Colonials

Why is Weirs Beach where Lake Winnipesaukee begins?

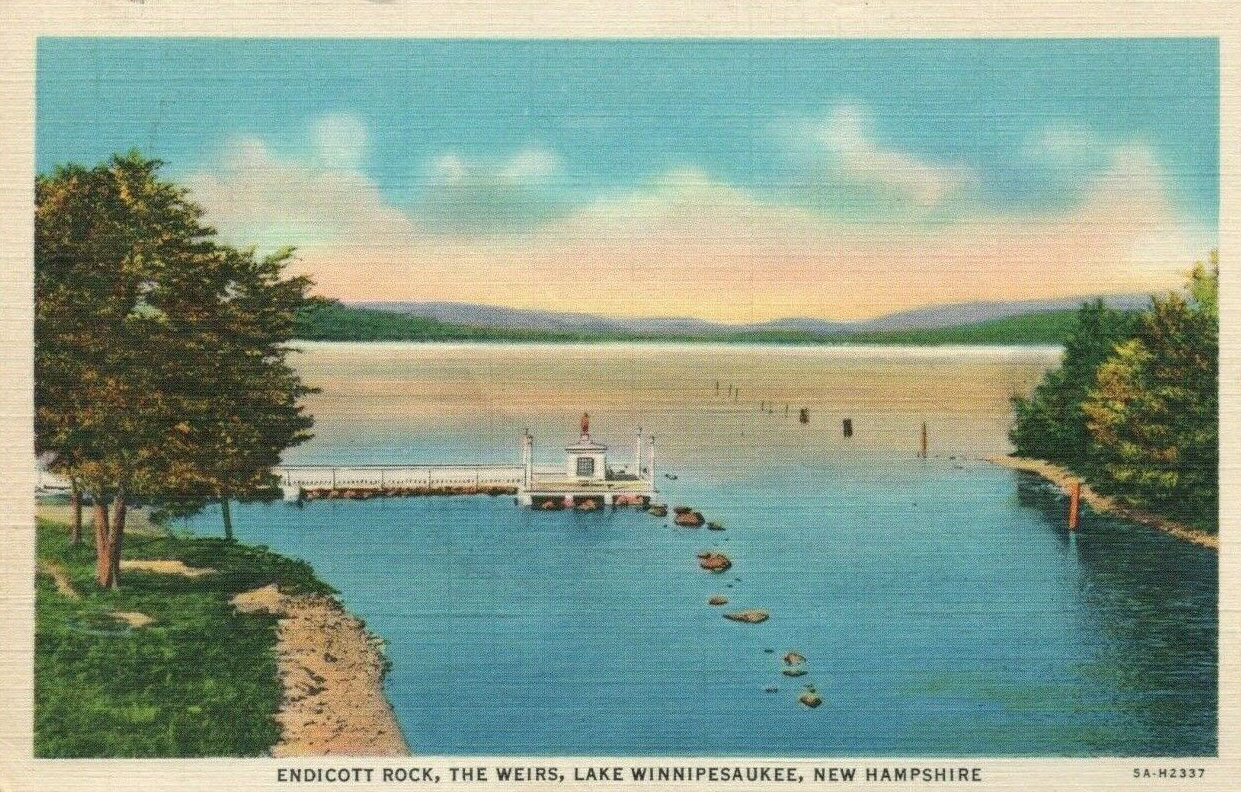

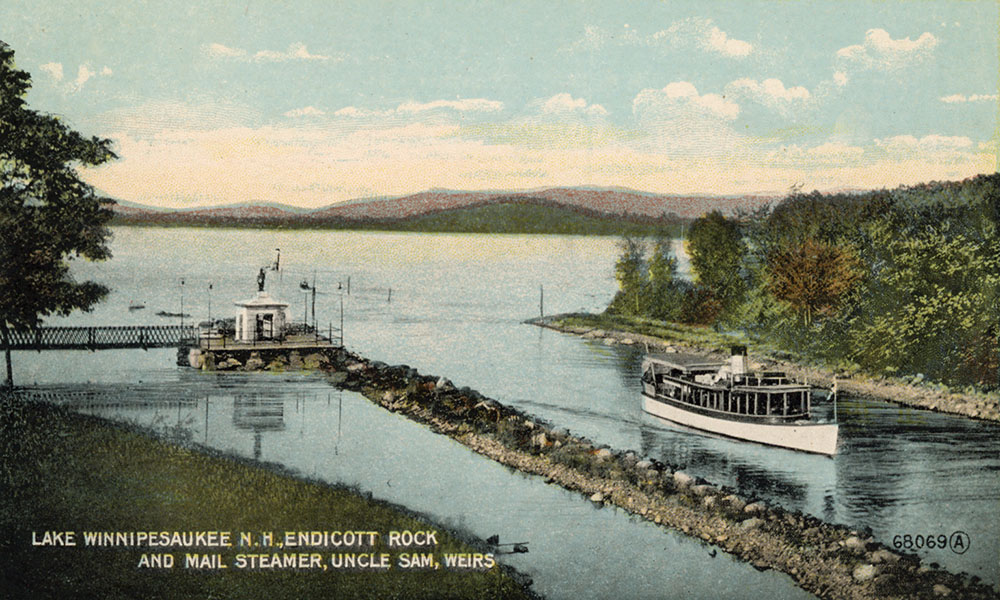

Endicott Rock was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. Click here to see a photo gallery of the Endicott Rock monument.

Endicott Rock & The Weirs Channel

In the autumn of 1650, the Reverend Gabriel Druillettes, a Jesuit missionary, became the first white man known to have visited Weirs Beach. In 1652 an expedition sent by the colonial Governor Endicott of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and guided by Native Americans Pontanham (“The Trapper”) and Ponbakin (“The Arrow Maker”), followed the Shad’s migration trail of water in reverse, discovering Lake Winnipesaukee upon arriving at Weirs Beach on August 1. Endicott Rock was then carved with the initials of the explorers to mark the northern boundary of the colony. The rock is still there today, protected by a monument dedicated on August 1, 1892.

Long forgotten, the rock was rediscovered in 1833 when the Weirs Channel was being dredged to allow the Lake’s first steamer, the Belknap, as well as other large craft, to pass between Lake Winnipesaukee and Paugus Bay. The steamer Belknap was 96′ long, had a beam of 17′, and a top speed of only 6 mph. It was so slow because it was so heavy, carrying a brick furnace around its crude boilers. The steamer had a nearly flat bottom with only a 4′ draft. This is what allowed it to pass through the Weirs Channel, which was still shallow after its first dredging. The steamer was primarily a freighter, and often pulled rafts of logs, further slowing the speed. She rarely carried passengers, thankfully. The steamer was extremely loud and could be heard from miles away. It wrecked on Steamboat Island in October, 1841. The name of the steamer probably came from Reverend Jeremy Belknap, of Dover, the “first historian of New Hampshire”. Belknap County was named in the Reverend’s honor in 1842.

