Captain Jack Statue

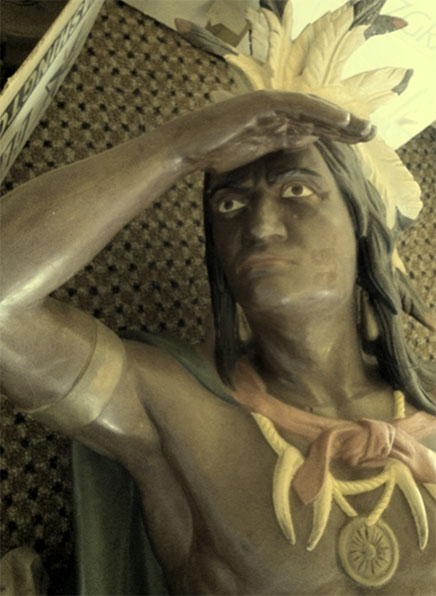

The Endicott Rock version of Captain Jack, now at the Laconia library

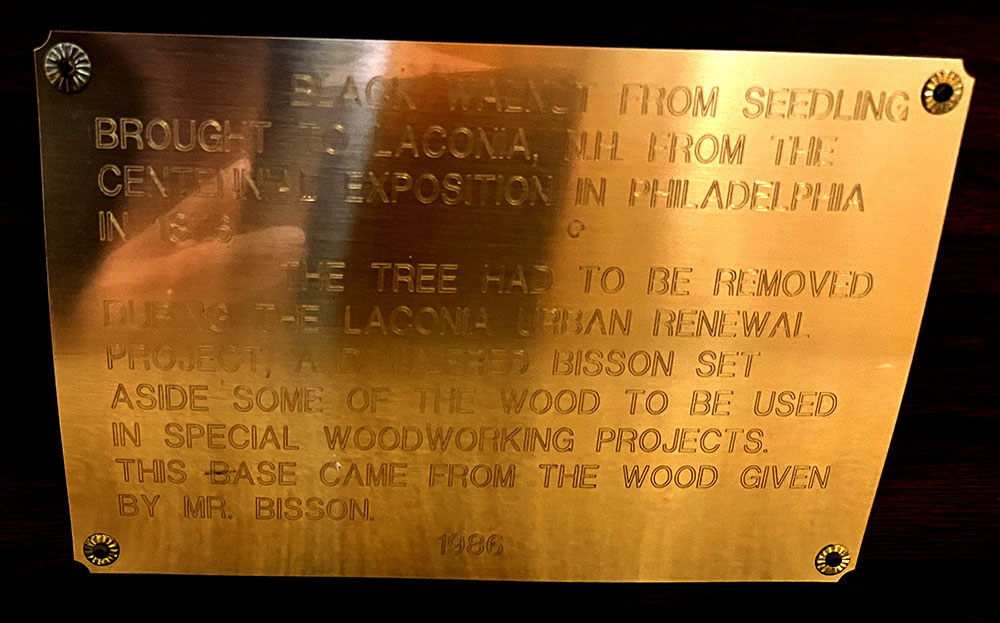

Plaques attached to the wooden base of the Captain Jack statue at the Laconia library

