Colonial Theater

Fire Curtain

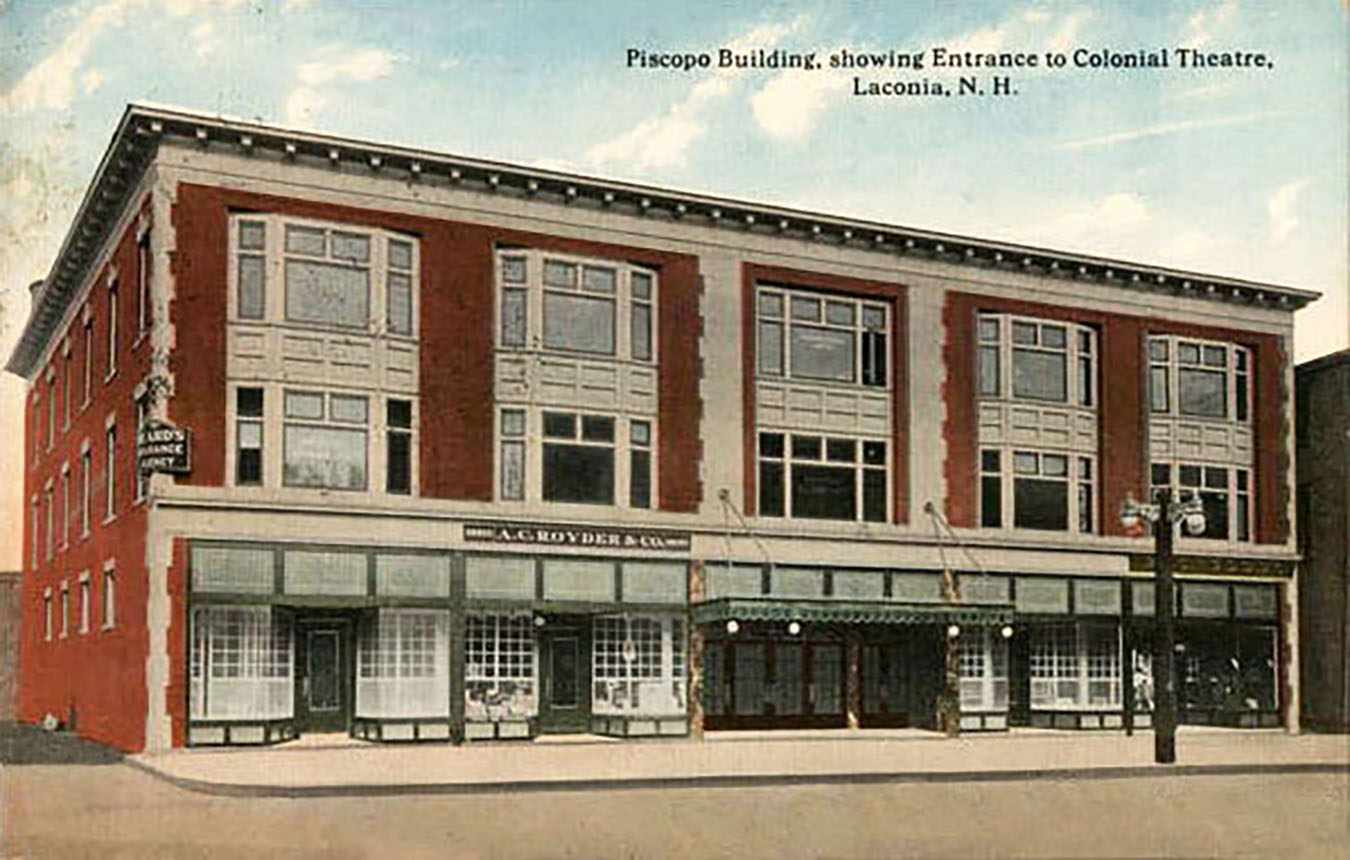

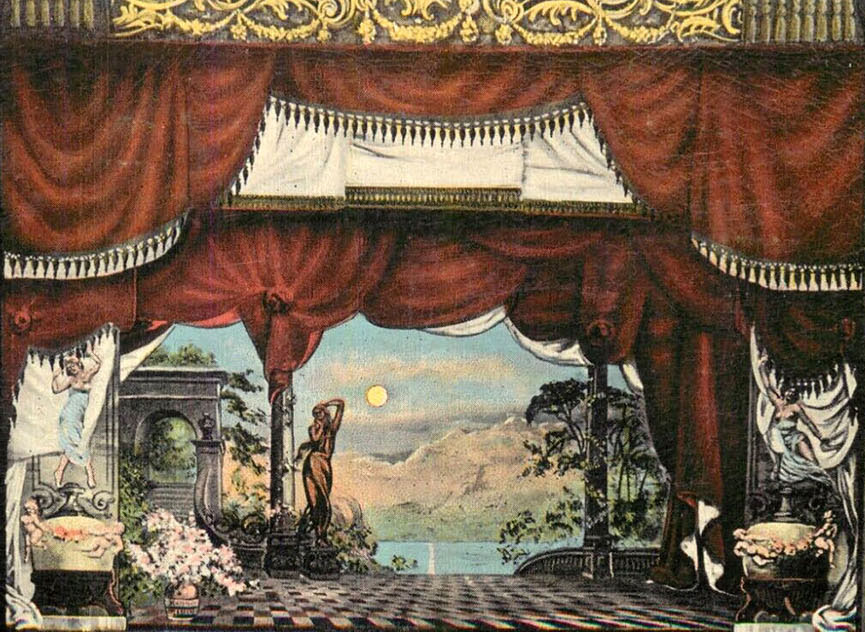

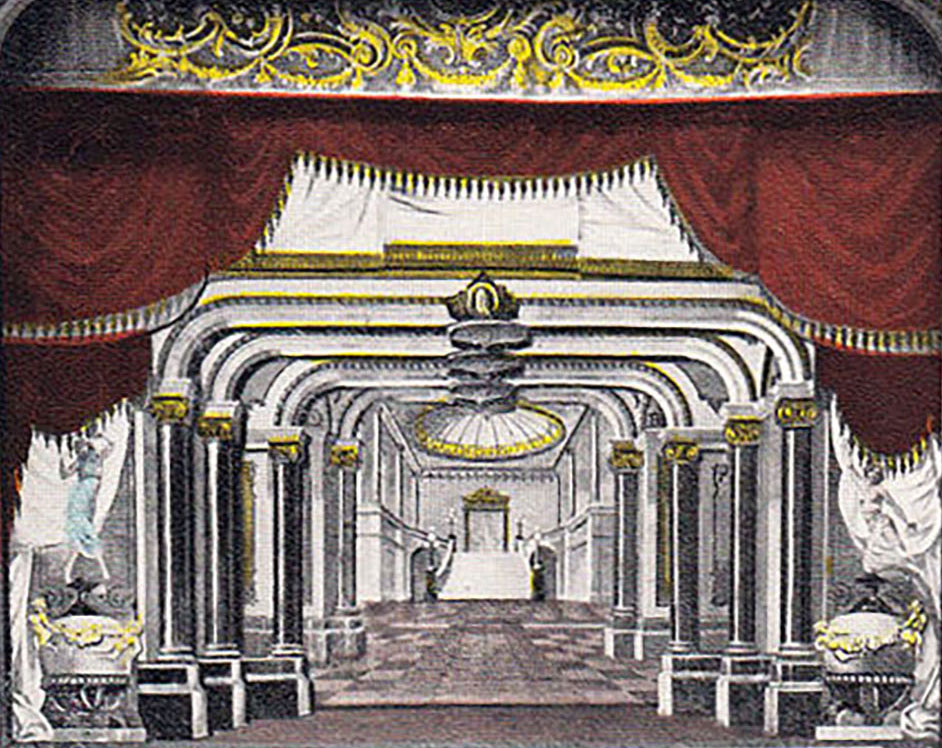

The Colonial Theater’s fire curtain depicted a tranquil scene of Venice. Benjamin Piscopo, who built the theater, was originally from Venice. He emigrated to Boston and became a successful real estate developer. Around 1911, he moved to Laconia and hired George L. Griffin, a local architect, to design the theater building, which was completed in 1914. The three murals adorning the plaster around the stage were painted by artist Peter Holdensen (1868-1952), who had a studio at 154 Boylston St. in Boston. Holdensen may have painted the fire curtain as well, but this is not certain.