In 1833 the channel was about twice as wide as its current width, but very shallow. Only the east side of the channel was dredged. Rather than being removed, the dredgings were dumped in the center of the channel, creating a barrier down its middle, with a deep, dredged eastern side, and a shallow, western side.

In his 1923 booklet “Ancient Aquadoctan”, Edgar H. Wilcomb wrote, “It should be borne in mind that the river channel in its natural state was unobstructed by the present central section of earth and that water flowed the whole width of the channel. To save time and expense in making the river navigable, only the east side of the channel was excavated, and the debris was thrown over towards the west side, where it still remains, practically an island or dividing mound through the center of what nature intended for a fine, wide passageway from the upper to to the lower lake. Since 1833, additional dredging has been done, at various times, on the east side, but the west side remains practically the same as in early days.”

To deepen the Channel, additional dredgings of the Channel occurred in 1846-1849, 1881, 1929, 1950, and 1952.

The 1846-1849 dredgings occurred when the Lake Company, which controlled the water rights to the Lake, dredged the Weirs Channel multiple times “in order to be able to draw Lake Winnipesaukee down by four to six feet lower than it previous lowest level”.

In the 1870s, a series of Rivers and Harbors Acts provided funding to the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to improve navigation nationwide. In 1880, USACE contracted with the Lake Company to remove 3000 cubic yards from the Channel to aid steamboat navigation on the lake. The dredgings were completed in 1881, but only 1540 cubic yards were removed.

An additional dredging occured in 1929. No further information is available about the 1929 dredging. Click here for info about the 1950s dredgings.

It was not until 1938 that the shallow western side was completely filled in to expand Endicott Rock Park, and the Weirs Channel became the narrow body of water with which we are familiar today.

