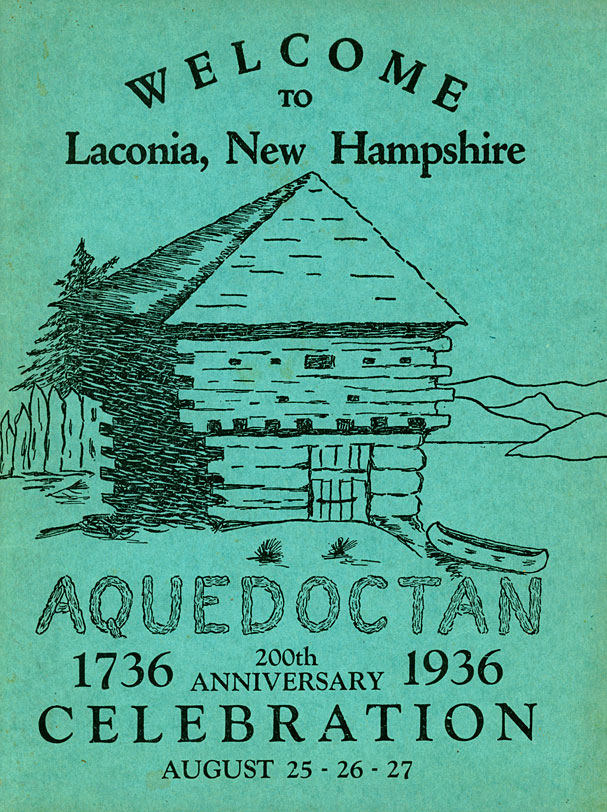

Blockhouse at Aquedoctan

On August 25-27, 1936, Laconia held a bicentennial celebration of the blockhouse fort at Aquedoctan. The fourteen-foot square fort, better known as a “blockhouse”, or garrison house, was built between June 11-25, 1736. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a blockhouse is “a structure of heavy timbers with sides loopholed and pierced for gunfire and often with a projecting upper story”.

Parades, fireworks, band concerts, horse and bicycle races, a baseball game and tennis tournament, and even a “Pioneer Ball” at Irwin’s (won by Miss Frances Samuels, a 20 year old blonde beauty, who was crowned “Miss Aquedoctan”) comprised some of the three days of festivities.

The program cover for the celebration. This 64-page souvenir program was sold for 10¢ by the Boy Scouts, with a limited number distributed to advertisers.

The only real fort (several structures surrounded by defensible walls) ever built in the Lakes Region was one built in Lochmere in 1746 by colonial militia under Colonel Atkinson of Portsmouth. It was occupied by several hundred soldiers, but after only a year or two of seeing limited action, the fort was abandoned, its stone walls being used later to build a mill.

