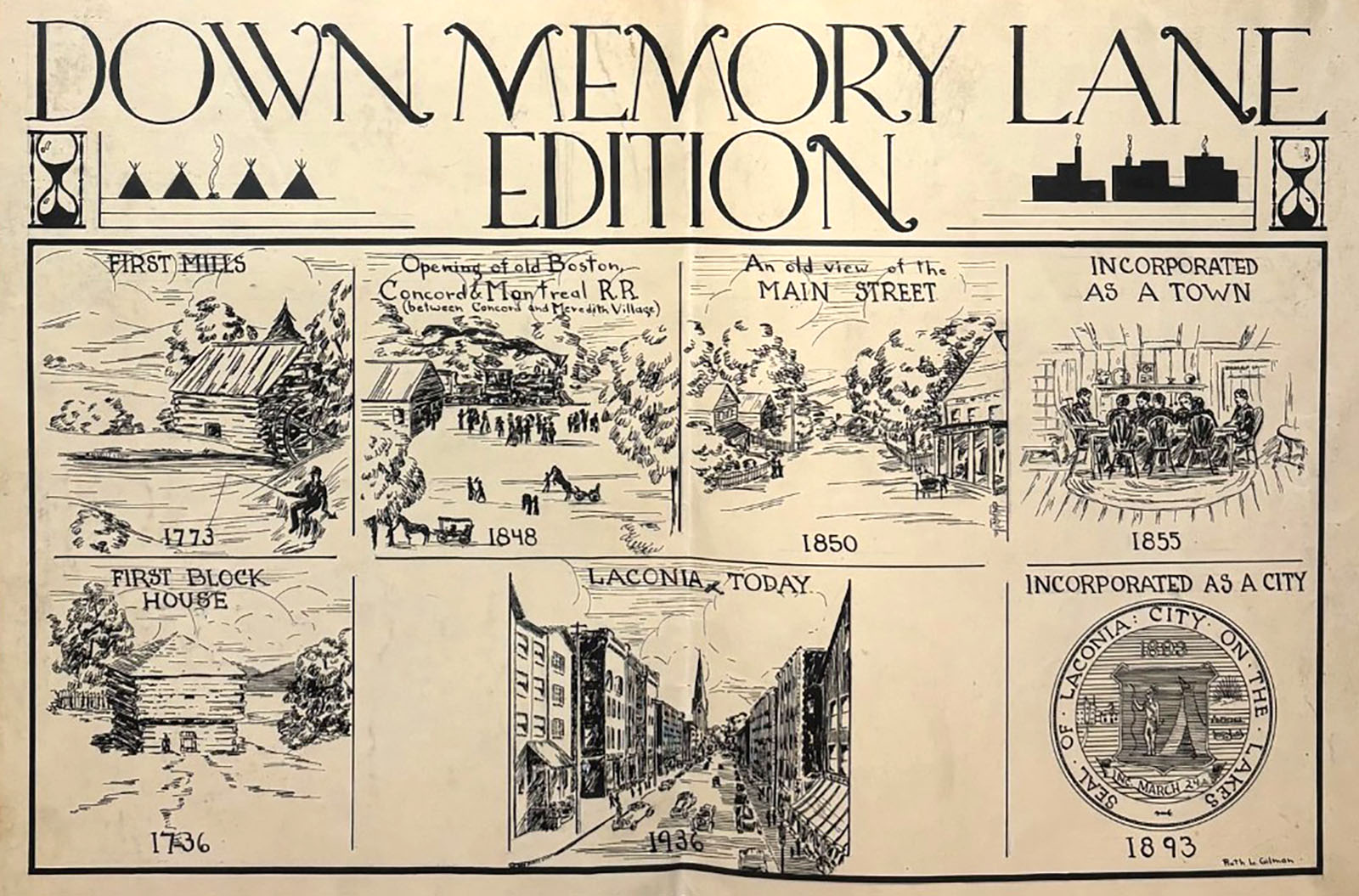

“Down Memory Lane”, cover page of the Laconia Evening Citizen, Thursday, August 27, 1936. The first mills are dated from 1773, but historic evidence is not given. This special edition was printed for the last day of the city’s Aquedoctan Celebration commemorating the 200th anniversary of the blockhouse built at the Weirs in 1736.