Initially connected to land by a wooden bridge, a more substantial steel bridge connected the Endicott Rock monument from 1901 until 1938, when the part of the Weirs Channel separating the monument from land was finally filled in.

Circa 1908, the line of dredgings are seen at a very low lake water level. At high water, the dredgings could barely be seen. The Uncle Sam heads towards Paugus Bay.

Both of the color postcards below of Endicott Rock and the Weirs Channel were taken in the mid-1900’s. In the picture on the left, the level of the Lake is very low. In the picture on the right, the level of the Lake is very high, covering up the dredgings down the middle of the Weirs Channel, and almost submerging the monument. Notice the road on the right side of the channel. Today the road has been abandoned and the area is overgrown. The road was called Interlaken Avenue. Click here for extensive information regarding Interlaken Avenue and Park. In 2003, the City of Laconia traded its right-of-way to Interlaken Avenue for an easement to build a footbridge over the Weirs Channel. No such footbridge has been built.

Indian Trails and Water Routes

In 1652, when visited by the Endicott party, the village of Aquedoctan was fully occupied by several hundred villagers. Even after 1696, when the village was finally abandoned, when the small band left relocated to Pequaket (the Conway, NH – Fryeburg, ME area), Native Americans continued to sporadically visit the area to fish and hunt, as the white man had yet to arrive in any numbers.

Visitation was made easy by the several Indian trails that led from every direction to Weirs Beach. From the East, the Coheco-Winninanebiskek trail led from Dover Point to Alton Bay to Weirs Beach; from the South, the Merrimack-Winnipesaukee trail led from Pawtucket Falls in Lowell to Franklin to Weirs Beach; from the West, the Mascoma-Aquadoctan Trail led from the Mascoma River in Lebanon to Bristol to Meredith to Weirs Beach; and from the North, the Ossipee trail led from Ossipee Lake thru Sandwich and Moultonborough to Weirs Beach.

Besides the trails, there were several water routes to Weirs Beach. There was, of course, the southerly water route to Weirs Beach, following the Winnipesaukee River northward from its junction with the Merrimack in Franklin. Then, there was also an oft-used northerly water route to Weirs Beach. From the Pemigewasset river, the route was to canoe to Ashland, then up the Squam River, to Little Squam Lake, to the southeasterly arm of the larger Squam Lake. From there, there was a “carry”* of a half-mile to Wakondah Pond (Round Pond) in Moultonborough, a 1000-foot carry to Lake Kanasatka (Long Pond), and a final, 1/3-mile carry to Blackey Cove on Lake Winnipesaukee. These are no great distances to carry a canoe. Once on the lake, it was an easy paddle to Weirs Beach. The two ponds were renamed circa 1900 as part of a national renaming trend to replace common English place names with Native American ones. The English names, which appear on an 1885 Boston & Lowell Railroad lake map, were replaced by the native names on the USGS 1909 Winnipesaukee quadrangle map.

*Edgar H. Wilcomb described a “carry” as follows:

“In traversing the rivers with their canoes, the Indians found it necessary, as do their later-day brethren, to lift their canoes out of the water and “carry” them around the falls and dangerous rapids, so numerous in New Hampshire rivers and smaller streams. These places were and are still called “carrying-places”. The most frequently used Indian carrying-places in the lake region were at the Weirs, at Lakeport and at Laconia.

There are also numerous places of this kind across the “necks” of peninsulas extending into Lake Winnipesaukee, particularly across Moultonboro neck, which is nearly seven miles long. There are two or three of these old carrying-places across this neck, between Moultonboro Bay and the main body of the lake, still marked by the blackened soil of Indian campfires and remains of stone implements. Another notable carrying-place that has not changed much is upon Bear Island, at a narrow neck that nearly separates it into two islands. Finally, at the Long Island bridge, there was formerly another carry, before the level of the lake was raised several feet by artificial means.”

The First Settlers

The first white men to regularly visit the Weirs Beach area arrived in 1736, with the construction of a fort on the East bank of the Weirs Channel. This marked the definitive end of the era of Native American habitation of Weirs Beach. Eventually, the Natives withdrew, died out or were driven out of New Hampshire entirely. Today, New Hampshire is one of only 10 states nationally, and the only one in New England, with neither federally-recognized nor state-recognized tribal entities.