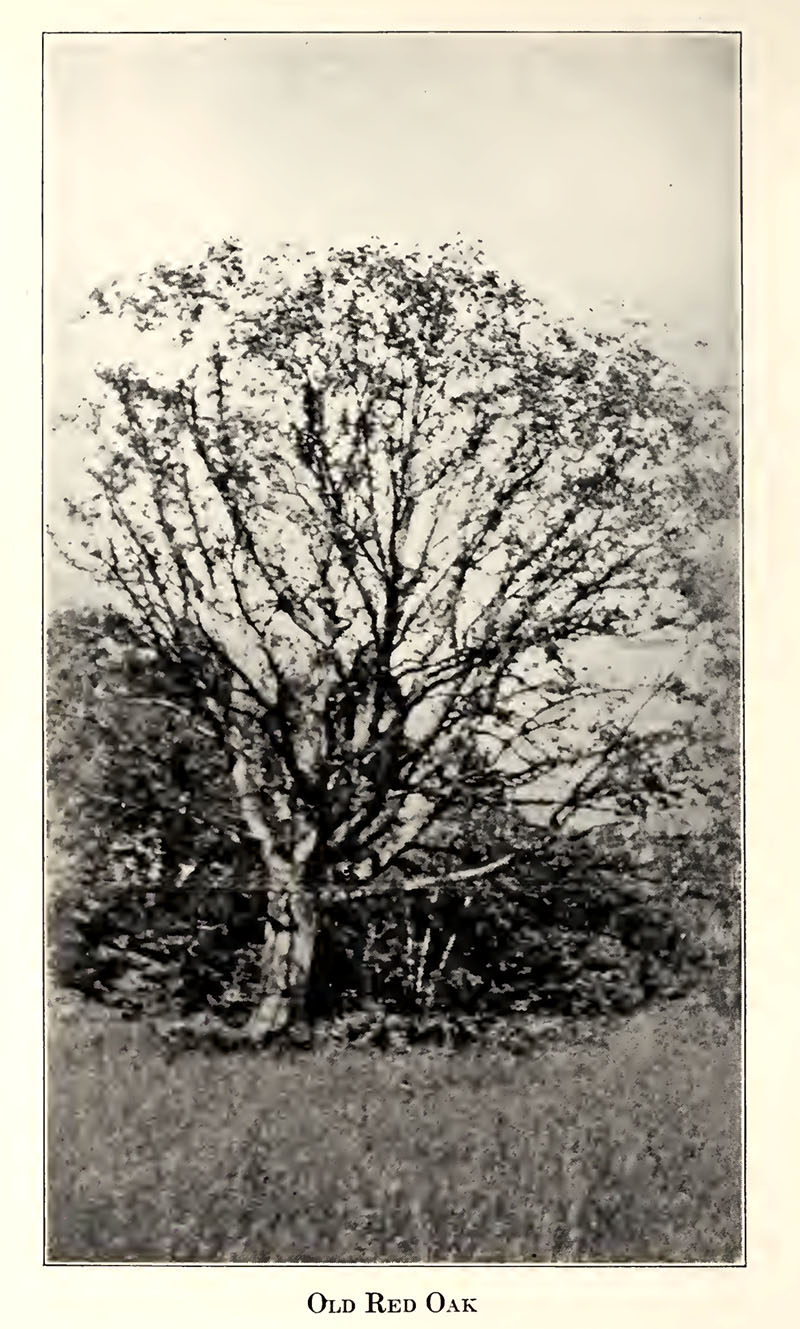

The exact location of the blockhouse on the east side of the Weirs Channel is of some controversy. Arthur H. Nighswander, writing in the Aquedoctan program, placed it “about opposite the point where Endicott Rock now is”. However, this would have put the blockhouse in a most vulnerable position, adjacent to the water. Early Gilmanton historian Daniel Lancaster located the blockhouse “nearly opposite the old oak* at the corner of White Oaks Road”, which implies it was located at the foot of the hill where White Oaks Road intersected the Gilmanton road (now 11B), about 100 yards away from the Channel. Gilford historian Arthur A. Tilton placed the blockhouse at the crest of the hill on White Oaks Road, where it would have had a commanding view of the area.

The blockhouse was not built to defend any residents of Weirs Beach, for there were none at the time. Rather, it was one of four blockhouses built by the proprietors of Gilmanton, a frontier town which had been incorporated only a few years earlier, in 1727. The town of Gilmanton at the time was much larger than it is today and included parts of present-day Gilford, Belmont, and Laconia.

Certainly the Gilmanton proprietors had much cause to be concerned for the safety and welfare of their town. In one of the most infamous recorded incidents, on March 18, 1690, Abenaki Indian Chief Wohawa, also known as Hopehood, had raided Salmon Falls (near Dover), resulting in the death of nearly thirty persons and captivity of over fifty. After another atrocity at Fox Point (near Portland) in May of 1690, Wohawa came to Weirs Beach “in the hope of enlisting the warriors at Aquadoctan into his exterminating campaign against the English settlements.” There he was killed in what appeared to be a case of mistaken identity. A war party of Abenaki Indians from Canada camping at Aquedoctan mistook Wohawa as a Mohawk, an enemy Iroquois of the Five Nations, with whom the Abenaki were then at war.

The fear was such that there was no permanent settlement made at Gilmanton until 1761, with the only visitors to town being the occassional hunter or trapper. As Lancaster wrote, “Efforts were made at different times to induce settlers to venture into this wilderness, but the dread of savage cruelties deterred them.” The dread stemmed from a series of six Anglo-Abenaki wars. The first four were: 1) King Philip’s War (1675-1678) 2) King William’s War (1688-1697) 3) Queen Ann’s War (1702-1713) and 4) Dummer’s War (1722-1727).

During the final, “two bloody wars” with the French and Indians, 5) King George’s War (1744-1748) and the 6) French and Indian War (1754-1763), Lancaster continues, “The scouting parties of French and Indians ranged the forests, and rendered the frontier settlements exceedingly dangerous…What rendered this enterprize peculiarly perilous, was that Lake Winnepisiogee on the northern boundary, was the rendezvous for the enemy’s scouting parties, as it furnished them with fishing ground when their game and plunder failed; and the adjacent Mountains became their observatory, or post of observation, whence by descrying the rising smoke in the forests they could easily learn the position for every new settler for a vast region around…Moreover for the St. Francis [Canadian] Indians, who more than any other tribe annoyed the frontier towns at that time…the route** was easy for them to the waters of the Winnipesiogee.”