The First Lakeport Dam

“On May 10, 1780, the (Gilmanton) Proprietors voted that lots No. 4 and 6, in the eighth range, except 5 acres at the Wares, reserved for a mill privilege, be sold, and the money obtained for them be laid out for building Gilmanton’s part of the bridge over the river at the Wares, so far as needed, and the remainder, if any be laid out in clearing the main road from said bridge to the first Parish, and that Ebenezer Smith be the agent to sell said lots, and that the mill prvilege be given to the people in that part of town forever.” (From The History of Gilmanton, by Daniel Lancaster, published by Alfred Prescott, Gilmanton, 1845.)

On page 160 of his book, Van Veghten incorrectly ascribes the aforementioned bridge and mill to to the Weirs channel. As pointed out in Old Meredith and Vicinity, published in 1926 by the Mary Butler Chapter of the D.A.R., page 29, in the early days there were actually TWO “Wares”. The Upper Wares, also known as the Great Wares, was today’s Weirs Beach, while the Lower Wares was Lakeport. The above reference of the Gilmanton Proprietors was to the Lower Wares.

“Gilmanton’s part of the bridge” refers to the fact that the cost of the 1782 Lakeport bridge (see below) was to be split between the two towns on the opposite sides of the Winnipesaukee river – Gilmanton and Meredith. Not only the cost, but the actual construction was split up as well, with each town building their half bridges until they met in the middle. It wasn’t until an act of the NH general court on July 13, 1876, that both sides of the river became part of the same town.

Laconia’s original Church Street bridge was built in a similar fashion in 1853, with each town, Meredith and Gilford, building half of a wooden trestle bridge. The Church Street bridge was rebuilt in concrete in 1928, featuring three closed-spandrel arches. It was rebuilt again in 1981 in steel, with I-beam girders and a concrete deck.

The modern word “Weir” comes from the Old English words wær, meaning “on guard”, and wer, meaning “to dam up”. The word “Ware” in place names is both a pronunciation and written variant. The word was pluralized with the added letter “s” in reference to the Weirs and to Lakeport. In the UK, the town of Ware was named after the natural weirs in the River Lea.

It makes sense that the native Indians had other fish traps on the Winnipesaukee River besides the ones at the Weirs. Apparently, the remains of the traps in Lakeport were substantial enough to be noticed in Colonial times, but not as much as the traps at the Weirs, which were much more evident, hence the name the Great Wares.

From the map of Gilmanton drawn in 1772 by Josiah Gilman and revised in 1845. Lots No. 4 and No. 6 in Range No. 8 are shaded pink on the map. The two, 40-acre lots were located in Lakeport near the outlet of Paugus Bay. They were nowhere near the Weirs. (The houses, roads and bridges on on the map weren’t there in 1772, they were added to the map during the 1845 revision.) The 5 acres “reserved for a mill privlege …to be given to the people in that part of town forever” was undoubtedly the waterfront portion of Lot No. 6, which was the closer of the two lots to the outlet of Paugus Bay.

A detail from the 1770 plan of Meredith by surveyors Ebenezer Smith and Josiah Sanborn. Point Lot No. 14, shaded in pink, was the 100-acre homestead of Abraham Folsom V (1744-1811), the first settler of Lakeport, who settled there in 1766, clearing 10 acres for farmland, and 3 acres for a house. The lot was ideally located at the point of land between Paugus Bay and Lake Opechee, adjacent to the 8 1/2 foot, natural waterfall. In 1781, Folsom dammed the falls and built the first mills in Lakeport, a sawmill and a grist mill, just below the dam, on his side of the river. The village was then called Folsom’s Mills.

The bridge that was actually built was the Lower Wares bridge, Folsom’s Bridge in Lakeport, built in 1782. The 1782 bridge was built at Gold Street to cross the Winnipesaukee River, and is shown in the inset below from an 1860 map of Belknap County. Before the bridge was built, Abraham Folsom had already built his 1781 dam upriver of Gold Street. It was the first dam built in Lakeport.

In 1829, Nathan Batchelder and Stephen C. Lyford replaced Folsom’s dam with a 2 ½ foot higher one. Taking advantage of the greater water power, Batchelder built the Belknap (later Union Lace) hosiery mill, the Howard (later Horace Wood) cotton mill, and the Pulcifer woolen mill. For a short time, the village was known as Batchelder’s Mills. The Pulicfer mill burned down first, in 1885, while the Union and Wood mills burned down in the Great Lakeport Fire of 1903.