It was not until the 1760’s that white settlement really began to take hold in Weirs Beach, with the arrival of the first farmers and millers, which only began to take place once clear titles to the land could be acquired.

A 1784 map shows that one of the first settlers in the area was the family of Jacob Eaton, whose name, displayed as the “Eatons” on the 1784 map, is positioned at the Weirs. Historian Solon B. Colby states, “Eaton started to build on Hilliard Road, near Pickerel Cove, in 1765. By September 28th, 1766, he had built a house, cleared three acres, and felled the trees on six additional acres. This was done on what was later the George Hilliard place.” According to historian D.H. Hurd, the first birth among the early settlers was Eatons’ daughter Tamar, on March 11, 1767. A few months later, the second birth was the first son, Daniel Smith, born on July 4, 1767, to parents Ebenezer and Sarah Smith.

For the next 100 years or so, Weirs Beach was a sleepy little agricultural town, very little known by the outside world. But that was all about to change in a very big way. The arrival of the steamboats, the railroad, the Civil War veterans, and the Methodists, would soon speed the town’s transformation into a renowned tourist magnet.

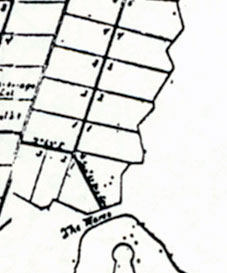

A detail from the 1753 “Plan of Meredith” map by surveyor Jonathan Longfellow shows the land of Weirs Beach had been subdivided but not sold.

By 1770, as this detail from the 1770 plan of Meredith by surveyors Ebenezer Smith and Josiah Sanborn shows, there were four original “proprietors” for the land of Weirs Beach west of the Weirs Channel. Edgar H. Wilcomb, who printed this detail in his booklet “Rambles About the Weirs”, added the marking to the four waterfront lots as “Range of Weirs Lots”. They were also known as “Point Lots”. Each original plot of land was roughly 100 acres in size. While the names of the original landowners are written in, the original landowners rarely inhabited their own lots. They were land speculators. The lots were sold, subdivided, and resold until the orginal settlers of Weirs Beach moved in.