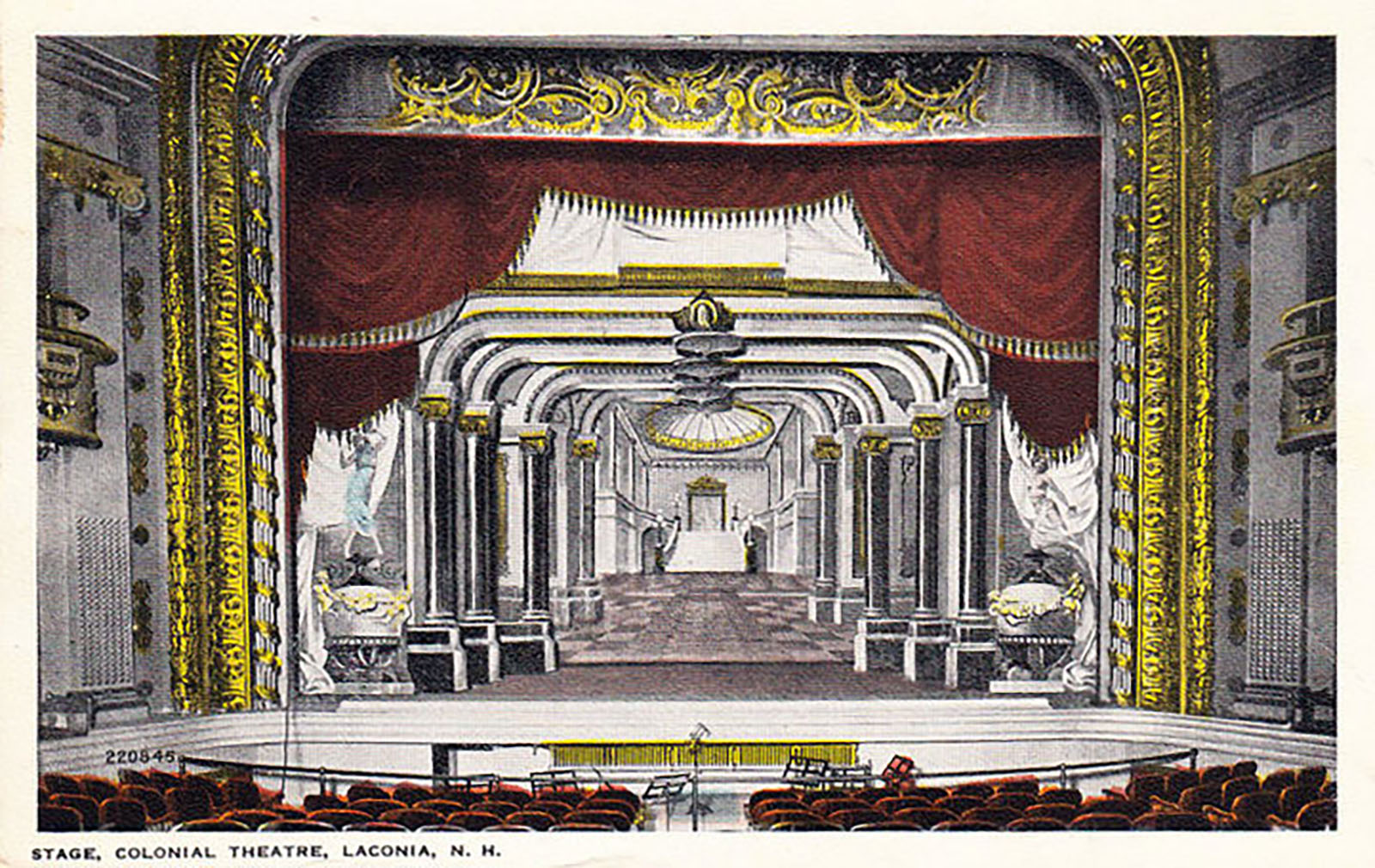

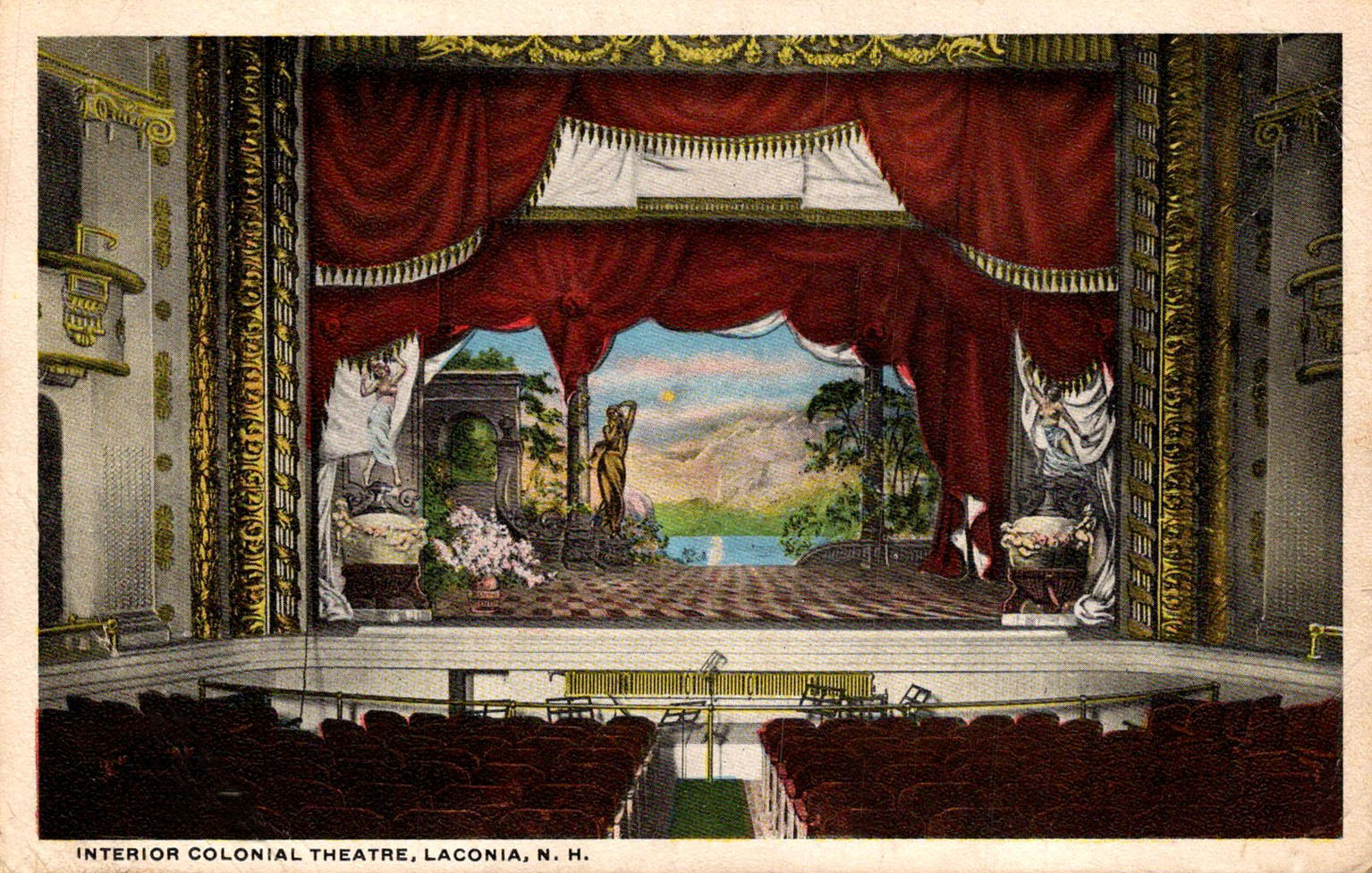

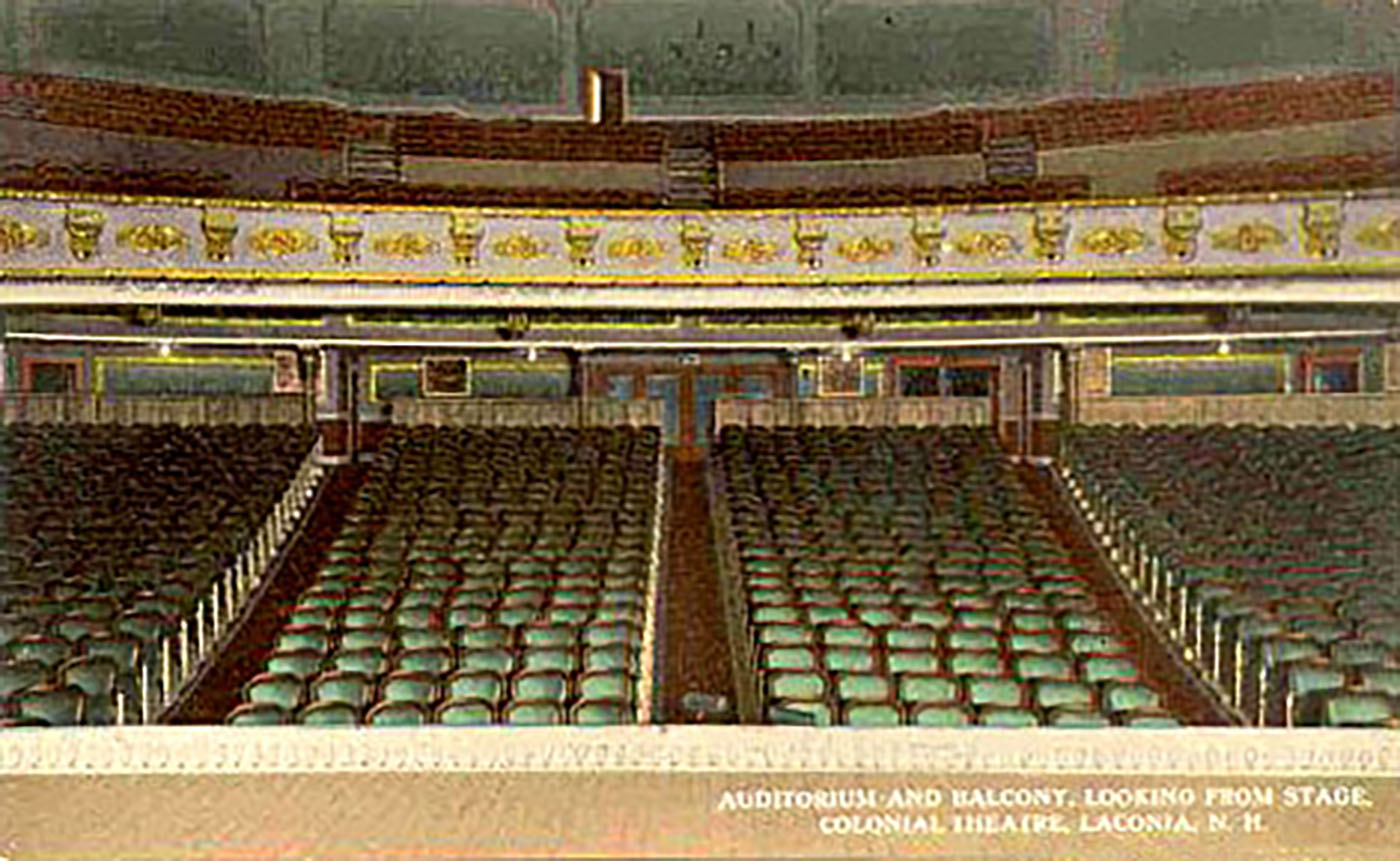

The Colonial Theater’s fire curtain was not the same type of curtain as its stage curtains, seen in the two postcard details below. The stage curtains would set the scene for various plays, and would be lowered for an intermission, and raised for the next act. The fire curtain was there to provide a barrier between backstage and the auditorium in case of a fire on stage, giving the audience extra time to evacuate. It was rolled up and stored over the proscenium, where it could be triggered by the stage manager pulling a lever or rope to drop it down into position in the case of an emergency. However, the fire curtain served a double purpose. The fire curtain could also be used to conceal the stage before and at the end of a theatrical production, so it was important to look good in addition to providing a fire barrier.

The Colonial’s fire curtain was discovered during renovations in 2019 when the ties keeping it rolled up released on their own. It then unrolled itself down from the rafters to the stage floor, providing a big surprise to the renovators. The