Circa 1850, when the village became known for the many fine steamboats being built at the local shipyard, including the jewel of Lake Winnipesaukee, the Lady of the Lake, the village became known as Lake Village.

In 1851, the Lake Company built a new dam to replace the 1829 one. The new dam was only ½ inch higher, but it was much better built, and longer. The old dam was loosely built of boulders and rubble, while the new dam was 250 feet long, and constructed of tightly mortared stone blocks.

A second crossing of the river in Lakeport was added in 1870, at Elm Street. The Elm Street bridge became the main Lakeport bridge. The Gold Street bridge became a pedestrian footbridge in the early 1900s. Both the Gold Street and Elm Street crossings are shown on the 1883 Bird’s Eye View map of Lake Village. (On the 1883 map, Elm Street is called Depot Street.)

The 1870 Elm Street bridge was wooden, and has been replaced twice with concrete bridges, first in 1914, and then again in 2003. The Elm Street bridge is currently undergoing a deck replacement in 2025. The Gold Street footbridge was replaced in 2003 with a new low truss footbridge.

In 1892, Lake Village was annexed by Laconia and renamed Lakeport. On March 24, 1893, the City of Laconia was granted its charter by the NH legislature.

Inset of Lake Village, from an 1860 Map of Belknap County, shows the Gold Street crossing.

The Weirs Dams

SOURCE #1:

The first saw mill in town was built at Weirs, in 1766, by the proprietors of the township. Ebenezer Smith and William Mead had charge of the mill, and paid rent for the same. The iron-work for this mill was brought from Exeter, and the wood-work was hewn on the spot. The power was obtained from a large under-shot wheel. The mill, although of course a rude affair, answered all purposes and remained in use for many years. For the first ten years after the mill was built the logs were sawed on the “halves” plan, and one-quarter went to the owners of the mill for rent.

From History of Merrimack and Belknap Counties, New Hampshire, by D. Hamilton Hurd, J.W. Lewis & Co., Philadelphia, 1885. Quote appears in the History of Laconia chapter on page 810.

INCORRECT. The 1766 saw mill was not built at the Weirs. It was built in downtown Laconia, which was part of “New Salem” (Meredith), at that time. See above.

SOURCE #2:

The first sawmill was built upon the Weirs channel, at the outlet of the lake, but was soon removed to the lower part of the town, as the water power was better there. After a few years it was carried away by a freshet and was rebuilt on the Gilmanton, now Gilford side of the river. At a meeting January 6, 1766, it was voted that Ebenezer Smith and William Mead have charge of the sawmill for the next three years, and that they shall saw logs to the halves for any of the proprietors in said town who shall bring logs upon the stage of the mill.

From Meredith Annals and Genealogies, Arranged by Mary. E. Neal Hanaford, Rumford Press, Concord, 1932

INCORRECT AGAIN. The 1766 saw mill was not built at the Weirs. It was built in downtown Laconia, as explained above.

SOURCE #3:

There were also mills at the Weirs, before S.C. Lyford in 1829 spoiled the water power there by raising his dam at Lakeport. There was a mill on the Gilford side in 1803 and 1804, and a wing dam extended up into the stream. In 1819 the gearing and iron work were removed, and the mill was no longer used, and gradually went into decay. It is not known who first owned this mill. The first mill on the Meredith side at the Weirs was a saw mill built in 1828. This was Odiorne’s mill on lot No. 4 in the 1st division in Meredith.

From Aquedocatan 200th Anniversary Celebration, by Laconia Chamber of Commerce, Rumford Press., Concord, 1936

IMPRECISE. The 1770 Plan of Meredith (see map) divides Meredith into three divisions. The 1st division was the land south of a line “…from the head of Great Bay to the head of Winnipsioca Pond…” Today, that line would run from the north of Lake Winnisquam to downtown Meredith. The 1st division was further divided into seven ranges. There was a lot #4 in each of the seven ranges. The 1770 map shows that lot #4 of the 1st Division, 1st Range, granted to Jonathan Longfellow, was located halfway up Meredith Bay, nowhere near the Weirs Channel. Along the Weirs Channel, the landed was divided into four numbered lots that were not part of the seven ranges. These were known as Point Lots. Point Lot #4, at what is now Endicott Rock Park, granted to Samuel Goodhue, is where Odiorne’s mill would have been located.