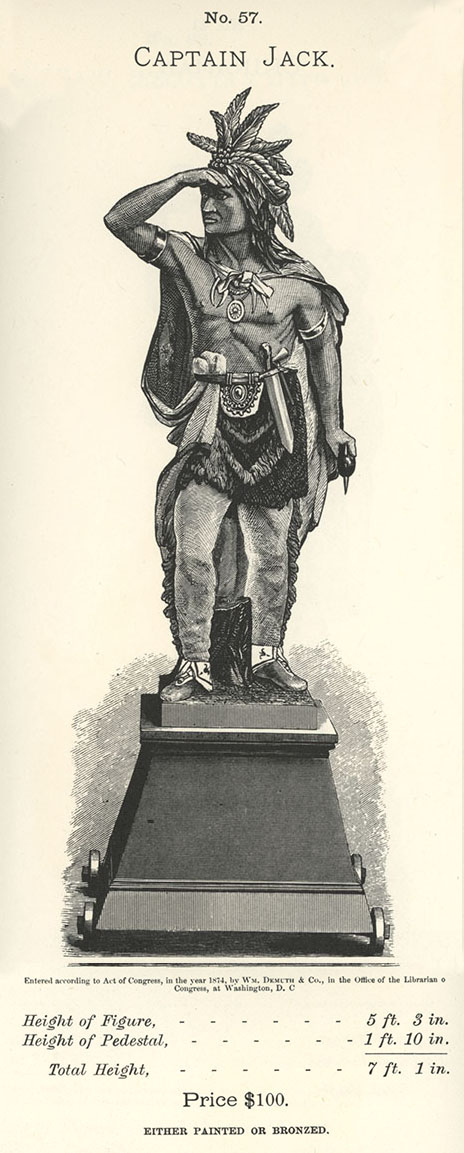

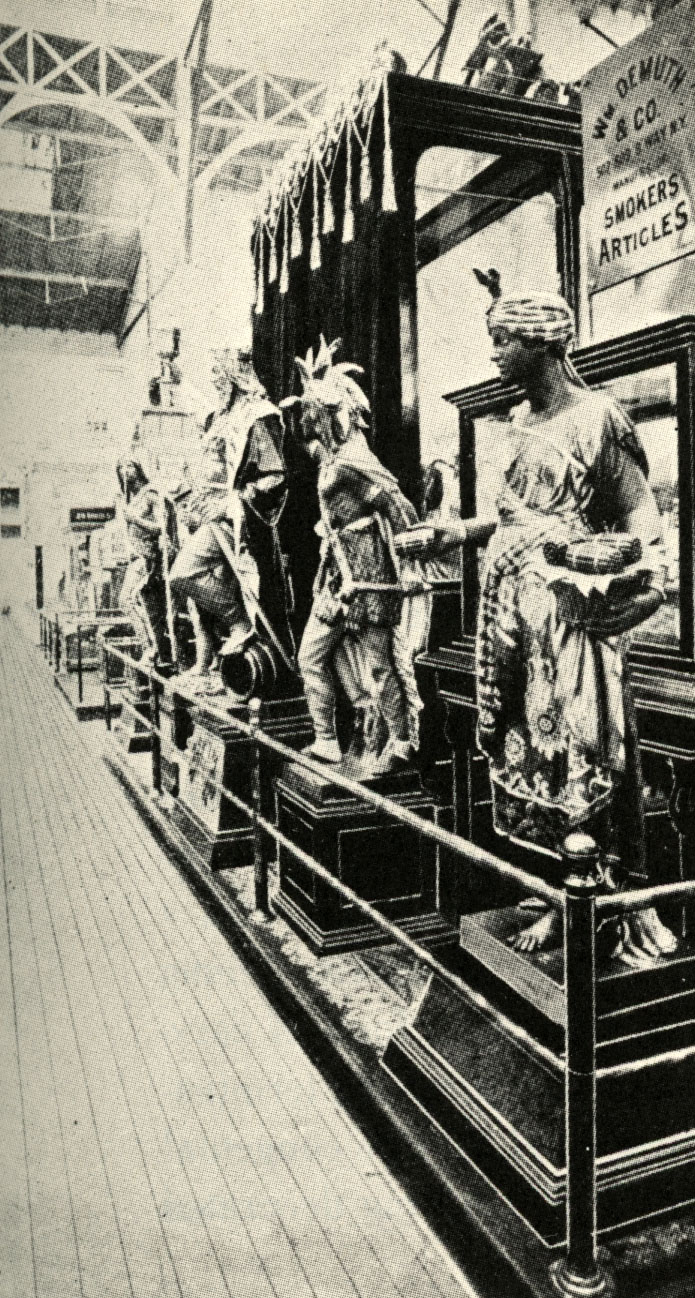

Captain Jack was a cigar store Indian manufactured by the William Demuth Company of New York City. Above is an engraving from the company’s “Illustrated Catalogue of Smokers’ Articles and Show Figures”. The catalog and all the items in it were submitted for copyright on August 21, 1875, which was granted.