In conclusion, while the blockhouse was constructed to defend Gilmanton settlers, there were no settlers until after the Indian threat had passed, so it is unknown whether the blockhouse was ever actually used for defensive purposes against Indian attack.

Edgar H. Wilcomb, in his booklet “Ancient Aquadoctan”, claimed that the Indians at the Weirs were peaceful. “The one bright spot of New Hampshire Indian history was at the outlet of Lake Winnipesaukee. An unusually peaceful tribe dwelt here. Though tradition says that the Indian tribes warred much among themselves, we have no knowledge of serious difficulties here between them and the white settlers. It may be that there was a subtle influence in favor of the first few white people, for, according to tradition, there was one white man, said to be the first settler, whom the Indians regarded with mortal fear, on account of some supernatural influence which he is said to have exerted over them. Here they remained, until, reduced in numbers by frequent ravages of their jealous neighbors—the savage Ossipees to the northward and the little less troublesome Penacooks to the southward—they disappeared altogther.”

*According to the Aquedoctan program, this is the same Red Oak Tree “which figured so prominently in our early history, when, in 1738, it was ‘spotted on four sides’ to mark the starting point of the lots in the most northerly part of Gilmanton.” The tree, 75′ high and 13′ in circumference, was still standing at the “south-westerly corner of the Weirs Road leading to Gilford Station and the White Oaks Road” until just a few years before the 1936 celebration, when it was so badly decayed it had to be cut down. The program concluded, “Over two hundred years this Red Oak Tree stood ‘on guard’. It has earned its place in history and with its likeness preserved it will not be forgotten…”.

**The route referred to was known as the Asquamchumaukee Trail. It led from Meredith Neck to Squam Lake to Little Squam Lake to Plymouth, then along the Baker (Asquamchumaukee) River to Wentworth and Glencliff, then through the Oliverian Notch to Haverhill, where it crossed the Connecticut River to end in Newbury, VT. This route was used many times by raiding parties from Canada, and earlier, from Mohawk territory.

In Fort Kent, Maine, one can visit an actual blockhouse, built in 1838, that looks like an exact duplicate of the blockhouse depicted on the bicentennial celebration cover. Click here for more information about the Fort Kent blockhouse (below), a National Historic Landmark.

A photo of the interior of the historical Gilman Garrison House in Exeter, NH. This is what the inside of the blockhouse at Weirs Beach probably looked like.

The Old Red Oak

The Old Red Oak. Photo from page 52 of “Old Meredith and Vicinity“, published by the Mary Butler Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution in 1926. According to the writer, “This tree, which must have been of good size to survive spotting on four sides, is still standing…but it has died during the past year. Its branches are wide spreading and its trunk has great scars on the four sides, which, no doubt, were from wounds made by the surveyor’s axe. The picture cannot do justice to this beautiful tree, as it was taken after it had commenced to weaken with age and could not send forth its foliage with accustomed strength and vigor. Each year it has grown weaker until finally this past summer it failed to send forth even the tiniest green shoot. Over two hundred years, this Red Oak Tree has stood on guard. It has earned its place in history, and with its likeness preserved, it will not be forgotten when it has fallen by the wayside.”

The Indian Fort

There was another fort in Weirs Beach, but it was long gone by the time the colonial blockhouse was built. It was thought that there must have been an Indian fort located about where the Weirs Drive-In is today. E.P. Jewell wrote, “All of the prominent tribes had forts, constructed for defense against warlike assaults. A desirable location for the fort was carefully selected, where in case of an attack or a long siege, water could be obtained. Whatever space was required was enclosed by a strong palisade, constructed for defense. Strong and tall poles, pointed at the top, were firmly set in the ground close togethr in double rows. The structure was strengthened by smaller poles fastened on the inside, the entire length of the palisade; only a small space was left for an entrance, which could be quickly closed in case of an attack. The entrance was so ingeniously constructed, fortified and guarded that surprise or capture seemed almost impossible. Within the palisade was located a vllage of wigwams and stores of food. These forts were used as winter quarters in time of peace. Some tribes had several forts where the entire tribe could find shelter and a fair degree of comfort through the winter.”