SOURCE #4: In his book “Rambles About the Weirs“, Edgar H. Wilcomb gives the most complete and accurate description of mill activity on the Weirs channel.

“It is not known to the writer when the first dam was built, but it was certainly before 1803, as it is a matter of record that a gristmill and a sawmill, run by waterpower, were in operation here at that time. These mills were built and operated by Horatio Prescott, and were located on the east side of the river channel. Afterward, a second sawmill and a tannery were erected and run on the west side of the channel.”

“Then, a company was organized in Dover and a large woolen mill was established here. The company invested a large amount of money in land, buildings, and other improvements, planning to make the Weirs a great manufacturing place. A Mr. Odiorn was head of the concern and the local representative. The old dam was rebuilt, much higher than before, mill buildings were erected, and machinery installed. At this time, besides the two sawmills, gristmill and tannery previously mentioned, there was an oilcloth manufactory, a hat factory, three stores, three blacksmith shops, a cooper shop, and two taverns.”

“But the Weirs was not destined to remain a manufacturing center. When Odiorn’s woolen company raised the height of the dam and held back the waters of the lake from points below, the owners of the power privilege at what is now Lakeport retaliated. They raised the height of their dam, temporarily stopping all flow below that point, and thereby causing a backup of water that effectually clogged the wheels at the Weirs. As a result, all the Weirs mills had to suspend operations. Lawsuits were instituted for recovery of damages and eminent counsel was retained, including Franklin Pierce and John P. Hale. But the suits did not come to trial, for the reason that Mr. Odiorn, the company’s head, died soon after the suits were started.”

“Not long afterward an onslaught (a flood) was made on the Weirs dam and a large section tore out. The dam was never repaired and gradually went to pieces, and thenceforth the water was allowed to run free. Finally, the present water-power company secured control and rights of flowage and the natural obstructions in the channnel were removed to such an extent that the difference in level of the water above and below the channel was very slight, and as later improvements have been made has lessened even more.” (Of course, today, there is no difference in level between the Lake and Paugus Bay.)

“Remains of these old mills and millsites may still be found, generally along the banks of small streams, remote from main channels of travel, some entirely gone except the dams, penstocks, wheel-pits and stonework of the mill foundations, others with walls partly standing, with roofs and floors decayed or destroyed, now showing grim and sentinel-like, as if in defiance of the lapse of time, and as if protesting against the march of progress which has left them desolate in its wake.”

SOURCE #5: Solon B. Colby described the very first Weirs mill, built by Horatio Prescott circa 1798, as follows:

“The mill was a crude affair with a hewn log frame and all the parts such as the log carriage, sawgate, pitman, waterwheel, etc., of hewn logs or hand-sawed boards or planks, being planed by hand labor when necessary. The waterwheel was undershot, about sixteen feet in diameter, and turned very slowly, because the current in the channel didn’t push it fast enough. In order to speed it up and increase its power, the following summer, when the water was low, a wing dam was extended diagonally up the channel a hundred feet or more to divert the water from the center of the channel to the large undershot wheel. The wing dam was built like a stone wall with stones gathered from the channel bottom. When completed, the dam was about two feet thick, two and one half feet high, and over one hundred feet in length.”

SOURCE #6:“The great river, Winnipiseogee, has, or had, three places of power: At the Weirs, or Prescott’s Mills, by wing-dams, three feet of head was utilized; but flowage has ruined the privilege and it has long been in disuse. At Lake Village, a single head of twenty feet gives great power, and it has, from the first, been well used. The Lower Falls, at Laconia, has also a single head of some greater height. The current, however, is not quite all utilized, the river proper being here nearly a mile in length from bog to bog, in the natural state, or level.”

“There were two mills at the Weirs—one on either side of the river. The Prescott Mill there gave name to the place for a time, as it was currently denominated “Prescott’s Mills” as well as Weirs. The head was so slight at this point that the power was small, notwithstanding the great volume of supply of water and its being constant; hence the privilege was considered as unimprovable and of little value, so that it naturally fell into disuse, and later, the heightening of the dam at Lake Village destroyed the privilege altogether, and so both mills ceased long ago.”

From the chapter, “History of Gilford” by Reverend J.P. Watson. The chapter is in the History of Merrimack and Belknap Counties, New Hampshire, by D. Hamilton Hurd, J.W. Lewis & Co., Philadelphia, 1885

SOURCE #7: “The Nelson Dam at the Weirs, where there had been a fall of about four feet, was flooded out by the 1829 dam at Lakeport and was removed in 1832. When the Nelson Dam was removed, some clearing of rocks was done above and below the Weirs bridge, and in 1834, the channel was deepened by about 18 inches. The channel was excavated in 1847, and again in 1881 and 1882.”