While in 19th-century parlance these statues were called “show” figures, they did not appear in live performances; rather, they were shop figures, akin to a trade sign, and used to promote a variety of businesses. In an 1871 advertisement, Demuth stated, ”Before we commenced manufacturing Show Figures, their use was almost entirely confined to Tobacconists…now we are constantly manufacturing for all classes of business, such as Segar (Cigar) Stores, Wine & Liquors, Druggists, Yankee Notions, Umbrellas, Clothing, Tea Stores, Theatres, Gardens, Banks, Insurance Companies, etc…and to suit many other classes of trade…”.

In the original catalog illustrations, the show figures appear in reverse. The artists drew them normally on the engraving plate, but the resulting impression on paper displayed a reverse image of the original engraved composition. The webmaster has used the contemporary computer magic of Adobe Photoshop to flip the image of Captain Jack horizontally in order to show its true-life orientation.

According to Frederick Fried, author of “Artists in Wood – American Carvers of Cigar Store Indians, Show Figures, and Circus Wagons” (©1970, Crown Publishers Inc.), Captain Jack No. 53 was “…a smaller than life-size metal figure, in a popular pose, also made in wood in many variations of the same pose, and in larger sizes…”. The figure was based on a wood carving by Samuel Anderson Robb, a staff artist who worked for Demuth from 1864 until he opened up his own shop in 1876. The figure was cast at the foundry of Moritz J. Seelig in Williamsburgh, a neighborhood in Brooklyn. Seelig cast nearly all of Demuth’s zinc show figures.

Many copies of the Captain Jack statue are still extant. Unlike the Endicott Rock statue, these versions carry a war club instead of a tomahawk. Shown below are several of these. These copies were painted colorfully, to catch passerby’s eyes and lure them into the tobacco shop. However, the Endicott Rock copy was painted bronze, to emulate classical statuary. The Demuth catalog shows that the figure could be ordered either way. The tree stump at the base of the statue also contributed to its classical look.

Compared to wooden cigar store Indians, the advantages of the cast-metal figures were several: they could be left out in all kinds of weather; the paint, applied at the time of casting, lasted a long time; the metal would not check or crack in extreme temperatures; and their weight made the possibility of being carried off unlikely. However, the heavier weight could be also be a disadvantage, as the lighter weight, wooden Indian could more easily be carried inside and safely locked up for the night. Although the metal figures could be reproduced more quickly since they came from a mold, they cost more than a wooden version of the same design.

In 1886, when the Samuel A. Robb wood carving workshop was the largest in New York City, and probably the largest in the USA, the wooden cigar store Indian continued to be produced en masse. Robb stated; “For an ordinary six foot Indian, a foot per day is good carving, and painting and finishing runs at the same rate of speed, making twelve days in all. For the larger and elaborate figure, a month or more is occupied, according to the degree of finish required. The sizes run from eighteen inches high to eight feet. The price of these figures varies greatly. You can get a small Indian for $16, or you can indulge your artistic taste up to the tune of $125. Metal figures run up as high as $175. It is found that Indian figures are most in demand…Indian figures are divided into classes. An Indian with his hand shading his eyes is a “scout”. If he has a gun, or a bow and arrows in his hand, he is a “hunting chief”. If his head, except the scalp lock is shaved and the body partly naked, he is a “Captain Jack”…styles change, but the genuine old roving redskin with a bad eye and an ugly-looking tomahawk in his hand is the stand-by…”.

