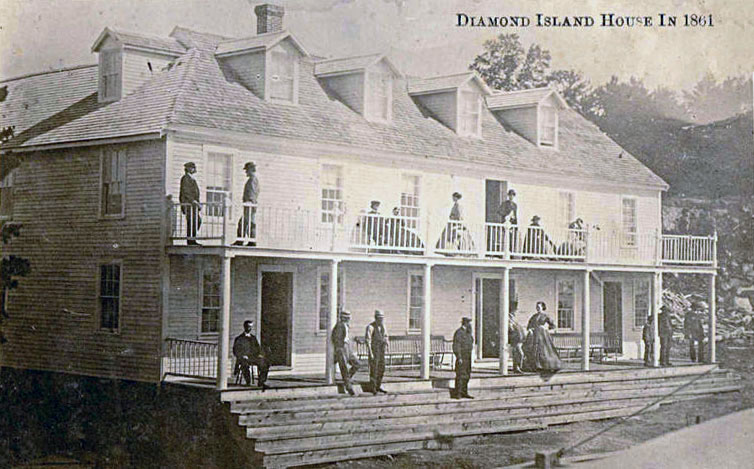

Diamond Island House

1861

The Diamond Island house in 1861. It is hard to believe that this simple structure ultimately became the New Hotel Weirs. However, a common element are the verandas that run the entire length of the building, as well as the numerous dormers along the roof line. Note the Lady of the Lake docked in front of the Diamond Island House. This was the predominant mode of transportation to the house.

The Diamond Island house in 1861. Postcard #2. On the reverse, the following words were hand-written: “Moved over the ice to the Weirs – no longer exists. Used timbers to build right-hand section of Hotel Weirs. First called Sanborn’s House, then the Weirs Hotel. Enlarged before 1909, second Tower and wing were added and name changed to the New Hotel Weirs. Burned 1924 – 230 rooms.”

Below, a photo of the Lady of the Lake at the Diamond Island House. One of the Lady’s regular stops was at Diamond Island. Coincidentally, the name of the island matched the diamond the Lady sported on her paddlewheel box.

The Winnipesaukee Steamboat Company, owners of the Lady, had purchased Diamond Island in 1865 after leasing it for four years from Nathaniel Folsom of Wolfeboro. They had built the Diamond Island House in 1861 to provide a rest stop for their tourist passengers. The company then further developed the hotel, adding an ice house, bowling alley, and even a dance hall. The House became a very popular hostelry for Civil War-era summer excursionists. The hotel was open year-round, catering to winter fishermen in the off-season. How it was supplied in the winter, when it was socked in by the winter ice and unreachable by the Lady, is unknown.