From a September 10, 1962 letter to the editor of the Laconia Evening Citizen, from William K. Stratton, manager of the Central Division of PSNH.

The Shad Path (Hilliard Road)

One year there was a scarcity of food, and Priest Folsom was talking in church, when someone entered and said, “The shad have come. The shad have come.” Priest Folsom said, “The shad have come. I close my sermon. They will do you more good than my talk.” The fish were coming upstream at the Weirs, and the inhabitants needed the fish for food, so the men all rushed down the “Shad Path,” now called the “Roller Coaster Road.”* (From History of Merrimack and Belknap Counties, New Hampshire, by D. Hamilton Hurd, J.W. Lewis & Co., Philadelphia, 1885.)

NOTES: The minister was Nicholas Carr Folsom (1747-1830), and the church was the first Baptist church in Meredith. Folsom was the Reverend of the church from 1782, when he was ordained, to circa 1800. A small icon of Folsom’s church is drawn on the 1784 Provincial Map of New Hampshire, above. The icon is just above the letter “H” in the word “Meredith”. The church was located about halfway up the hill between between what is now the Elm Street-Parade Road intersection and the Hilliard Road-Parade Road intersection. (On the 1770 survey of Meredith map, it was on Lot #8 in the Fourth Range of the First Division.) In the early 1800s, Folsom’s church burned, and a replacement church known as the “Old Daygun” was built near the town line (p.41, Carl F. Blaisdell, “Meredith Parade”). This 2nd church was later moved to North Street in Lakeport circa 1844, where it became known as North Church. Its congregation was of the Advent denomination. The church burned in the Great Lakeport Fire of 1903.

Isaac Farrar’s tavern and store was built near Folsom’s church. The tavern was located where the Petal Pushers plant nursery is today, at the top of Hilliard Road. Farrar “kept tavern” there until 1860 (pgs 45-46, the D.A.R. book.)