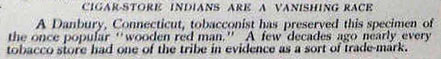

Of course, values today are way different, as the show figures have become rare, sought-after, valued folk art collectibles. The heyday of the figures, when they appeared on nearly every commercial street, extended from the 1850’s to the 1910s. They were done in by three factors: introduction of electrical signs, urban laws prohibiting sidewalk obstructions, and the need for scrap metal during WWI, when many a zinc figure was tossed into the scrap wagon. From perhaps over 100,000 figures there are only a few thousand left today. According to Mark Goldman, a New York City dealer in cigar store Indians, a full-size, zinc Captain Jack statue in good condition is worth $35,000 – $45,000 today.

What is the origin of the name Captain Jack?

Captain Jack was the mythical colonial hero of many adventure stories and dime novels which stirred the imagination of American youth during the 1800s. The basic story is that, during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), he was a white settler whose family was massacred by the Indians while he was away on a hunting trip. Swearing vengeance, he disguised himself as an Indian, and spent the rest of the war protecting other settlers whilst wreaking revenge on the natives. The first published version of his exploits, in 1829, was followed by another in 1843. In 1873, Charles McKnight wrote the most well-known version, “Old Fort Duquesne, or Captain Jack the Scout”. McKnight described Captain Jack as follows:

“The swarthy, sinewy, stern-looking man who sat at the rear (of the canoe), his paddle dipping idly in the water, and an earnest, almost wistful gaze thrown on either reach of shore, was the far-famed scout and Indian-killer, Captain Jack; as well known along the whole frontier line of Pennsylvania and Virginia, as was Major Washington himself. The mystery surrounding his origin and life, and the swart complexion which gave him the look and name of the Half-Indian, added to his fame. It was generally said he was a frontier settler who returned from a long day’s chase, only to find his cabin a ruin, and the butchered and scalped forms of those most dear to him, strewn around.

From that time, revenge became his all-absorbing passion, and hunting Indians his life-business, until he had become as much a terror to the savage tribes as a tower of strength to the white settler. He became noted for his reckless daring, his unerring aim, his skill in woodcraft, the sleuth-hound tenacity with which he could follow a trail, till it ended in the very camps of his hated foes.

His home was in the Juniata Valley, where even to this day a mountain bears his name, but his habitat was along the entire Susquehanna, from Fort Augusta to the Potomac.

In those cruel times of bloody warfare, when the pitiless tomahawk bore sway, he lived in many a fireside legend, and his name was potent enough to lull to sleep the restless infant in many a pioneer’s cabin. Innumerable were the tales related of the Black Rifle, the Black Hunter of the Forest, and the Wild Hunter of the Juniata — for by all those names was he called.”

Others have identified Captain Jack as a real person, an Indian trader named Jack Armstrong who was murdered by three Delaware Indians in 1744 during a trading deal gone bad. The incident was intensively investigated and reported. However, an article by Shirley A Wagoner in Pennsylvania History magazine, “Captain Jack—Man or Myth?” points out this would have been too early, as all other accounts place Captain Jack as active in the 1750s.