curtain is made with asbestos, a known carcinogen, so it has carefully been stored away. It was manufactured in Boston by the Johns Mansville Company. The company was incorporated in 1901 and specialized in asbestos-related products.

What looks like curtains below are not actual curtains. They are painted on the stage curtain to make the background scene look further away and more dramatic. The painted-on curtains are the same on these two details, while the background scene changes. This suggests that these curtains may have been used for different acts of the same play.

“Stage curtains were made of cotton muslim and painted in watercolor to provide scene settings for theatricals, to simulate folded draperies for formal functions, and to carry advertisements for local business sponsors. A group of painters specialized in this work, offering standard patterns such as simulated drapes or columns; street, country and other stock scenes; and advertisements incorporated as borders or as elements of the picture. Painters were also commissioned to produce scenes of local significance such as well-known landscapes or streetscapes. They worked from studios which were large enough to allow curtains from fifteen to twenty-five feet wide and from eight to twenty-one feet high to be painted. The heyday of the curtain painters was from the 1890s to the 1930s, after which blank movie screens took the place of stages in theatrical halls. When painted curtains went out of use, they were often rolled up and stored in an attic or the space under the stage. Historical societies restore and preserve these pieces of popular art, which were once familiar to everyone in town.”

Daniel Heyduk, Stories in the History of New Hampshire’s Lakes Region, pgs 216-218.

Moulton’s Opera House Curtain

Another local curtain of note was the stage curtain from Moulton’s Opera House. Discovered in a Pleasant Street barn, the curtain was restored in 2014 by Curtains Without Borders through a grant provided by the New Hampshire Council on the Arts. The curtain depicts “Morning on the Nile”. The original, black and white 1859 etching, by Belgian artist Jacob Jacobs, was recreated in color by Eugene Cramer of Columbus, SC in 1887, adding the picture frame and drapes on each side. The curtain measures 26′, 10″ by 20′ high, and is composed of eight medium-weight muslim panels.