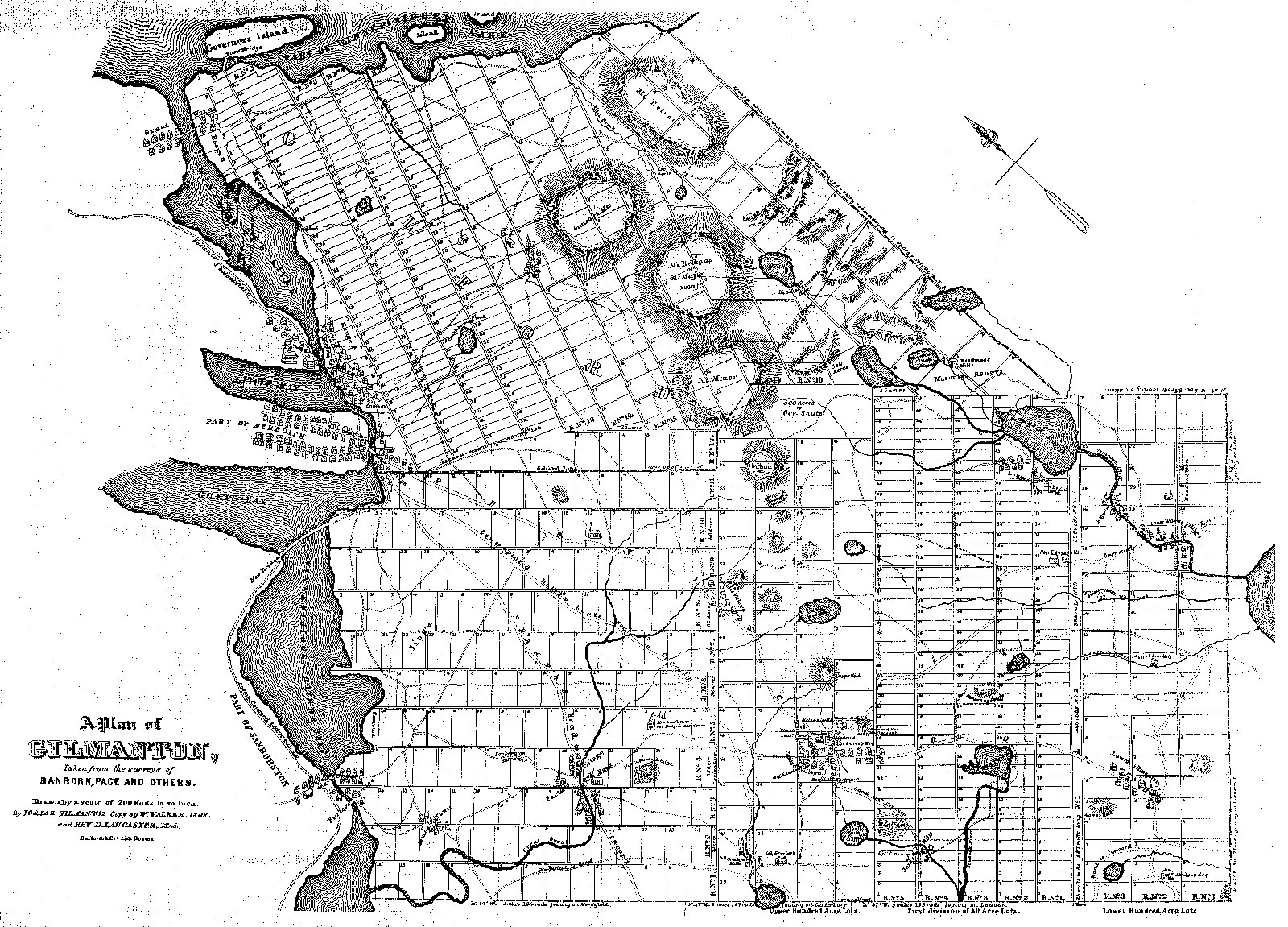

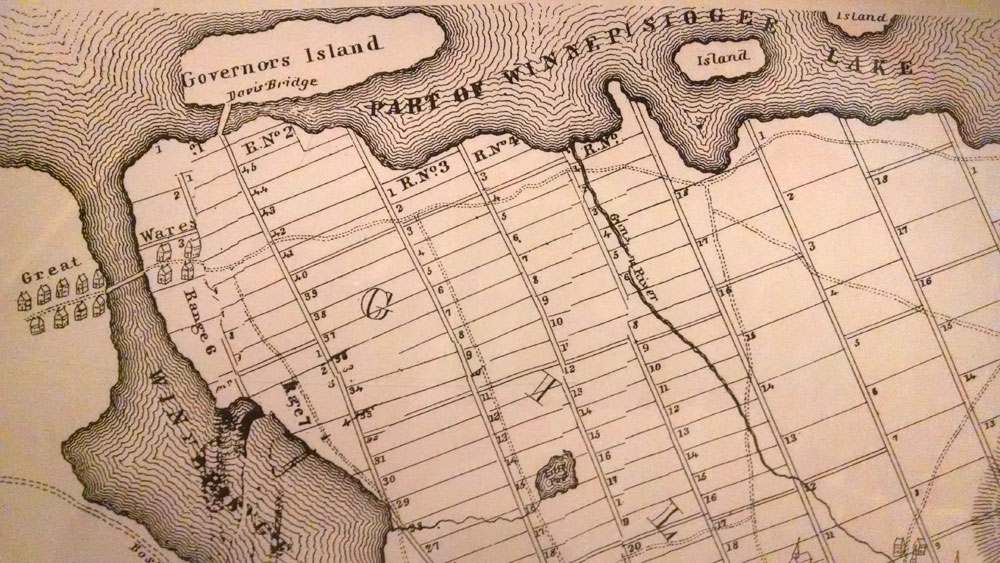

The detail below is from a map of Gilmanton drawn in 1772 by Josiah Gilman and revised in 1845. The revision overlaid the new roads, bridges, and houses extant in 1845 on top of the original, 1772 map. The map shows how the land was subdivided on the other, eastern side of the Weirs Channel. Weirs is called Great Wares. The channel and Paugus Bay is called the Winnepisiogee River. The planned route of the Boston, Concord, and Montreal RR is shown in the lower left, heading inland from Moulton Cove. The actual route as built in 1848 crossed Moulton cove on a bridge, and continued along the shoreline of the Lake towards Meredith.

The full size maps corresponding with the above map details.

![[Provincial and state papers]](https://weirsbeach.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/1753-map-edit.jpg)

![[Provincial and state papers]](https://weirsbeach.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/1770-map-edit.jpg)