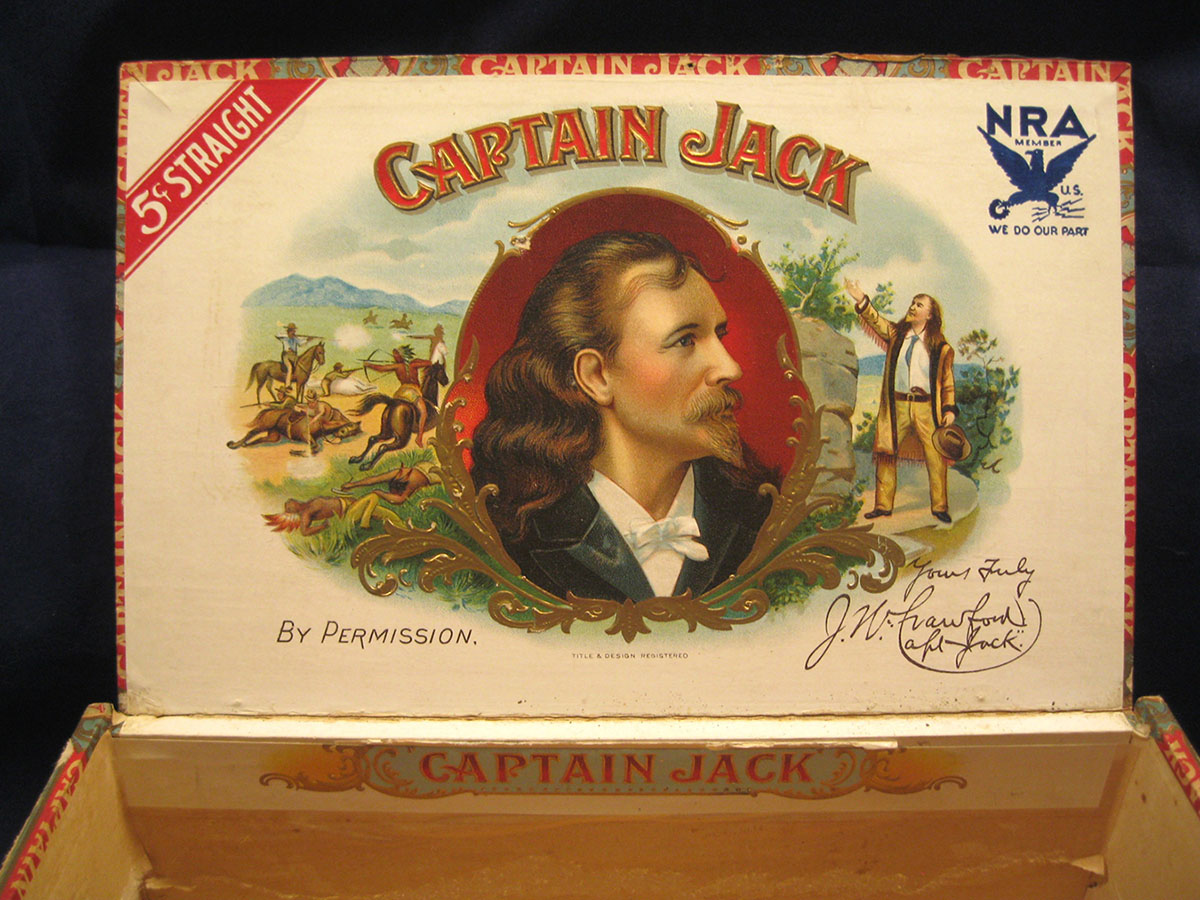

Captain Jack cigar box

The plaque on the Captain Jack statue at the Laconia library states that the statue “…served as the trademark of a famous tobacco company of the period.” Other sources have attributed the Captain Jack moniker to the Captain Jack Tobacco Company. The webmaster believes these are mistaken attributions; no such company seems to have existed.

There was a brand of cigar known as Captain Jack (see above), but the brand was based on a on a real person, a Western hero named “Captain Jack” Crawford. Similar to his earlier, mythical namesake, Crawford was once a scout assigned the responsibility of protecting settlers, in this case, in the Black Hills of South Dakota. After his military duties were over, Crawford joined his good friend Buffalo Bill in touring the country, performing on the stage in Western melodramas, his first claim to fame. Later, he became an author, poet, playwright, and lecturer.

Interestingly, there was another Captain Jack statue nearby, at Meredith’s Clough Park, from 1925 to circa 1950. Click on the Clough Park link for extensive information on the Meredith Captain Jack.

Below, photo and caption, “Cigar Store Indians are a Vanishing Race”. From a 1931 issue of the National Geographic magazine.