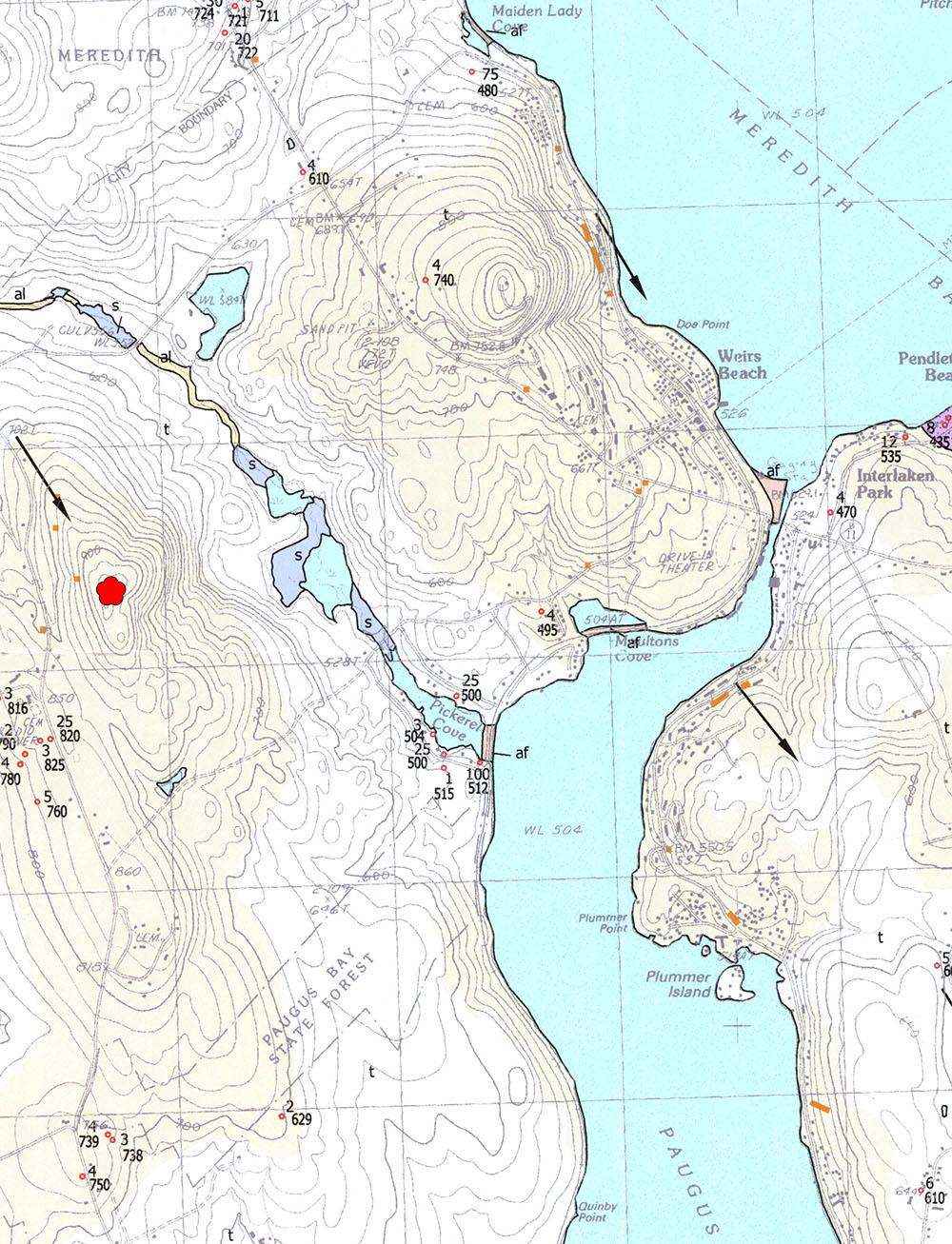

*The Shad Path was not Roller Coaster Road. Roller Coaster Road ends over 1 mile away from the Channel, on the opposite side of Brickyard Mountain. The Shad Path was laid out on March 1, 1770, and was 576 rods (1.8 miles) long. It is now called Hillard Road, which descends from Parade Road (formerly Province Road), down to the top of Tower Hill, very near the Weirs Channel. Currently, only the lower half of Hilliard Road is paved and maintained. The upper half of Hilliard Road, from Parade Road down to Pickerel Cove, is a very rough path, closed to vehicles.

Wilcomb called the Shad Path the Cross Road, and described it this way: “The old Cross Road, extending southward, leads down and up steep sides of a wide, broken valley, that should not be attempted by auto. This is a picturesque region, comprised of small hilly farms and summer residences along the shores of of the lake, and forest-clad, rock-bound hills, with tumbled aspects, farther back, interesting to lovers of wild scenery. Two considerable arms of the lower lake still extend into this valley and are known as North Cove and South Cove, into each of which flow good-sized streams of water, especially the one emptying into South Cove.”

The smaller, northern cove is now called Moultons Cove. The City of Laconia’s tax map for some unknown reason still shows it as Chattle Cove, after one of the early settlers. However, Moultons Cove is the name seen everywhere now, on maps of Lake Winnipesaukee and other area maps.

Today, we call the southern cove Pickerel Cove. Wilcomb said that the cove was “considered about the best pickerel fishing-place in the entire lake region. Bobbing through the ice in the winter, we would sometimes take out a bushel basketfull at a time. The family once registered the weight of a monster pickerel at sixteen pounds.” A considerable wetland flows into Pickerel Cove. Wilcomb called the wetland flow into Pickerel Cove the “Mad River”, but it is really just a large stream. There is a short unmarked trail off Hillard Road that flanks the southern shore of this wetland.

Wilcomb’s family farm was on the north side of Pickerel Cove. On the opposite, southern side of the cove, was the old “Gordonville Settlement”, “…consisting of numerous cellars and stone foundations of former dwellinghouses, the old milldam and millpond that became a big meadow after the dam gave way and the water was drained off. This is where Captain Gordon and his son, the ‘Squire’, had a big sawmill for many years. There is still a fairly good water-power available here, out of use for nearly a century.”

Wilcomb continued, “Back of the millpond is rough-ribbed, granite-faced Raccoon Mountain, whose precipitous ledges defy ascent of all but the most venturesome of sightseers. Hidden for ages by the woody growths and little known, it is a rough, wild section of tumbled rocks and ledges that is well worth visiting, inspecting and picturing by means of camera or paint brush, particularly the lofty precipices, the equal of which are not know to exist anywhere in the lake region.”