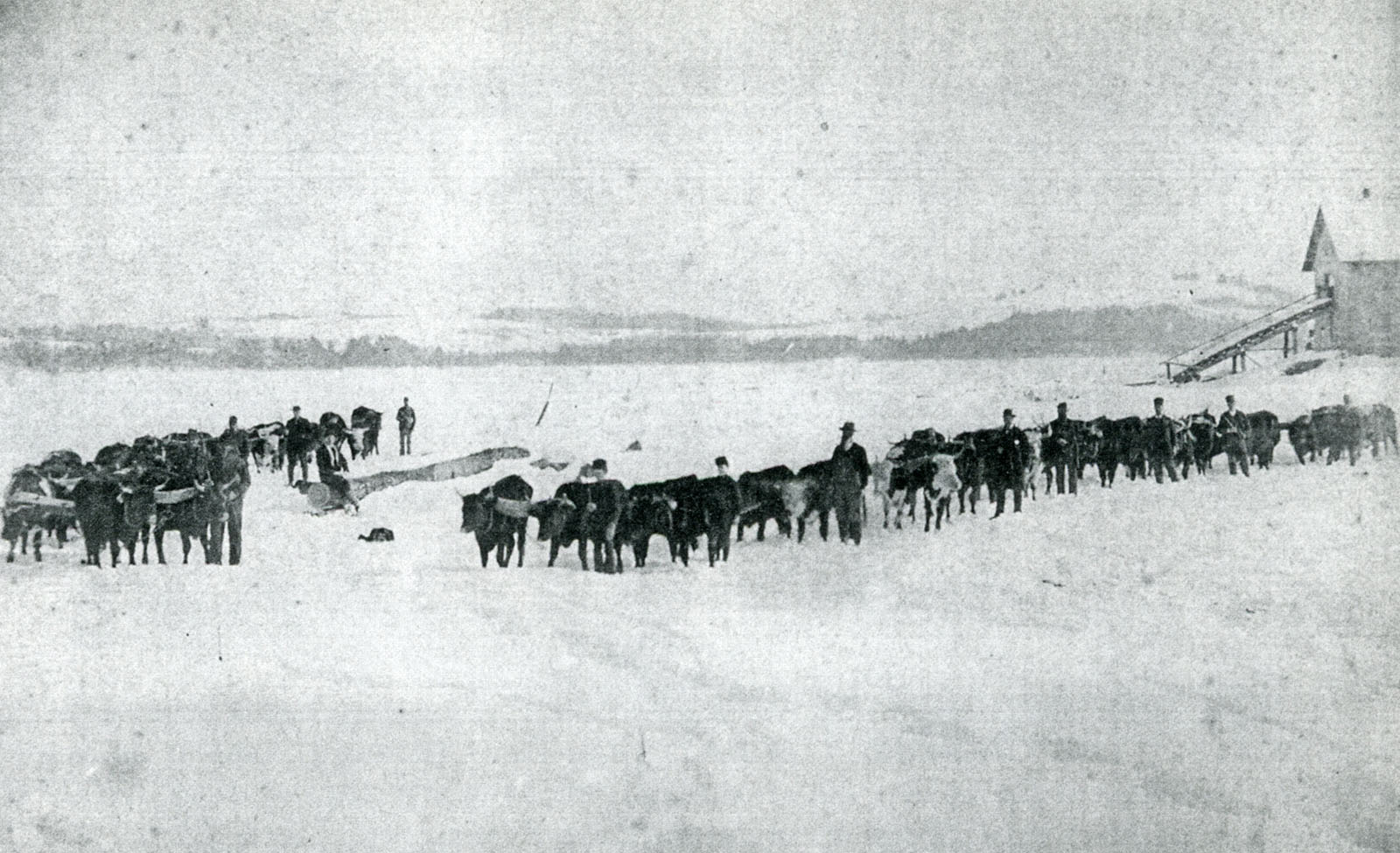

In the 1870s, the hotel developed an unsavory reputation as a rum house and gambling den. As a result, when the steamboat company sold the island in 1880 to Winborn A. Sanborn, a former captain of the Lady, he did not hesitate to dismantle the house. In February, 1880, he had the hotel cut in half. A team of 16 yoked oxen hauled the halves over the ice to Weirs Beach. There, he reassembled the halves to build the Sanborn House. Only two years later, Sanborn died. The hotel was then renamed the Hotel Weirs.

D. Hamilton Hurd, in his “History of Merrimack and Belknap Counties”, wrote that it was Captain Sanborn, “…to whose energy and enterprise that the development of that beautiful summer resort, Weirs, is due. In 1880, he conceived the idea of building a hotel at the Weirs. With him to think was to act, and in six weeks from the time that sills were laid, “Hotel Weirs” was ready for occupancy.” Hurd provides a biography of Sanborn starting on page 775 of his book.

Without its hotel, Diamond Island remained relatively undeveloped until the arrival of the U.S. Navy’s “Visibility Laboratory”, from 1947-1966. A fascinating account of the laboratory can be read in Stephanie A. Erickson’s book, “Islands of Southern Lake Winnipesaukee”, pages 70-73. In 1970, the island was subdivided into 26 properties.

Moving Buildings

Moving buildings was done frequently in the Lakes Region during the nineteenth century. It was done with animal power and relatively simple equipment, and most of it was done in winter. Several things made moving buildings more attractive than dismantling them. Virtually all buildings in the area at that time were of wood post-and-beam construction, rather than brick, and they had no plumbing or wiring. The roads had no overhead power or telephone lines, and there was little traffic to impede the move. There were many local farms around with plenty of oxen. Yokes of oxen could be strung together almost without limit to pull a load. Winter roads of smooth packed snow allowed for easier transportation than at other times of the year.

To move a building, some breaks were made in the foundation so that screw jacks could be inserted under the wooden sills. The jacks were all turned at the same rate to raise the building evenly off its foundation. Beams were inserted at intervals below the bottom of the sill at right angles to the direction the building was to go, while other beams were placed under those, pointing in the direction of travel. The building was lowered onto sled runners and slid away from its foundation by the use of pulleys, ropes, and yokes of oxen. In winter, snow could be piled and frozen to level the runway from the foundation to the road. Once everything was in place, multiple yoked pairs of calm, dependable oxen were hooked to the load, and the building was moved to its new site, where a foundation was ready to receive it. The block and tackle then brought it into position, screws raised it, and the transporting beams were removed. Screws then lowered it evenly until its sills rested on the new foundation. In addtion to roads, frozen lakes were sometimes used as moving routes.

(Preceding from Daniel Heyduk’s Stories in the History of New Hampshire’s Lakes Region, pgs 57-58.)