Wilcomb may have been exaggerating. Today, there is no mountain named Raccoon Mountain in this vicinity. However, there is a distinct high spot on topographical maps, about halfway between Roller Coaster Road and Hilliard Road, that is equal in height to Brickyard Mountain, and similarly has a steep drop-off on its southeastern flank*. Today that high spot is completely wooded, but back in Wilcomb’s day it may have been cleared off.

Note: Instead of Roller Coaster Road, Wilcomb described the road that is “west of but parallel with Cross Road” as Robinson Road. The Robinson graveyard is a short distance into the woods on the east side of Parade Road, just before the turn off to Roller Coaster road. Buried here are Nathaniel Robinson, one of the first settlers in the area, who fought in the French and Indian war, and his son Joseph Robinson, who fought in the Revolutionary War.

*As the mile-high ice sheet from the last Ice Age retreated from the Lakes Region about 14,500 years ago, it piled debris on the northwest sides of the local hills and mountains, while leaving many of them with steep southeast faces. Other local examples of this geological action include Hersey Mountain in Sanbornton, Ladd Mountain in Meredith, and Crockett’s Ledge in Meredith.

The possible location of “Raccoon Mountain” as described by Wilcomb is indicated with the red star on this detail from the Laconia Quadrangle of the US Geological Survey.

Biography of Edgar H. Wilcomb

A biography of Edgar H. Wilcomb is deserved here for the many attributions to Wilcomb on this website. He was one of only four local historians to concentrate on the Weirs or Weirs Beach. The others were artist J. Warren Thyng (1841-1927); Warren Huse, columnist for the Laconia Daily Sun; and myself, Robert Ames, webmaster of this website. I personally have a lot in common with Wilcomb. We both grew up in the Weirs, lived in California for some years (myself in Berkeley, CA, from 1978-1980), then moved back east to Massachusetts (myself to Boston, Cambridge, and Brookline, before eventually setting down in Newton, MA.)

In 1923, Wilcomb published his series of booklets called “Winnipesaukee Lake Country Gleanings”. Five booklets were published in Worcester. The first two booklets, A-1, “Rambles About The Weirs”, and B-1, “Local Stories and Personal Reminiscences of the Days of Long Ago”, were combined together; the combined booklet can be read in its entirety here. His third booklet, D-1, “The Lakeport Cleft and Great Prehistoric Dam”, can also be read online. His fourth booklet, E-1, “Old Davisville and Governor’s Island”, and fifth booklet, F-1, “Ancient Aquedocatan”, are not yet available online, but can found at the Laconia Public Library. Two other Wilcomb booklets, C-1, about Gilford, and G-1, about Meredith, were supposedly published, but cannot be located anywhere.

Wilcomb’s writing could be quite entertaining. As Wilcomb wrote about his own style, “Convinced that the usual manner of treating historical subjects is considered dry and uninteresting, I am endeavoring to write in a light, sketchy, narrative style, retaining all the essential historical facts, however.”

Covers of Wilcomb booklets A-1 & B-1, D-1, E-1, and F-1. The booklet covers were illustrated with sketches of Indian activity, a view of the lake, and the New Hotel Weirs.

Wilcomb planned to release other booklets about Gilford, Meredith, and other Winnipesaukee communities, and advertised them in advance in his five known booklets, but apparently none of these additional booklets were ever completed, for unknown reason. Wilcomb died April 7, 1929, at age 73,and is buried in Laconia’s Bayside Cemetary on Union Avenue.

A partial biography of Wilcomb comes from the book “Genealogy of the Willcomb Family of New England 1655-1902“. The book has bios of Wilcomb; his father Francis; his brothers J. Frank, Charles, and Owen; and his great-grandfather Moses. The genealogy book only tracks Edgar to the year 1902, when he was a middle-aged businessman living in Worcester, MA. Below are the bios of Wilcomb and his immediate family from the genealogy book.

Regarding his brother Charles, Wilcomb writes, “…my collection of curios (particularly Indian relics) I turned over to my brother Charles, who made it a life work, resulting in his becoming curator of the Golden Gate Park museum in San Francisco (now known as the de Young museum), which he was chiefly instrumental in establishing, after which he assisted in a similar manner in establishing the Municipal Museum in Oakland, Cal., of which he was curator until his death. Both of these museums contain many Indian relics and other articles gathered by us in the Winnipesaukee lake region.”